>

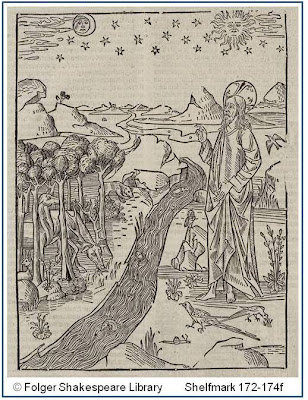

It’s been a while since I turned to the 1527 Bible, but we’re not done exploring yet. We still have to look at one of its most striking features: the full-page woodcut. Go back and look at previous blogs on the book if you want to see it in context of the page opening. It’s opposite the beginning of Genesis–a fitting choice for a depiction of God creating the world. Above is the woodcut itself, ready to be admired. It’s a beautiful picture.

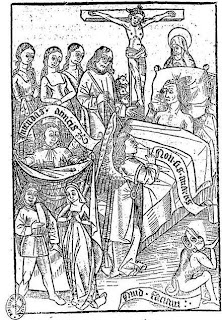

According to the Bibliographie Lyonnaise (a monumental bibliography and key reference source on early modern books printed in Lyon), the woodcut was made by an artist it refers to only as “the master of the Ars moriendi of Jean Siber.” If you look further in the Bibliographie Lyonnaise and then follow that with research on the Incunabula Short Title Catalogue, you’ll discover that Jean Siber was a Lyonnaise printer associated with an edition of an Ars moriendi that was printed in the early 1490s (there’s some disagreement about whether he was the printer or someone else). If you then go to Gallica, the online digital collection of the Bibliotheque nationale de France, you can find not only a record of this Ars moriendi (which they attribute to the other printer), but you’ll also be able to access a pdf of the book! There are twelve illustrations in the book made from nine different woodcuts. First, here is one of those woodcuts:

Is there a connection to our woodcut of the creation of the world? To my (admittedly untrained) eye, there are similarities in style.

Is there a connection to our woodcut of the creation of the world? To my (admittedly untrained) eye, there are similarities in style.

And now, I’ll return to that number–in the Ars moriendi one woodcut was used in three different locations, so that there are twelve illustrations made from nine woodcuts. That practice is not unusual for the period. Far from it–woodcuts were often used more than once in a single book and they reappeared in other text as well. It’s helpful to remember that woodcuts were hand crafted, that they were an investment of time, labor, and money. Why use it once when you can use it multiple times and spread out the cost? That beautiful illustration of the creation of the world we’ve been looking at? Jacques Mareschal used it repeatedly in Bibles he printed between 1523 and 1541.

Oh, and what’s an Ars moriendi? It’s a work that teaches you how to die well: the art of dying. Perhaps there will be more occasions to think about the connections between dying and printing.