Earlier this month I promised some more posts on

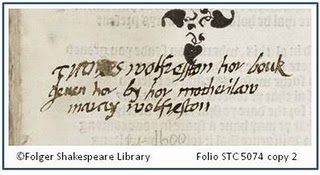

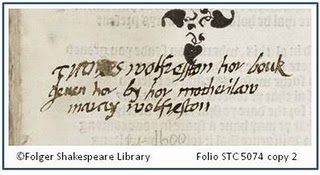

Frances Wolfreston and her copy of Chaucer’s works that we have at the Folger. It’s one of my favorite books at the moment, so there will be lots more coming, but here’s some starting information about Wolfreston’s books.

Frances Wolfreston (1607-1677) seems to have started collecting books after her marriage in 1631 to Francis Wolfreston (1612-1666)–or at least she started inscribing them after her marriage, since none of them appear with her maiden name, Frances Middlemore.* Nor are there any books inscribed by anyone else in the Wolfreston family prior to her marriage; in other words, she didn’t seem to sign books that were already in her husband’s collection, but built her own library of books.

Paul Morgan characterizes Wolfreston’s books as “the leisure reading of a literate lady in her country house.” They include plays and poems, but also jest-books and religious works.** Among the books bearing her signature are Heywood’s

Rape of Lucrece, Lodge’s

Wits Miserie, Ford’s

Love’s Sacrifice, Puttenham’s

Arte of English Poesie, Catholic and Anglican catechisms, many of John Taylor’s poems, and Shakespeare’s

Hamlet,

Othello,

Lear, and

Richard II. Most prominent among her collection is the surviving copy of the first printing of Shakespeare’s

Venus and Adonis, subsequently owned by Edmund Malone and now held at the Bodleian. (You can see an image of the title-page of that book

here, with her faint inscription just to the right of the printer’s device.)

Her books clearly were important to her, since she singled them out in her will with careful instruction about their care and use:

And I give my son Stanford all my phisicke bookes, and all my godly bookes, and all the rest conditionally if any of his brothers or sisters would have them any tyme to read, and when they have done they shall returne them to their places againe, and he shall carefully keepe them together.

Her collection of books, inscribed and passed on to Stanford, and then through his descendants, remained at Statfold House until they were auctioned off by Sotheby’s in 1856. A number of the books include not only her inscription, but those of her children and other family members. Taken together, Wolfreston’s collection can teach us not only about her own personal taste, but about books and social networks. Plus, there is a real thrill in seeing the signature of the same person over and over again–it’s a reminder that there are real readers who held and treasured these books that we now study. I’ll talk more about the collection’s integrity and the familial traces left in them in a future post.

*Not enough Francis/Frances names for you? Frances Wolfreston’s mother was Frances Middlemore, and the eldest son of Frances and Francis Wolfreston was, yes, Francis Wolfreston. Incidentally, Frances’s second son was named Middlemore (her maiden name), and the third son was named Stanfold (her mother’s maiden name).

**Much more information about Wolfreston can be found in Paul Morgan’s “Frances Wolfreston and ‘Hor Bouks’: A Seventeenth-Century Woman Book-Collector” The Library, 6th series XI (1989): 13-219. Especially notable is Morgan’s legwork in tracking down over one hundred books from Wolfreston’s collection; that list is included as an appendix to his article.

>I love your blog. Great combination of book history with contemporary reflection — just what an academic blog should be! I also appreciate the attention to questions of design. — Julia Lupton

>I agree, nice blog! It’s great to see some of these scans.