I. Reproducing

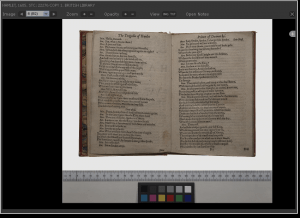

First: digital facsimiles, both of the quality that we’ve seen in EEBO but also in higher-resolution images down by various libraries and institutions (the Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image (SCETI), Furness Collection, Penn):

More infrequently: digital editions, including the relatively straightforward text-and-nothing-but-the-text (the Gutenberg, which you can read online or download in a nice variety of formats) and the slightly more complicated text-and-annotations (Thomas Luxon’s The Milton Reading Room):

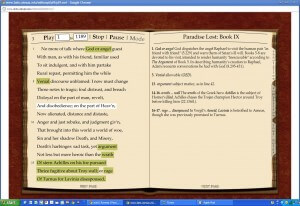

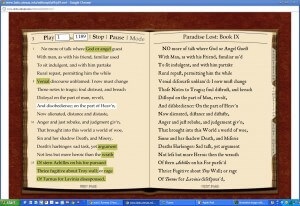

And the more ambitious, such as this combination of audio and text (from UT-Austin’s Liberal Arts Instructional Technology Service (LAITS)):

I suppose we ought to also include audio, such as from PennSound and LibriVox.

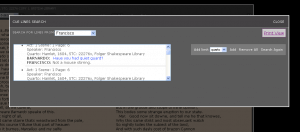

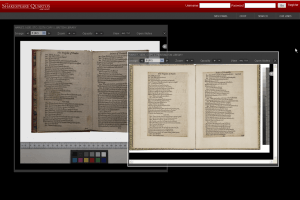

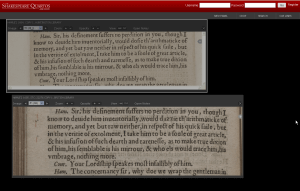

There’s also archives that strive to move beyond reproducing to enabling different uses of texts. The Shakespeare Quartos Archive is one possibility:

The edition experience changes with newer platforms. There’s the standard Kindle app (as seen on an iPad):

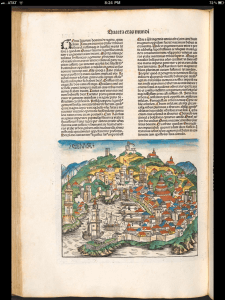

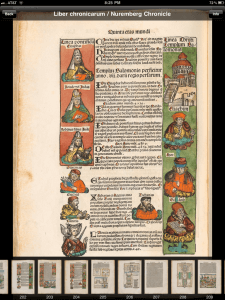

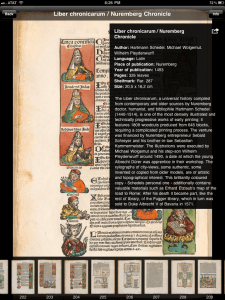

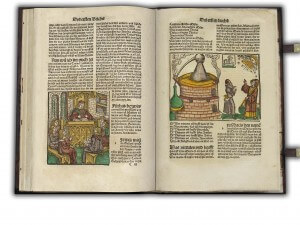

More interesting: high quality, full-color facsimile (here shown by the Bavarian State Library’s app, displaying their Nuremberg Chronicle, which happens to be Schedel’s own copy):

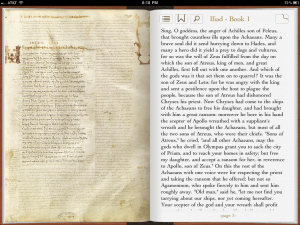

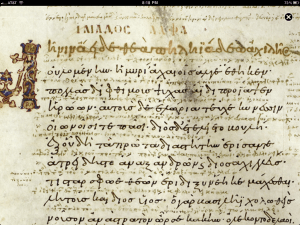

Even more exciting, a facsimile combined with transcription (here shown in the University of Kentucky’s Vis Center’s app of the Iliad and the Venetus A manuscript):

A warning: the desire for beautiful facsimiles can sometimes lead to Frankentexts, in which images of pages are joined together to make a reproduction of a book that never existed nor would never exist (here the National Library of Medicine’s Turning the Pages app showing an opening in which the recto of a page appears on the left-hand side of the opening):

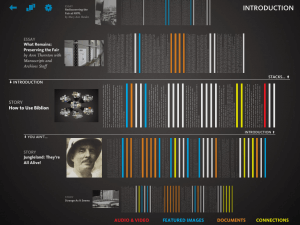

But there are also apps that move out of codex reproductions to incorporate different media–text, photographs, video, sound–in non-linear arrangements (here, Biblion, a magazine from the New York Public Library):

There’s no edition of Paradise Lost that is nearly as ambitious as these, but the ability of apps to move between facsimile and edited text, between annotation and imagery and sound, and to move both linearly and circuitously could open up interesting possibilities for how we could produce and use Paradise Lost.

2. Analyzing

It’s worth starting off by pointing out that computing technology has long been harnessed to authorship studies: Donald Foster’s use of computers to analyze linguistic features of various early modern (and modern) authors and then to extrapolate from those characteristics the authors of unattributed (or misattributed) works is one example of this. (Although not a very good or interesting example.)

More interesting are more recent development of computational analysis of linguistic features that would be otherwise hard to discern through reading–“distant reading” is Franco Moretti’s phrase for it.

There’s been some recent splashiness about this. Google’s n-gram feature and the Culturomics team from Harvard last fall got a lot of attention for studying concepts like fame through the use of the word and approaching the concept through the frequency of, for instance, famous people’s names in print over set periods of time.

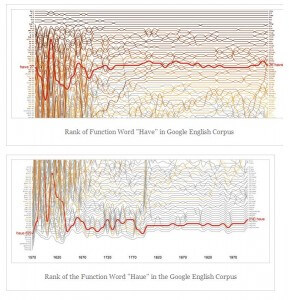

Mike Gleicher has a great visualization of popular words that he gathered from analyzing the Google Books corpus, which tells us something about language but also, Mike Witmore suggests, maybe something about what’s missing from Google Books (and I think it’s possible it tells us something about the history of print and fonts):

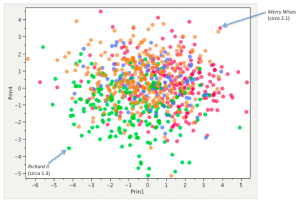

More relevant to our period is the type of work done by Mike Witmore, Jonathan Hope, and Martin Mueller. Witmore and Hope, in a recent Shakespeare Quarterly article, argue that it’s possible to discover genre markers at the sentence level. Comedy isn’t just characterized by marriage at the end of the play, but by first-person pronouns. (Below is a map of linguistic features of the entire body of plays; for more info read their SQ piece.) Figure 1: 776 Pieces of Shakespeare’s Plays from the First Folio, each of 1000 words, rated on two scaled principal components (1 and 4). The color key for the dots: Histories (green), Comedies (red), Tragedies (orange) and Late Plays (blue). Late plays are: The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline, Henry VIII.

Are there textual markers in Milton’s prose that reappear in Paradise Lost? Can we trace influences through a large-scale linguistic analysis?

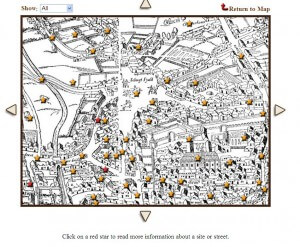

There’s also non-linguistic analysis, such as Janelle Jenstad’s Map of Early Modern London (U Victoria):

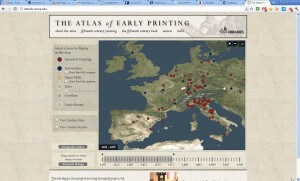

The Atlas of Early Printing (U Iowa Libraries) does something similar for incunabula:

Might we be able to discern patterns in the book trade through these sorts of interactive maps?

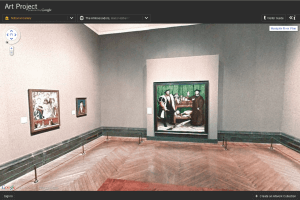

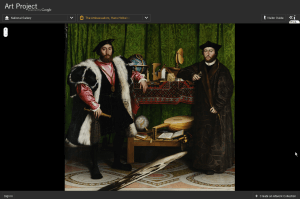

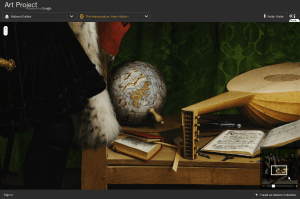

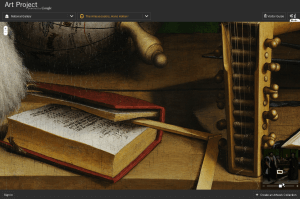

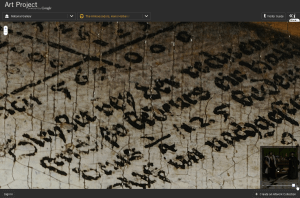

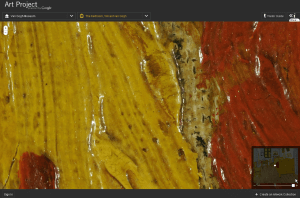

Google Art Project is not about books, but might it offer an example of what digital tools can do that the naked eye cannot? Here, what seems to be about reproduction turns into analysis of production:

3. Teaching

Obviously, these are all resources that can be used in teaching. But there are also folks who are using the production of digital humanities projects as classwork: instead of (or in addition to) writing research papers, students build digital resources. Janelle Jenstad’s students contribute to the map. Jeff McClurken, at Mary Washington, has his students build digital exhibits:

How might we be able to teach Paradise Lost or Milton through the creation of digital projects?