This week in class I showed my students (too briefly) one of my favorite books in the Folger’s collections, a 1483 printing by William Caxton of John Gower’s long poem Confessio amantis, written some hundred years earlier. I do not love this book because of its text—if I confess that I’ve never read the poem, will you hold it against me?—nor because of its author. I think it’s pretty cool that it was printed by Caxton, the man who established printing in England, and of course, there’s always kind of a thrill to any incunabula, but that’s not it either. No, I love this book because of the traces of its later owners, traces that interact with the text, traces that are all about the book but not the text, and traces that seem to have nothing to do with anything.

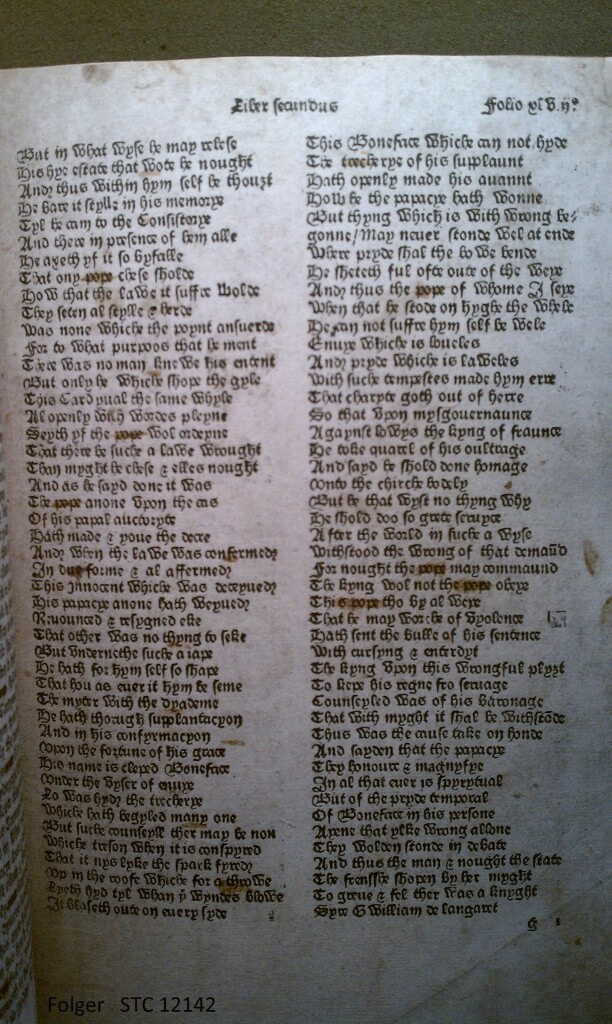

Here’s one set of marks that are fabulous: ((I apologize for the low quality of these photos; I snapped them with my cell phone when I was preparing for class, primarily for my own reference, but then I couldn’t resist the urge to share them!))

It’s a little hard to see what’s going on, so here’s a detail:

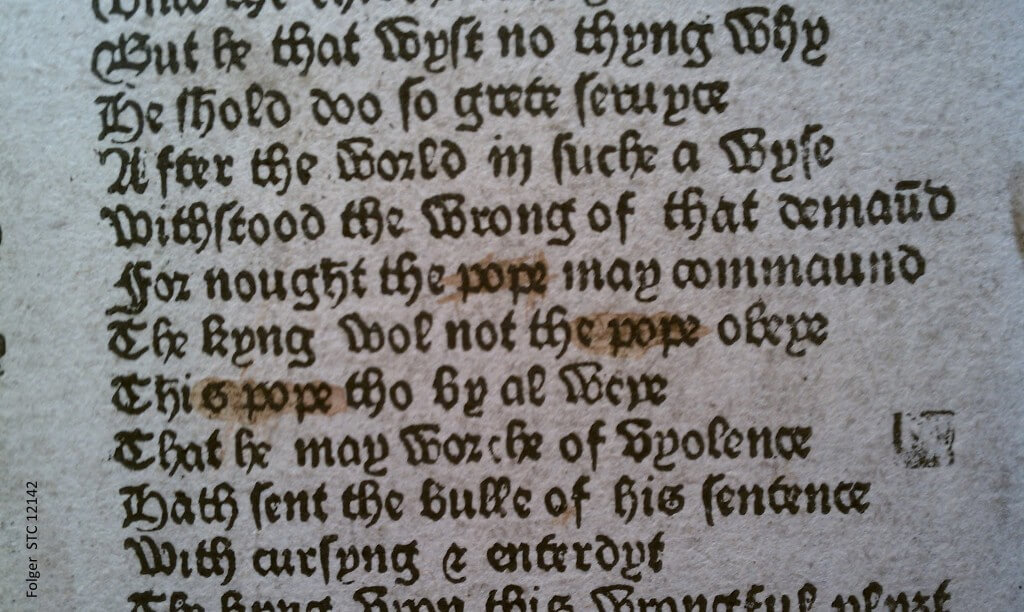

Do you see what the reader has done? The ink’s faded, but he or she has scribbled out “pope” everywhere it appears! Even better is the verso of this leaf:

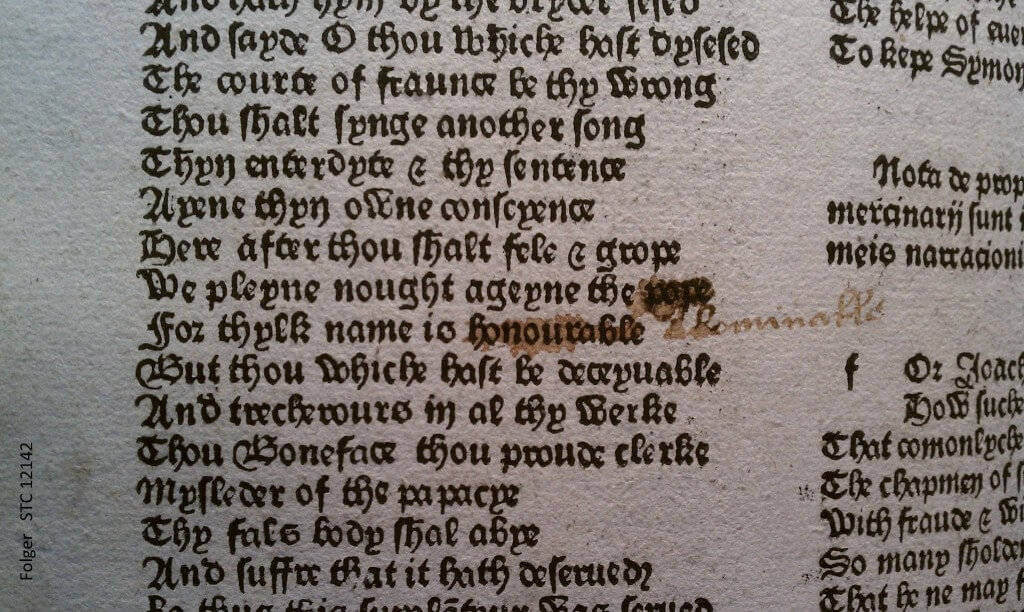

Not only has the reader crossed out “pope”, but he’s struck through “honourable” and replaced it with “abominable.” That’s some thought-out substitution—it keeps the rhyme and the meter (I’m assuming you’d elide the “i” to get four syllables). The final “e” on that “abominable” looks like the sort of two-stroke “e” that you see in mid-sixteenth century secretary hand. Though there isn’t enough for me to be able to date the annotation, you’ll see more in a moment that might give further clues.

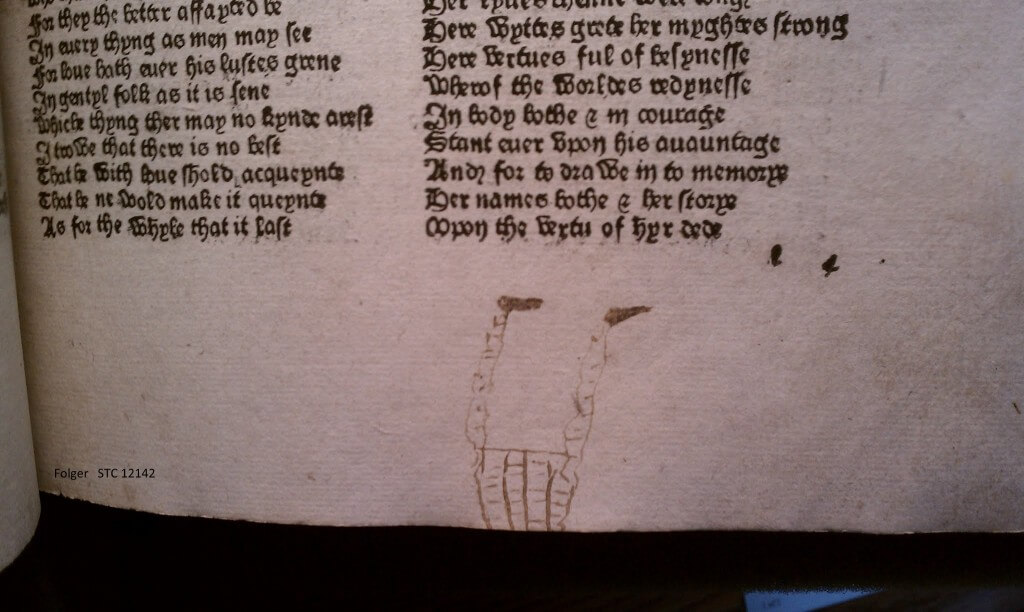

Not all the marginalia in this book is so attuned to the text. Other instances simply take the advantage of blank spaces in which to doodle:

As you know, I like blank spaces, and I like that page in the Gower because it shows how doodlers will need to use that space. I’m inclined to agree: if you’re not going to include nice initial letters or anything else deliberate in those spaces, really, something should be added.

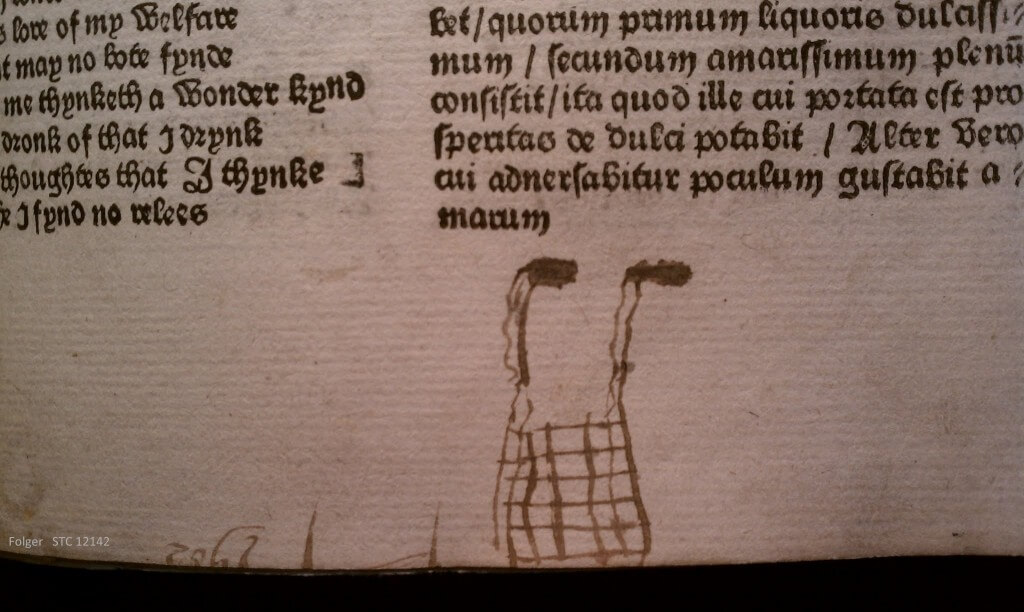

Blank margins at the bottom of the page are pretty tempting, too:

I suppose it’s possible that the bottom edge got trimmed during rebinding and that’s why this man has no head (or torso), but I’m not sure that’s what happened. Check out this guy:

There’s clearly some text that’s been trimmed, but I’m not convinced that even before trimming this guy had a head, poor thing.

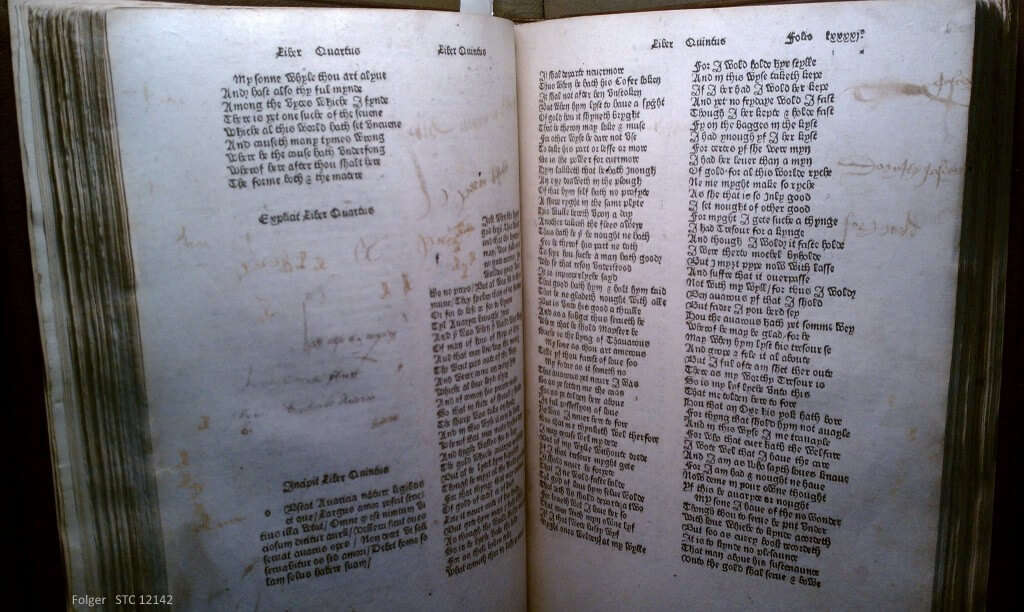

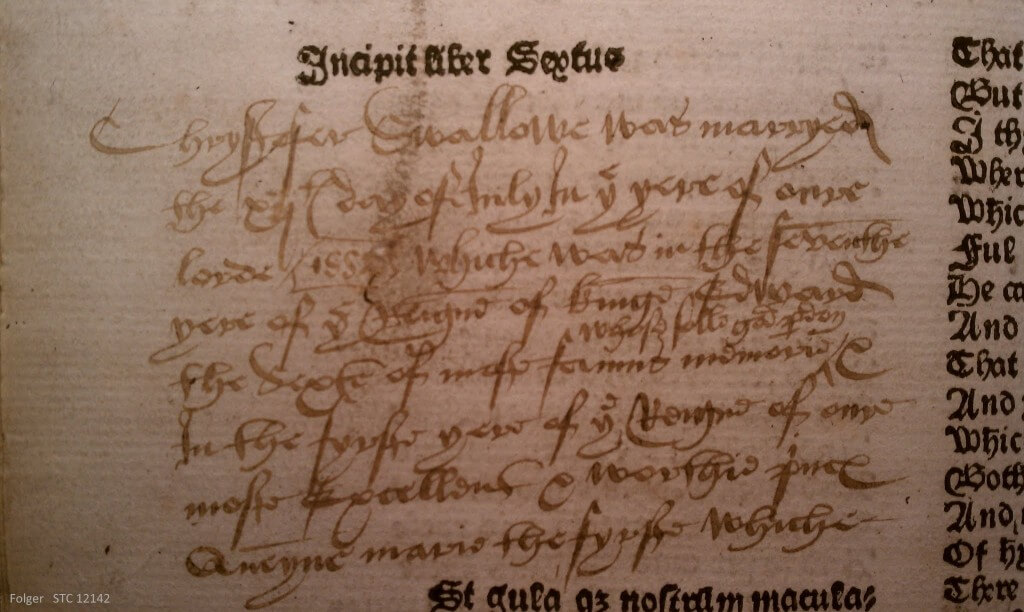

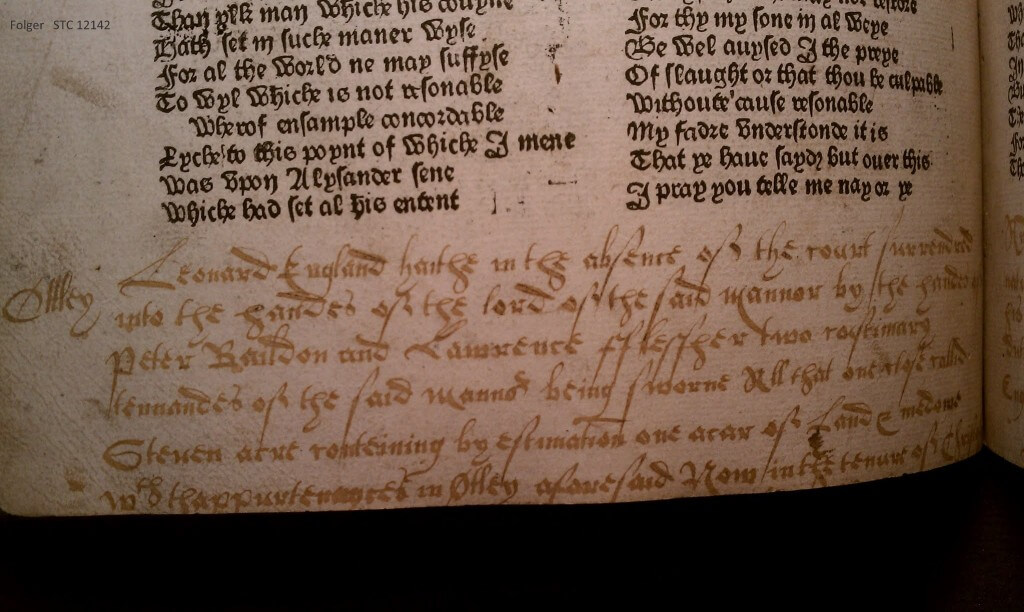

In any case, all that doodling is pretty great, I think, but the blank spaces of the book have also been used much more intentionally:

That’s just one piece of a series of notes giving information about Christofer Swallowe, this one dating his marriage, and others naming his children. But as fabulous as that is, it’s not my favorite bit of marginalia. This is:

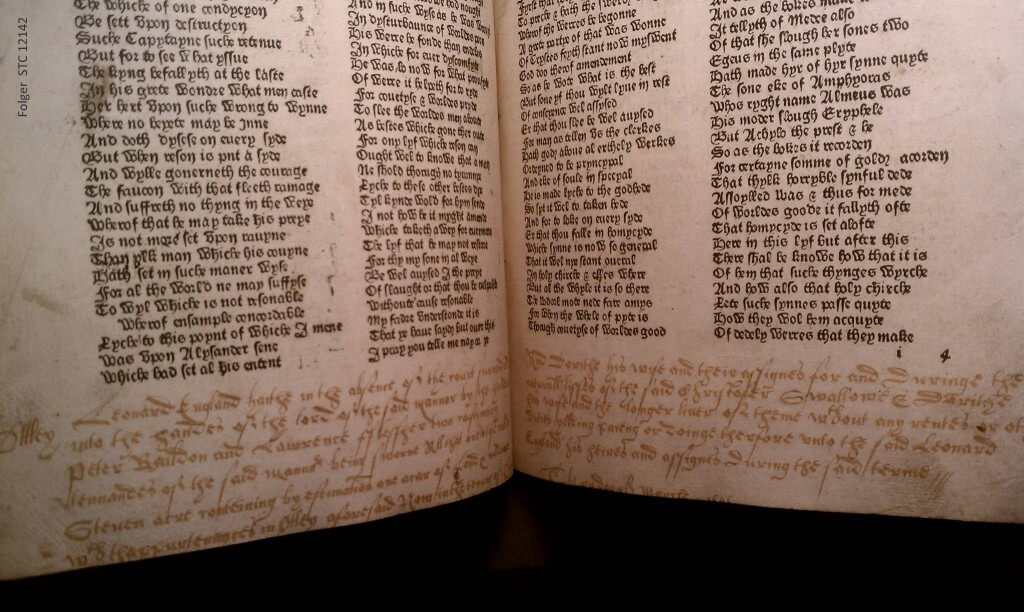

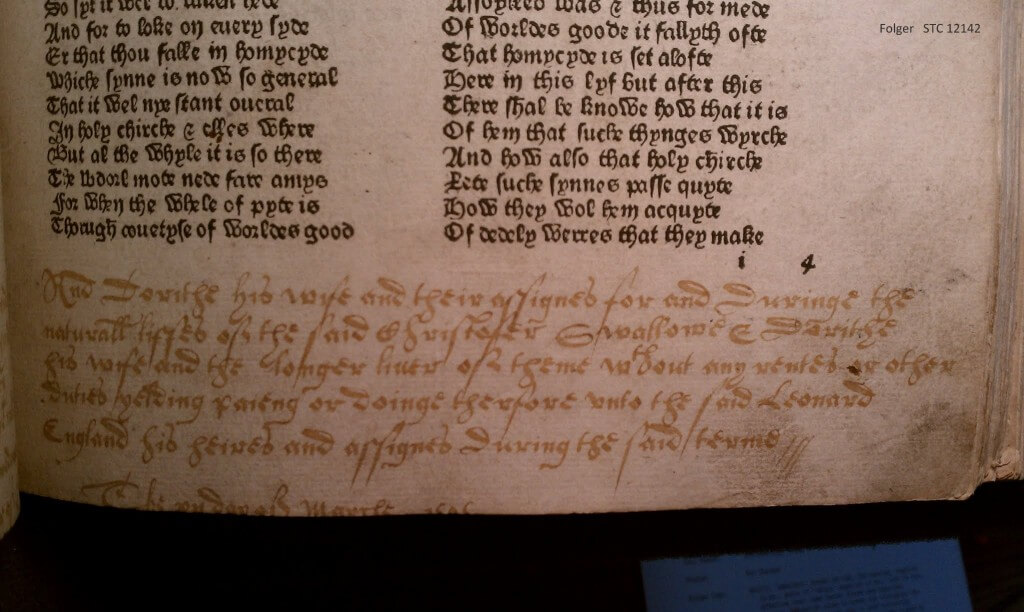

It’s hard to read, so here’s a close-up of each page:

And here’s an attempt at a transcription:

Ottley Leonard England haithe in the absence of the court surrendered into the handes of the lord of the said manner by the handes of Peter Baildon and Lawrence fflessher two c[o]stimary tennandes of the said manner being sworne All that one close callid Steren acre conteining by estimation one acar of Land & medowe with thappurte[…]es in Ottley aforesaid Now in the tenure of Christofer

And Dorithe his wife and their assigned for Duringe the naturall liffes of the said Christofer Swallowe & Dorithe his wife and the longer liuer of theme without any rentes or other duties yelding paieng or doinge therefore unto the said Leornard England his heires and assigned During the said terme /// The xii day of Marche 1[…] {lost to trimmed bottom edge}

Isn’t that wonderful? A deed! Recorded in the margins of Gower’s Confessio amantis! It’s got nothing to do with the text and everything to do with the fact that this is a big book with white spaces to spare: there’s room for the information to be copied and security that the book isn’t going to be misplaced or accidentally thrown out with the rubbish. All these different types of writing in books and all in one book!

Changing “honourable” to “abominable” makes me wonder what sound replaced “pope” in the annotator’s mind. A raspberry would take too long for the metre (at least, I think it would: I’m not alone in the room, so this remains an untested theory) and the now-familiar “bleep” would be anachronistic.

That’s interesting. It hadn’t occurred to me that there might be a replacement word/sound for “pope”–I was just seeing it as obliteration and assuming that’s how I was intended to see it. But the replacement of “honourable” does suggest that maybe something else should be filled in for “pope.” I think you should find an empty room and report back on your discoveries!

Wow, these are amazing! I’m a marginalia fiend too, and these are just brilliant – and cover so many different reasons for it in the one book. Thanks for sharing this, I’m jealous.

I’ve seen some other marginalia that’s blacked out words and images – early censorship at work! Fortunately for the modern reader, the censoring ink fades far more readily than underlying print in almost every case.

What always gets me about marginalia is as much as I love to discover and discuss it, I hate to leave marginalia in books. It’s about all I can do to write my name on a flyleaf!