My last post focused on my frustration with the assumption that digitization is primarily about access to text:

But access is not all that digitization can do for us. Why should we limit ourselves to thinking about digital facsimiles as being akin to photographs? Why should we think about these artifacts in terms only of the texts they transmit? Let’s instead think about digitization as a new tool that can do things for us that we wouldn’t be able to see without it. Let’s use digitization not only to access text but to explore the physical artifact.

I spent the remainder of that post brainstorming some suggestions about what digitization might enable other than access to text, and there were some great comments about the ramifications of textualizing the digital that I’m still mulling over. In this post I want to offer some examples of why we might want to look at books rather than digital surrogates as a way of approaching the relationship between digital and physical from another angle. ((I don’t really like the opposition between digital and physical that this phrasing suggests, as I’ve written about before, but since it’s hard to find another formulation, I’m going to stick with it for now.))

So why might we want to look at physical books rather than digital surrogates, other than a fetish of smell and a sense of the magical presence of the original? Here are a few examples that start to get at what physical books offer that digital surrogates miss.

The making of the book

One of the things that we learn from examining books is how they are made. There are all sorts of things you can see in physical books that reveal their making: watermarks and chain lines in the paper (which can help date a book, as Carter Hailey has shown ((See his article in Shakespeare Quarterly (http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/shq/summary/v058/58.3hailey.html) or the open access, simplified version in the Folger Magazine (http://www.folger.edu/documents/FolgerMagazineCarterHailey.pdf).)) ); sewing structures in bindings (which can reveal if pages have been cut out or added in later); and pasted-in cancels or errata slips (which show changes made due to correct errors or in response to censorship).

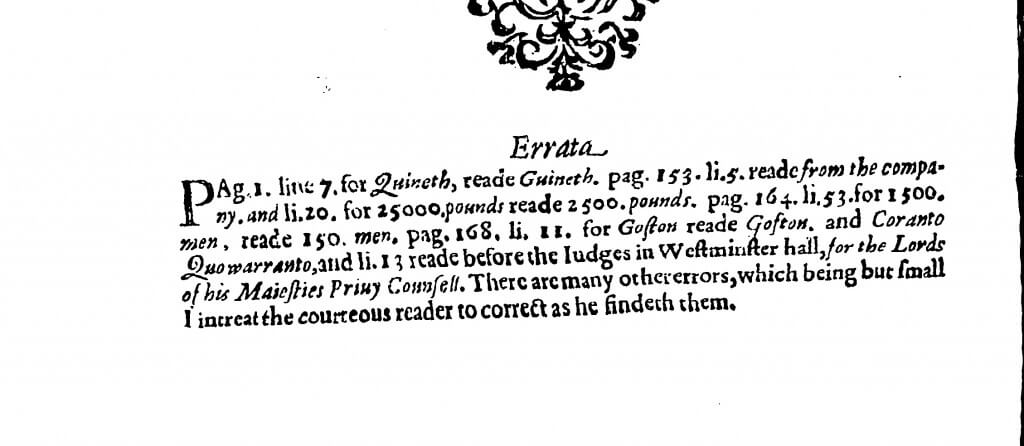

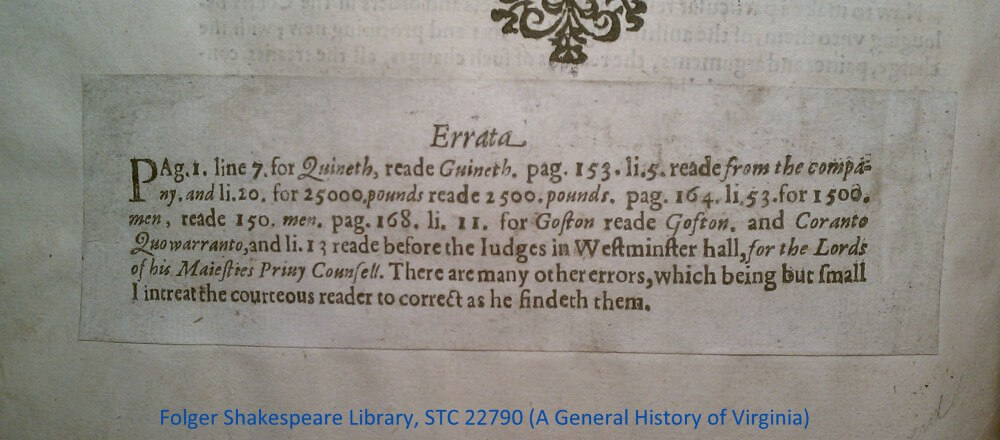

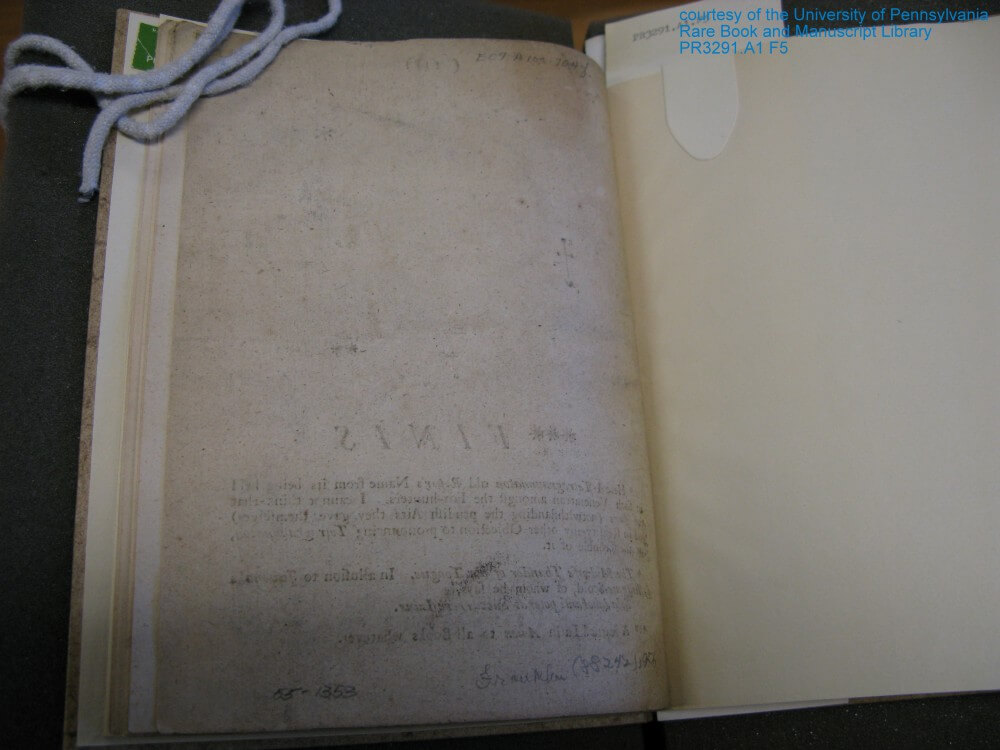

It’s true that some of these features could be incorporated into digital surrogates; as my photo above shows, it’s absolutely possible for digital images to reveal paste-ins such as this one. But it’s also true that most users of digital surrogates of early modern books rely on EEBO, in which the equivalent page appears thusly:

The text might be the same, but there is no indication in the EEBO reproduction that the text appears on a slip of paper that has been pasted onto the page (although a keen eye might notice that the lines are not quite square with the rest of the page). If all you care about is text, that’s fine, but you’re missing a key part of the book’s history. And what happens if you were looking at a copy that didn’t have the errata slip (not all copies did)? You might never know it was an option–see the later section, “a copy is not an edition” for more on that.

The text might be the same, but there is no indication in the EEBO reproduction that the text appears on a slip of paper that has been pasted onto the page (although a keen eye might notice that the lines are not quite square with the rest of the page). If all you care about is text, that’s fine, but you’re missing a key part of the book’s history. And what happens if you were looking at a copy that didn’t have the errata slip (not all copies did)? You might never know it was an option–see the later section, “a copy is not an edition” for more on that.

My larger point here is that while digitization could convey some aspects of this category of information, they generally do not.

The history of the book’s use

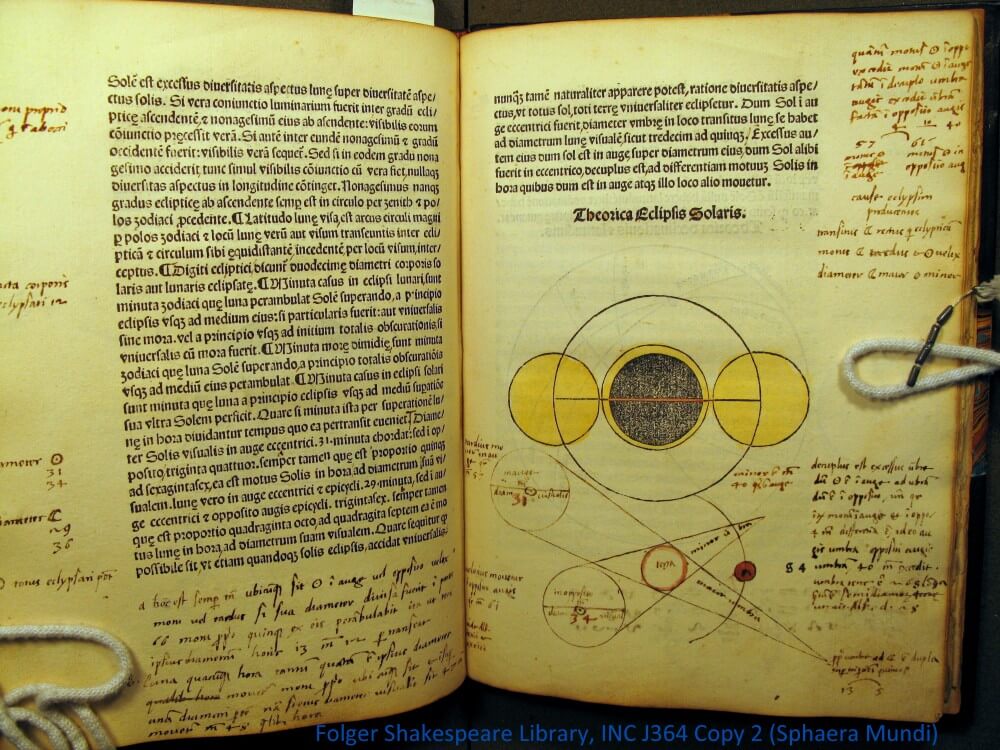

The best thing about old books, I think, is their longevity and the traces of the history that they carry with them. Inscriptions, marginalia, doodles, vandalism, erasures, cutting out images and leaves–none of those are captured if your focus is solely on the text, and all of them have something to tell us about how a book was used.

(This is an image of one of the Folger’s three copies of Sacro Bosco’s Sphaera Mundi; this one happens to be heavily marked up, with additional diagrams penned in and plenty of annotations, but the other two are significantly less annotated. It looks yellow, by the way, because I took the photo myself, sans flash, per Folger requirements. There’s not a whole lot of light in the Old Reading Room, and I did a sort of half-hearted job of color-correcting my picture.)

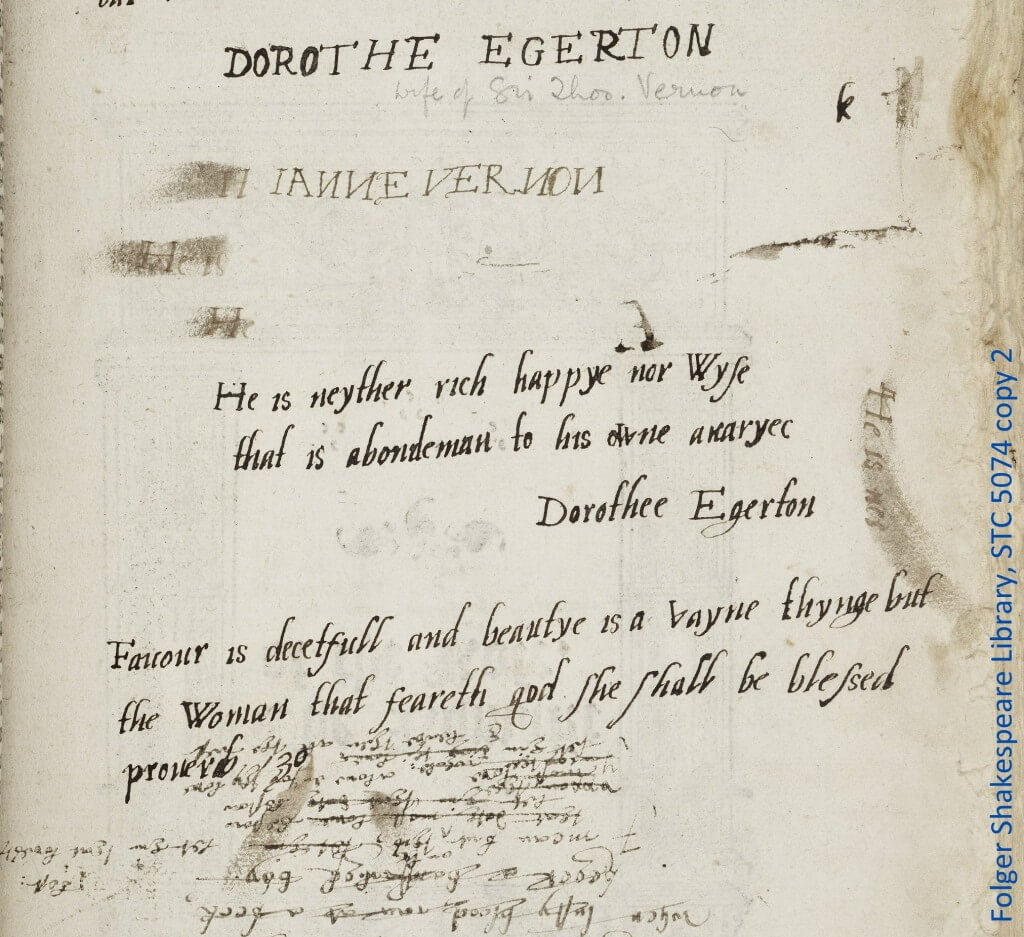

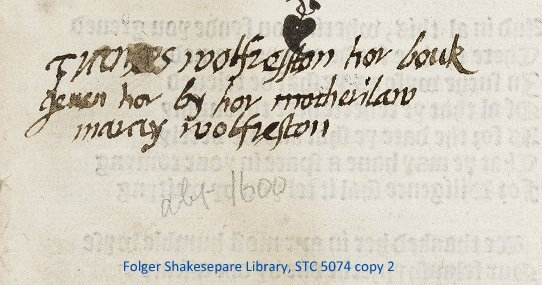

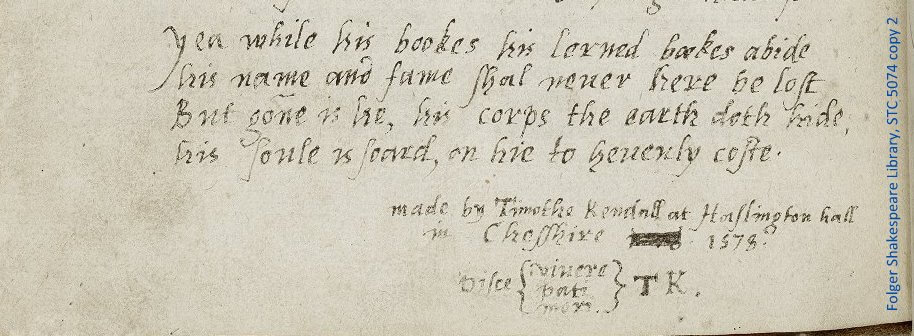

Here’s a detail from a blank leaf from the middle of a 1550 Chaucer Works that’s covered in marginalia. I count at least four hands in this picture, three sixteenth-century and one twentieth-century. There’s other marginalia in this book, too:

So add two more hands (this time a seventeenth-century and a twentieth-century one that is mistaken about the date) to the collection of readers who have left their traces in this book. And then there’s this, from the same volume:

So that’s one more inscriber (although he doesn’t appear to have been an owner of this book). There’s also the cover of the book, with two more names incorporated into the binding, eighteenth-century descendants of Frances Wolfreston. I’ve written about this book and this collector before, so I won’t go on further here. But this kind of passage through history tells us not only about one particular family and one particular book, but gives a window into different responses to and uses of Chaucer’s poetry. ((There’s a great piece by Alison Wiggins on marginalia in Chaucer that draws on some of the books at the Folger; “What Did Renaissance Readers Write in their Printed Copies of Chaucer?” The Library 9:1 (March 2008): 3-36.))

I suppose it’s possible that digitizing could capture this; if I can take pictures of these inscriptions, there’s no reason a digitization project couldn’t. Oh, except time and money. This is a big book of more than 300 pages, and only one of two copies we have of this imprint, and one of five copies of this edition, and one of I-don’t-know-how-many mid-sixteenth-century copies of Chaucer’s Works. Are we talking about a project that will digitize all pages, cover to cover, of all these books? Who’s going to fund that? Is it worth funding that as opposed to, say, funding digitizing all the books that were once owned by Ben Jonson?

The serendipity of finding the unexpected

This sounds a lot like the sort of paean to open stacks and browsing that you hear from some book fetishists. But I’m talking about something a bit more complicated, I think. When you look at a digital surrogate, someone has already made the decision for you about what you want to see and how you are going to use it. There’s no reason you can’t use the surrogate differently, but every choice they’ve made impacts your ability to circumvent it. For instance, some of the biggest digitization projects out there don’t include blank leaves or pages in their digitization. ECCO is the chief culprit that comes to mind: they prioritize text, and so their surrogates start with the frontispiece or title page, then move to the dedication/preface/letter to the reader/start of the text. But you know what’s missing? The blank verso of the title page. Does that matter? I don’t know. It might. It depends on what you’re looking for. But you’ll never know that you might be looking for an answer that depends on that blank presence if you don’t know that it’s not there.

Jeffrey Todd Knight has written about this serendipity in his most recent article, “Invisible Ink: A Note on Ghost Images in Early Modern Printed Books” ((Knight, Textual Cultures, 5:2 (Autumn 2010): 53-62; http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/textcult.5.2.53)). His focus is on ghost images left behind when some of the Pavier Quartos were bound together in early collections with non-Shakespearean works, so that an image of the title page of Heywood’s A Woman Killed with Kindness appears faintly on the verso of the last leaf of Henry V. Knight draws out some of the implications of what this means for the Pavier Quartos and our understanding of Shakespeare book history–go read the piece yourself–but he also makes a broader argument for the need to consider the invisible, reminding us that “it has been easy to forget that text reproduction technologies, at every level, carry biases”:

The onscreen interfaces that give us Shakespeare and Heywood’s plays today are not transparent windows onto the text themselves; they define and regulate a field of visibility, as do all forms of curation going back to the early copies, which also carried biases.

What I would emphasize is that we don’t know what we’re missing until it’s possible to see it. We can’t see the blank pages or the invisible ink if we’re experiencing a book through decisions that have already eliminated the possibility of seeing them.

A copy is not an edition

This is true for all books, but especially early modern books: no two copies are the same, whether through the process of how they were printed or their subsequent use by readers. The practice of stop-press changes ((These are usually called stop-press corrections, but as bibliographers will tell you, some of the changes are not corrections in the sense of fixing an error and it can be hard to tell which of two, or three, states is the first and which the latest.)) being made at any stage of production, and at multiple stages of production, and the habit of mixing sheets so that “uncorrected” sheets can appear in the same copy as “corrected” sheets, means that any book that had changes made during the printing process will exist in different states. Nor are those states typically indicated on a book’s title page or (depending on how important a book is seen as being and how well cataloged it has been) in its bibliographic record. You can only find these variants by looking at multiple copies of a single edition–hence the brilliance of things like the Hinman collator, the Lindstrand Comparator, the McLeod Portable Collator, and Hailey’s Comet, all devices that allow their user to compare multiple copies of books without actually reading them. (Reading, as any copy editor will tell you, will only distract you from what you’re actually seeing on teh page; collators–or, as I like to think of them, the original textual/machine hacks–let you look instead of read.) ((Interested in learning more about where you might see a collator in real life? Check out Steven Escar Smith’s “‘Armadillos of Invention’: A Census of Mechanical Collators” Studies in Bibliography 55 (2002): 133-70; http://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-sb?id=sibv055&images=bsuva/sb/images&data=/texts/english/bibliog/SB&tag=public&part=2&division=div))

Why do we care about these textual variants? We might care because they tell us something about how the book was made, because it might say something about economic or societal pressures (if they were changes introduced in response to something other than correcting an error), or because the presence of and differences between states might help us understand the range of textual meaning available.

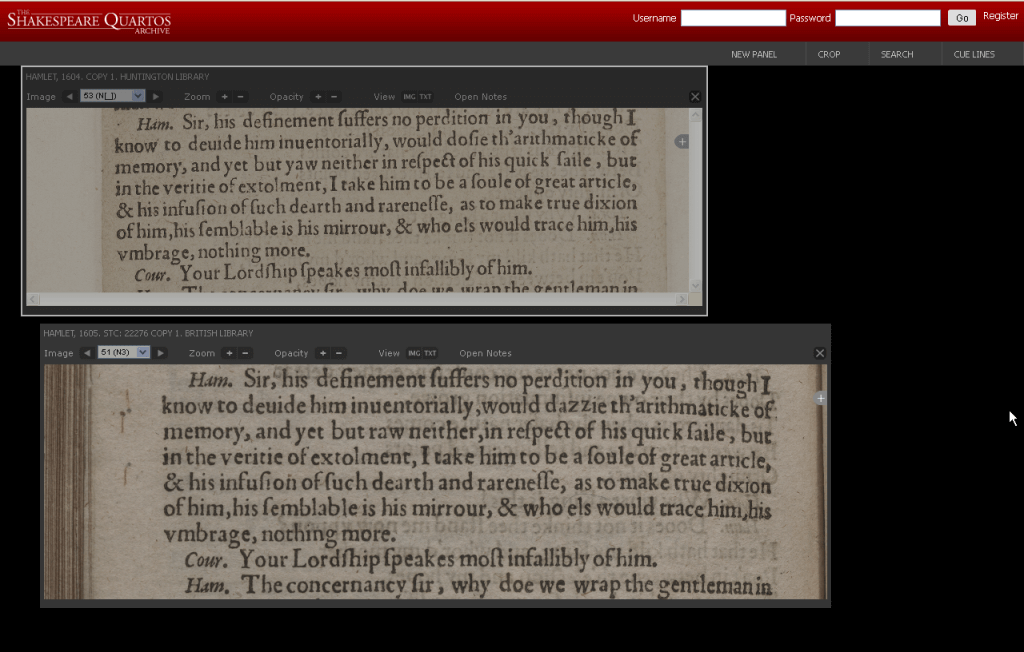

One example of the stop-press changes can be seen in the second quarto of Hamlet, in which Hamlet’s lines to Osric exist in three states, two of which can be compared in the Shakespeare Quartos Archive:

We are in no danger of missing the many textual variants of any of Shakespeare’s plays. But imagine if we were talking about, say, a Webster play, or a poem in praise of Queen Elizabeth. Those have not been as extensively, even fanatically, collated as Shakespeare’s works have. Nor have the funds been lavished on reproducing many digital surrogates of a single edition, as they have with Hamlet.

We are in no danger of missing the many textual variants of any of Shakespeare’s plays. But imagine if we were talking about, say, a Webster play, or a poem in praise of Queen Elizabeth. Those have not been as extensively, even fanatically, collated as Shakespeare’s works have. Nor have the funds been lavished on reproducing many digital surrogates of a single edition, as they have with Hamlet.

Remember above when I pointed out that some copies of The General History of Virginia have an errata slip, but others do not? If you encounter a digital surrogate of a copy that has the slip, you will treat that copy as if it represents the entire run of that edition, as if all copies of that edition of General History have errata slips. What is the characteristic of a single copy becomes a characteristic of the edition. But a copy is not an edition; what is unique to a copy is not common to the edition.

This list of possibilities has gone on long enough. Nearly everything I write about on this blog dwells on what we discover from looking at one copy of one book. If you’re curious to see more examples of what you might find from looking at physical books rather than digital surrogates, try some of the following posts in addition to the ones I link to above about blanks and Frances Wolfreston: “an armorial binding mystery“, focusing on overlapping book stamps; “essayes of a prentise“, about the significance of the binding on a volume of James I’s writings; “David and Goliath, redux“, about finding the same pattern of embroidered bindings; and “bibles for historical occasions“, in which I think about, um, bibles used on historical occasions.

I would love to hear more thoughts from you on this subject, particularly of lucid examples of what we can learn from looking at physical books beyond the sort of intangibility of emotions that books can evoke.

Great post Sarah, and I am still letting it ruminate, but a couple of points maybe to consider (love the gesture to Jeff Knight’s piece and the links to the collators!). First, it seems that the privileging (and I know you aren’t trying to grandly valuate) of the physical object over its “digital surrogate” only works at the user interface, at a certain level of knowledge on the part of the user. Matthew Kirschenbaum and others would have a better take on this, but treating a digital object with full biblio/(dato)graphic care would involve going “behind” that interface to the metadata or the code (digital objects are made as well). Once that is done, or as that is done, the “reader” reads the digital object in a very similar way to that of the book as object: i.e. someone viewing a digital reproduction without a little bit of DH expertise is like someone viewing a book without a little bit of BH/bibliography expertise. So, in a way, we are relying on “digitization to convey” certain elements that books themselves don’t generally to the reader non-conversant or interested in the bibliographic code. We have to improve our literacy with digital objects, be they digitized books or otherwise. Second, I wonder about your comment: “When you look at a digital surrogate, someone has already made the decision for you about what you want to see and how you are going to use it.” In perhaps a slightly more serendipitous way reception-wise and survival-wise, but probably similarly on the production side, this is absolutely true for books as well. Whether using model books from the Middle Ages for the format and design of incunabula and early printed books, or the capitalist conventions for trade publications and design structures that had been standardized during the Machine Press era…booksellers/financiers, political/social contexts, printers, (later) publishers, and even authors, made the decision about what they wanted the reader to see and how it was going to be used. Now, of course, as Bill Sherman (for EME) and others have admirably pointed out, readers worked against these prescriptions and used books in a myriad of unpredictable ways…but the same can be said for digital objects and texts, no? After all, what does hacking (rigorously defined) constitute?

PS. I don’t think this speaks to your major argumentative trajectory, and thus might actually be what you are saying in the large picture view (the perils of quick commenting).

I think you’re right that digital objects are made (as I’ve tried to talk about elsewhere) and that a naive use of digital surrogates is not super different than a naive use of books: to see what lies behind the surface requires knowing that there is a surface and that you can look beyond it. What I find frustrating is how little of the bibliographic knowledge of books is incorporated into the creation of digital surrogates and how often the digital is held up as an equivalent to the physical (even my use of the word “surrogate” suggests that). I’d rather have us think about one not as a replacement for the other (either books OR digital) but as supplements to each other. Each has their own biases. As I tried to suggest in the last post, there are things that the digital could offer that cannot be seen/explored/known with the physical. My point here is that the reverse is true as well.

But I do take your point that users must be educated to see the possibilities in what they encounter, whether it be book or digital. I’m not sure the need to increase our literacy is greater with the digital than with books–the digital is newer and therefore unfamiliar, but books are omnipresent and therefore overlooked.

(By the way, thanks for bringing Jeff Knight’s piece to my attention–it’s really fruitful, as you can see!)

I enjoyed this, and have some sympathy. But there’s a key word the first commenter used: privileged. You are very privileged to be able to see, to use these physical books. I sit here in England, and am not so privileged. There are billions others like me around the world who can never have that privilege. The digitised version may give less (in a way), but it gives it to more.

In the late 1990s, I first heard about a major digitisation effort, I think it was called making of America, based in Michigan. I seem to remember the premise was that the books to be digitised (destructively, if I remember) were selected partly on the criterion that they had not been touched for 25 years (candidates for de-accessioning). Sitting in my office in Warwick University, I had a look. I found one of those digitised books (through the truly terrible interface). For an afternoon I read, spellbound, a story of terrible hardship amongst some early American pioneers. I remember vividly the description of having to put the bodies of those who died outside in the snow, to be buried in the spring. This experience totally persuaded me of the value of digitisation. It doesn’t provide everything, but it gave enough for me.

I guess you’re not really saying digitisation is bad. You are saying the text alone is not enough. What I don’t think you said is “for whom”. I’m reading David Copperfield in a modern, scholarly, corrected paperback edition. It’s enough for me; I’m “the public” as far as this book is concerned. I’m not a Dickens scholar. For that scholar, the originals are essential, and no doubt (for reasons you explain) as many originals as possible, in case they reveal some extra facet. But most of us are interested in “the work” in FRBR terms, and by and large, I think this means the text, or something just above the text, what I think of as the story.

This doesn’t cover of course the other kinds of reading that are possible with digitised books, analyses capable of producing their own insights not attainable from the physical pages alone.

Anyway, this is probably just to say, you’re right. Digitisation is not enough, for everybody. But it’s potentially wonderful and liberating, for nearly all of us. But thanks for the great piece.

Sorry, I hadn’t read your previous post before commenting. But surely the answer is “not only, but also”?

Yes, that’s it exactly! It’s not either/or, but both for different needs. As you saw from my previous post, I do think that there’s much that digitization can do that is BETTER than what books can do–and access is a huge part of that, though it’s not what I focus on here or in that post. (And thanks for your anecdote about encountering that pioneer work through its digitization; it’s great to remember that serendipity can be built into digitization projects.) My point here is the reverse is true, too: there’s much that the physical book can do that is better than what digitization can offer.

I’m still stuck on the “fetish” business. Sorry, I know it is a very general concern and peripheral to your main points in this excellent post, but the derogatory tone when the term comes into play continues to bother me. Is someone who “fetishizes” printed, bound books different from a person who feels reverence for what they are and what they represent without having a specialist’s knowledge? And is this a degraded perversion? I don’t see it. Might we not say that the specialist “fetishizes” the errata and marginalia of the variant copies? I see this word as a complete red herring in the discussion.

Love your photographs, by the way. They add considerably to the interesting points you make.

I’ve got another post brewing that I hope will respond to some of this. The use of fetish is loaded and odd, undoubtedly exactly why Gleick uses it in his piece. I suspect it might have to do with what you started to suggest in your comment on the previous post, that there’s something to be considered in the machine-human interface that shapes how we respond to these questions. (And then I can get back to posting more book pictures!)

I love the book pictures, Sarah!

As an artifact of the human condition, there are, obviously, many ways to interpret a book.

On one level a book can be interpreted through its form. Bindings. Covers. Typography. Pages. Layout. Etc. It is also possible to interpret a book according to its context. When was it created? What other things were created in a similar vein or at the same time. We can also consider a book completely aside from its container and to its content. What does the book say? What is being expressed? It is in this later vein I think lies the most promise for digitization. Through digitization new interpretations can be garnered from a book much more easily than in its analog form. Through digitization (and optical character recognition) a person can begin to apply more systematic analysis against a text. Exactly how long is the book? What words were used more frequently or less frequently than others. Are their significant differences in the types of words/phrases used? What named entities exist in the text and can they be plotted on a map? What common themes are expressed, and can they be charted and graphed in order to illustrate their importance. Can these sorts of analysis be applied across an entire corpus? Sure they can, and they can be done at scale compared to the time of an individual reader.

Digitization of books offers a wide and varied set of tools for literary analysis, no mater if the analysis is about a book’s physical manifestation or its inherent message.

—

Eric Lease Morgan, Librarian and Digital Humanist

I really want to argue that the question is not physical manifestation OR inherent message: the two cannot be separated so easily. It is true that digitization as it is currently primarily practiced offers the most in terms of textual access. And there’s been some very interesting work done in computational linguistics with works from the early modern and later periods. I might have something more to say about that in another post. But as I hope is indicative from this post, what a text means cannot be separated from the format in which it appears.

Hmm. I’m not quite sure I agree with “what a text means cannot be separated from the format in which it appears”. I could certainly agree with “what a text means cannot always be separated from the format in which it appears”! I could also agree with “for scholars of the text, what a text means cannot be separated from the format in which it appears”. I really believe that for the vast majority of use cases, the meaning of a text can be separated from its format and substrate.

Excellent post, Sarah! I’m not going to say much about what physical books offer beyond their digital counterparts (that’s what most of my blog is about, after all) but I do have a couple of comments about issues/problems you raise here — namely, what might be called the problem of the “census,” of finding out how multiple copies of the same edition compare. As you say, that takes time and money, and up to this point there are precious few books that have gotten the full treatment. The Shakespeare First Folio is probably the best known — and, incidentally, probably one of the reasons that “fetish” can be used in a derogatory sense, since non-Shakespeareans or non-early-modernists have, in my experience, generally been shocked at all the attention we’ve bestowed on that book in the last century. There is Owen Gingerich’s census of Copernicus (which was mighty difficult to accomplish); and a couple of incunabula (Gutenberg bible, Nuremberg chronicle); the Audobon Birds of America; and most likely a few more, if I did some actual digging around. Allison Wiggins’s (fantastic) article was a product of a partial census of Renaissance Chaucer’s, and she really stresses the value a full census could provide, by listing some of the conclusions she came to from her project — many of which provide hitherto unknown confirmation for some of the basic assumptions scholars hold about Chaucer.

A full, page-by-page census is nearly impossible unless the book already holds enough cultural capital to convince someone to pony up the financial capital — but, at the very least, what digital tools can and should offer us is a way to find out how many copies are extant, and where they are, with some reasonable measure of accuracy. These tools have hitherto not been designed to accomplish this at all, and I suppose I continue to hold out hope that the ESTC will, someday, do something along these lines (the addition of copy-specific information in their records from major libraries has been great, and I’ve certainly made a few finds that way in the last couple of months). This would still take time and money — but the rewards can be so high. (I remember, years ago, sitting in the rare book room at the U. of Illinois, at the time undertaking a major, grant-funded cataloging project, and watching a major Spenser scholar gape incredulously as the staff brought out a copy of the Faerie Queene that nobody (even they!) knew existed). Public institutions, especially, could benefit from knowing the value of the books they already own, and at an expense that, really, for the most basic information (look, we have one here!), isn’t out of reach.

That’s an access issue, both globally (so scholars anywhere can see the distribution) and locally (hey, I didn’t know we had these things right here!).

And, sorry, one last comment on the “fetish” — I normally see it used as a kind of shorthand, characterizing book-sniffers as out-of-touch. It can, at times, be a product of questionable (even lazy?) writing or thinking, but it does put the onus on book historians to explain what this all mean, why it’s important, why folks should pay attention. Ok, I’m really done now.

Adam, I’m so glad you made this point! If we stop thinking about digital tools as being about reproducing the text we could move on to the sorts of more radical democratization of access to physical texts that you suggest here. I am, as I fully acknowledge, extraordinarily privileged to work at the Folger, where there is a wealth of materials for me to look at. It’s mind-boggling. But I totally believe–and your blog completely supports this–that there is plenty of rich material at other, less obviously spectacular libraries. If we could have a census of copies that we could access, even if not full digital copies and even not as richly cataloged as the Folger’s copies are, that census could go far in helping us learn more about how copies aren’t editions and about the serendipity of research. It’s significantly less expensive than full-on digitization and potentially much more useful. I do have hopes that ESTC will make something like this happen. They did get a big grant to work on this, and they’ve been playing around with gathering a commons of digitized eighteenth-century works. I’d love to see this come to pass! Let’s make this a rising tide for all libraries, and not yet more evidence of how the rich get richer, while everyone else limps along with less and less. It’s good for all of us to know where all the riches are, and that really is something that digital projects could help make happen.

Brilliant post. As an early modernist who is also invested in building the digital humanities, this subject is near and dear to my heart. Digitization has made my dissertation possible. Although I spent 3 months in the Archives, research funding for graduate students has rapidly eroded and I finished a good portion of my research using digitized sources.

To answer the question, regarding what you lose with current digitization process that goes beyond fetishization – the ability to see the paper and material. I work with ballads and only in life or high quality color reproductions can I tell certain things about the creation of the ballad, not just what was in it. Further, things like glue marks, nail holes, or other such attributes on the back of the ballad are essential to helping me determine how early modern men and women may have used, read, or displayed ballads. Additionally, some of the papers have smoke damage, finger smudges, and the like, all of which are “invisible” in current black and white digitizations. For those of us who work in material culture, seeing the actual item (in person, but 3-d rendering or full color is good too), is essential to our work.

The English Broadside Ballad project at UCSB http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ is tackling this issue head on. Although they started wit black and white reproductions, they are slowly adding in high quality color images of each ballad. Where possible, they have a full color, black and white, ballad facsimile (ballad text re-typed in Roman font for easier reading, but re-insterted on the ballad page), text transcription (just the text, again in Roman font), and a sound recording of the sung ballad where possible. It’s an incredible endeavour and they are doing a top-notch job. Here’s an example: http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/31775/citation

I hadn’t thought about the issue of the backs of broadsides, but this makes perfect sense to me and is a wonderful example! And thanks for sharing the link to the English Broadside Ballad Project. I hadn’t actually looked at it in a long time, and there’s some exciting stuff going on there I wasn’t aware of.

I’m wondering if you’ve heard of the Internet Archive’s digitization efforts? Up until recently I was a book scanner working on the project. Over five years I scanned something like tens thousand books, including multiple copies of the same book (sometimes from the same edition), but we offer the scanned books free to the public in a variety of formats, including the raw, high-resolution image files that would retain all or most of the detail you’ve mentioned. (Blank tissue pages were not included, and there were sometimes reasons other pages were not included, but those are fairly rare circumstances, in my experience.)

Additionally, our scanning project is non-destructive. (I say “our” and “we”, but I no longer actually work there.)

I do know the Internet Archive’s work and I agree: they are doing some great stuff. Not only do they scan the entire object, cover to cover, but as you point out, you can sometimes find multiple copies of the same edition. And the variety of formats the works are available in are great! I wrote a post about the recent attention Brewster Kahle has gotten for saving the physical copies of books along with the scanned copies. Really, the whole project is fascinating!