I just got back from a wonderful trip to Rare Book School to deliver a talk in their 2015 lecture series. It was the last week of their summer season in Charlottesville, the week when the Descriptive Bibliography course (aka “boot camp”) was in full swing, and the weather was in all its hot, glorious humidity. I wanted to keep things light as well as make some points I feel very strongly about: the importance of librarians and researchers using social media to help sustain special collections libraries.

Below are the slides and my notes for my July 29th talk. Since RBS records and shares the audio of their talks (go browse through past RBS lectures and listen!) I have, with their permission, also embedded the audio of my talk here so that you can listen and read along if you’d like (there are some variations between the two, though nothing substantive—I’ll leave you to decide which is the authoritative version…). I have in most cases linked my slides to the digital assets they’re showing. I’d like to express my thanks to the staff and students of Rare Book School for being so welcoming and for participating in an invigorating discussion.

How to Destroy Special Collections with Social Media in 3 Easy Steps: A Guide for Researchers and Librarians

I’ll start with a quick definition of social media: it’s a platform for sharing images/text/sound with others, something like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, blogs, Tumblr, Snapchat. It often has a reputation as being a place that is purely trivial—where people talk about what they had for breakfast. It can be that, but it can also be a place to foment social and political revolutions and to find like-minded friends on the other side of the globe. But I’m here today to talk to you about how to use social media to kill special collections.

The first thing to know is that plenty of special collections are already a presence on social media; the Special Collections + Social Media wiki lists approximately 185 institutions on twitter, 115 tumblrs, and 170 blogs in this field—numbers that don’t include individual librarians, researchers, collectors, and dealers on those platforms.

Whether you like it or not, social media is out there and we need to think about its impact. So with that preface out of the way, let’s look at how you, too, can destroy special collections with social media!

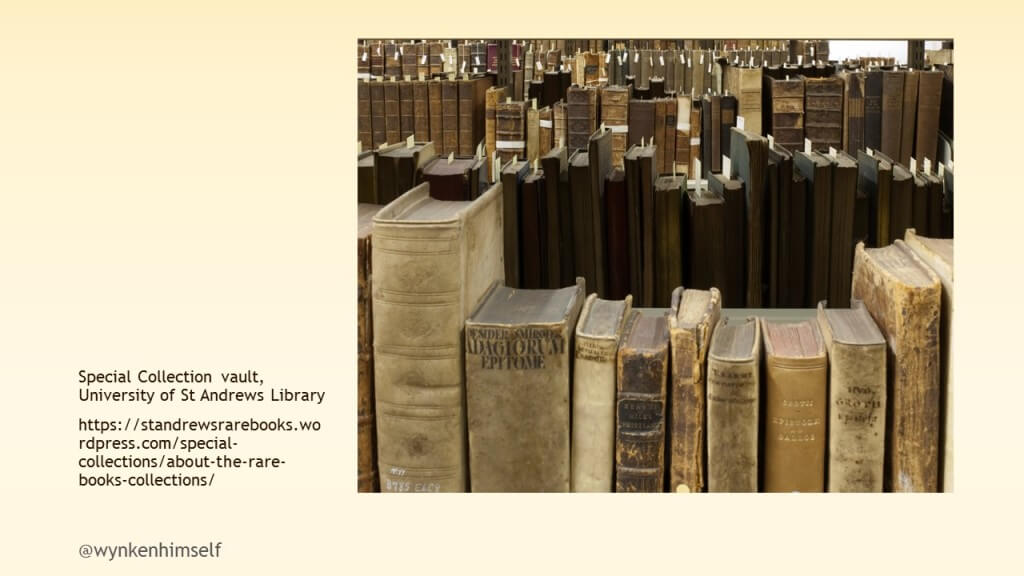

The single most important way to kill special collections with social media? Do not have any images that anyone can share. Keep them locked up tight.

How do you achieve that goal? First: don’t digitize anything!

Let me tell you a story: Last summer I was lucky enough to be visiting London and to get a tour of Lambeth Palace Library. It’s an amazing place! We had a great tour, met some wonderful librarians, had a lovely time. While I was hanging out in the reading room, waiting for my friend Adam to do some actual research, I was paging through this gorgeous book on their collection treasures.

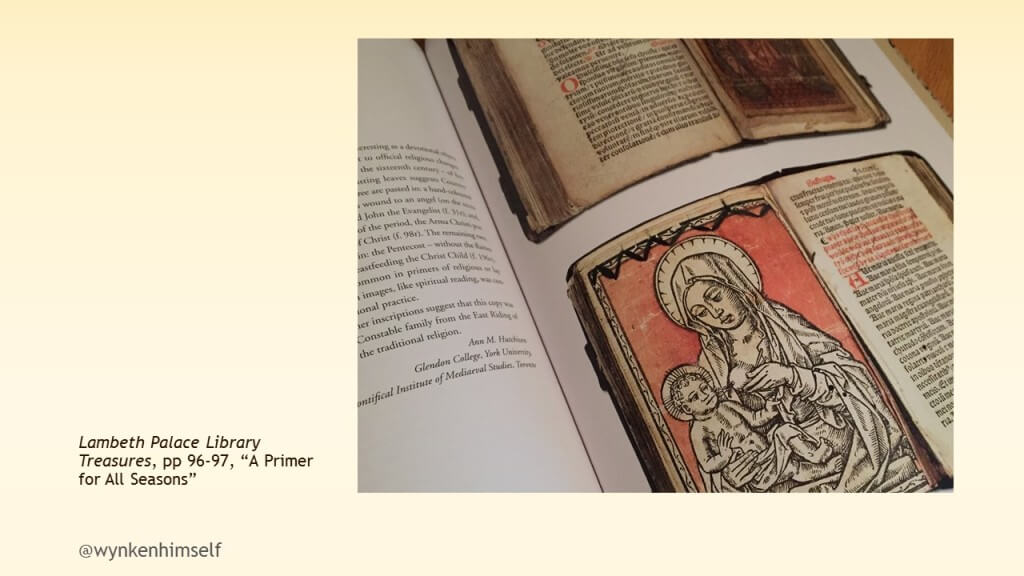

And I came across this astonishing image—it’s a 1537 primer extra-illustrated with images sewn in, and marked up with deletions. I love the little I know about this book, what it shows us about how people used their books.

Fast forward to this summer, when I’ve been trawling through digital collections looking for things I want to include in the website accompanying my handbook. I remembered this Lambeth Palace primer and wanted to include some images of it. I know the images exist because look: there are two right there in the treasures book. I just need to find them.

First step: the Lambeth Palace Library website. Now’s not the time to take you through the principles of web design and optimizing content, although I have a lot to say on that subject. I’ll simply say here that I couldn’t find anything like a digital collection under “services” or “about collections” or anywhere else …

… although I did find a link to Bridgeman Art Collection, a for-profit management system for licensing images. Lambeth is there, and the image of the nursing Mary was there, too, but I wasn’t interested in buying a commercial license for my non-commercial site. So I went back to Lambeth’s site and decided, out of an insatiable curiosity, to look at their digital exhibits.

And there, in an exhibit called “With a little help from our friends,” was my book with a link to “click for full sized image” and …

… voilà! There’s the opening from that awesome book! It’s so great. Look at that stitching! Alas, Lambeth’s terms state there are fees for using the image for anything other than research or private study, so I’m afraid I won’t be including it in my site after all. But that brings me to an important aspect of locking up your images:

If you are interested in killing special collections, and you do make the mistake of digitizing your collections, make sure you make it impossible for anyone to share those pictures.

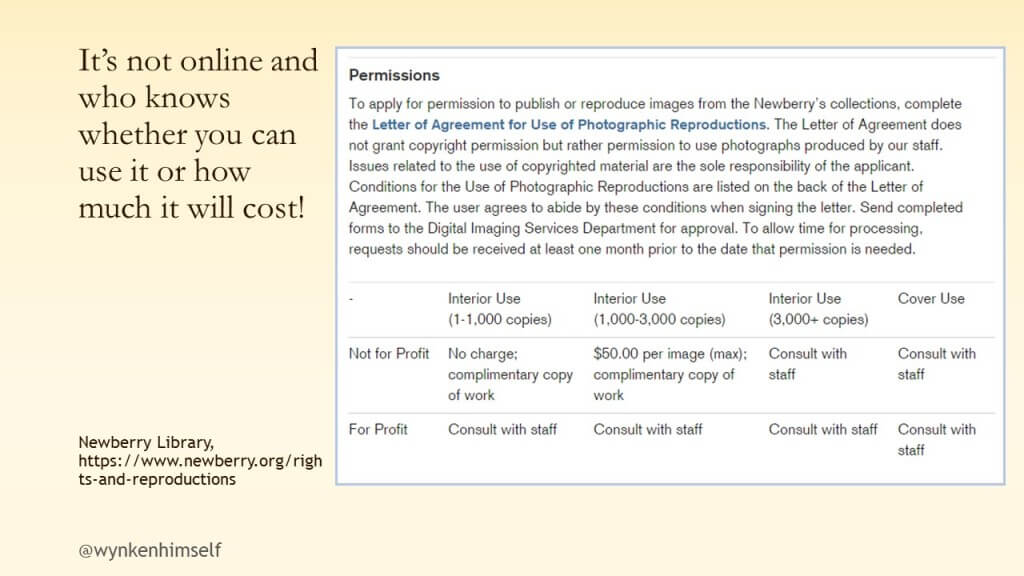

Luckily, there are so many ways to make it impossible for people to share your stuff! One straightforward option, the choice taken by Lambeth, and here illustrated by the Newberry, is to avoid putting images online and to charge for use. If I can’t find something in your library, I’ll go somewhere else to get my special collections fix, leaving yours to wither from disuse.

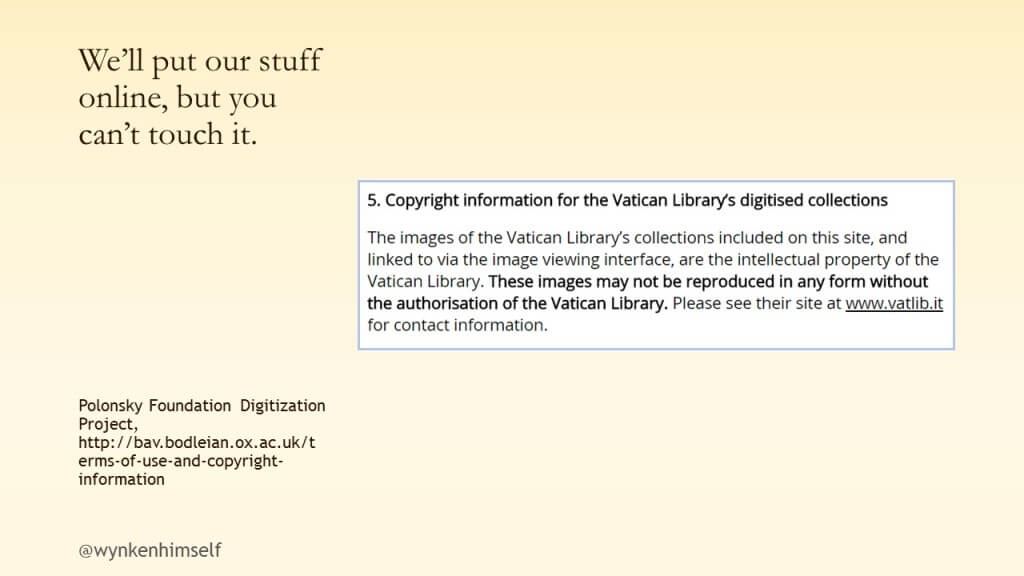

A more diabolical approach is to do what the Vatican does: put it all online and then assert all possible rights over it, telling people that they cannot reproduce them in any form whatsoever. (This is particularly upsetting since the Bodleian, in this collection, uses a Creative Commons Non-Commercial license.)

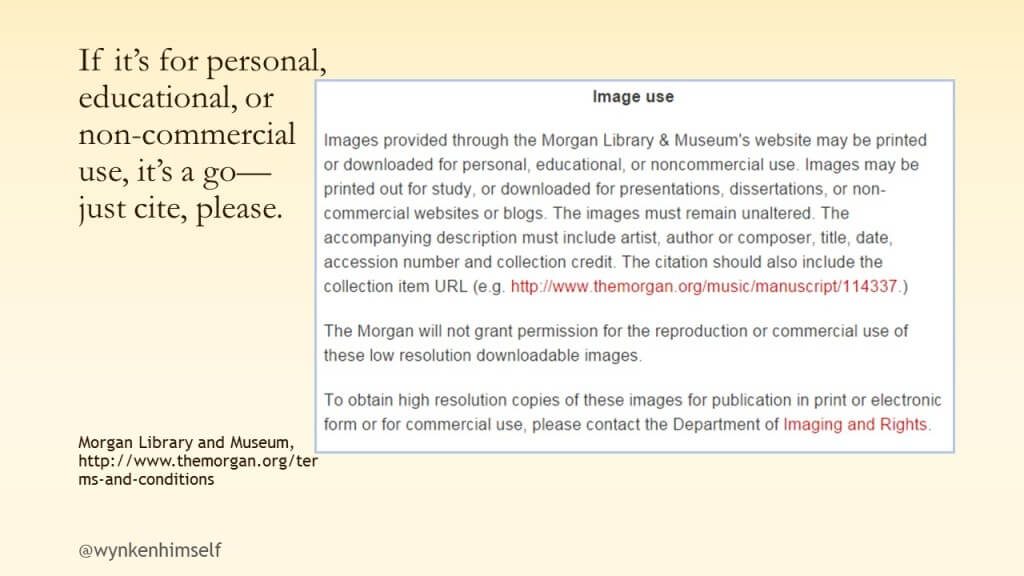

On the other hand, you could, like the Morgan, allow the use of images for personal, educational, or non-commercial use.

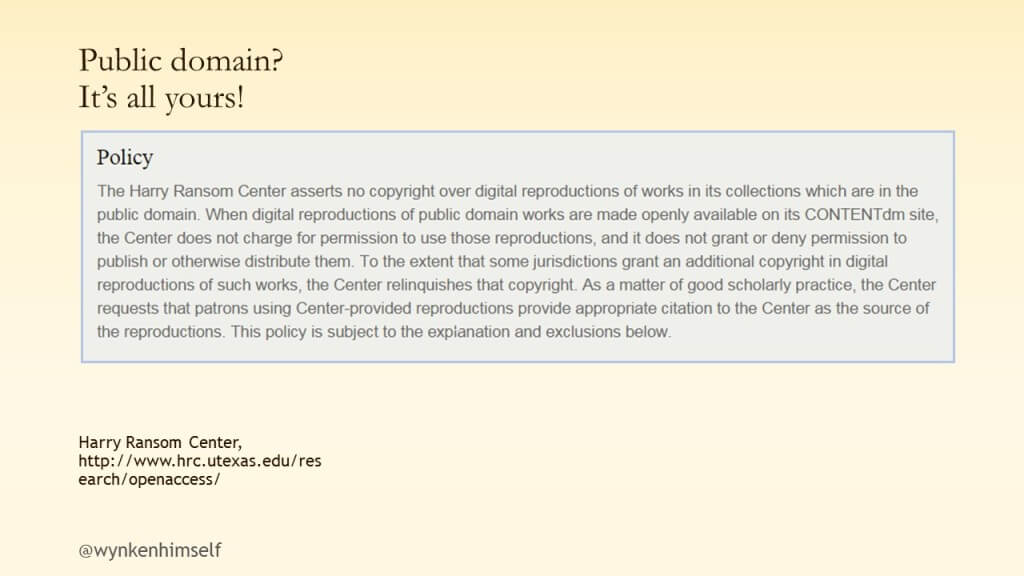

Or you could even recognize, as the Harry Ransom Center does, that exact photographic reproductions of two-dimensional works in the public domain are themselves in the public domain and users can do whatever they want with them! ((There was a lot of discussion about this in the Q&A, and there is a lot of confusion about this in general. The court case that sets precedence here is the 1999 Bridgeman Art Library v Corel. I am not a lawyer! But you can go talk to your own lawyers if need be. You can also read through the Wikipedia article on Corel and follow the links there for more information.)) Of course, if your aim is to stifle special collections, this approach is not the one you should take.

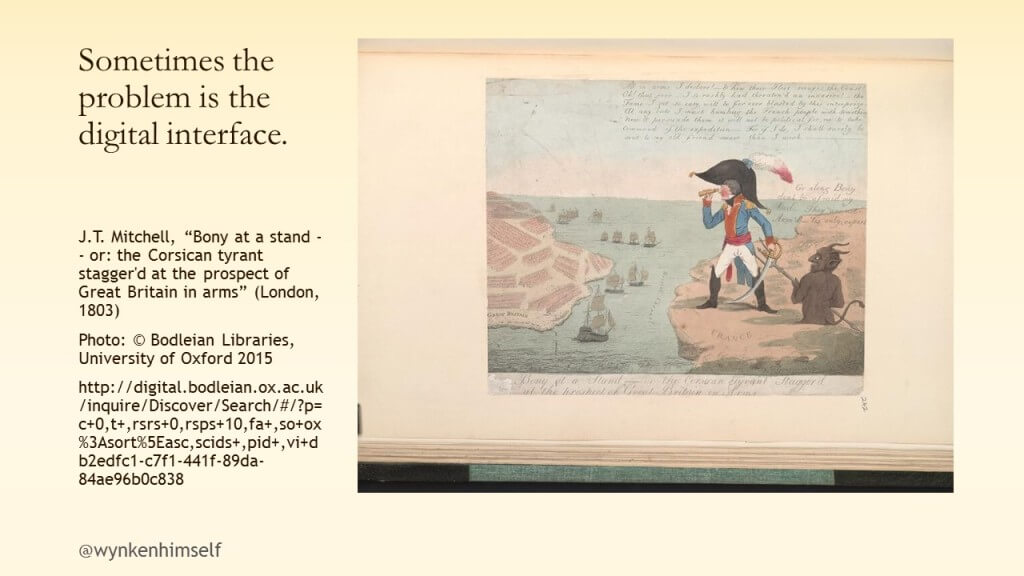

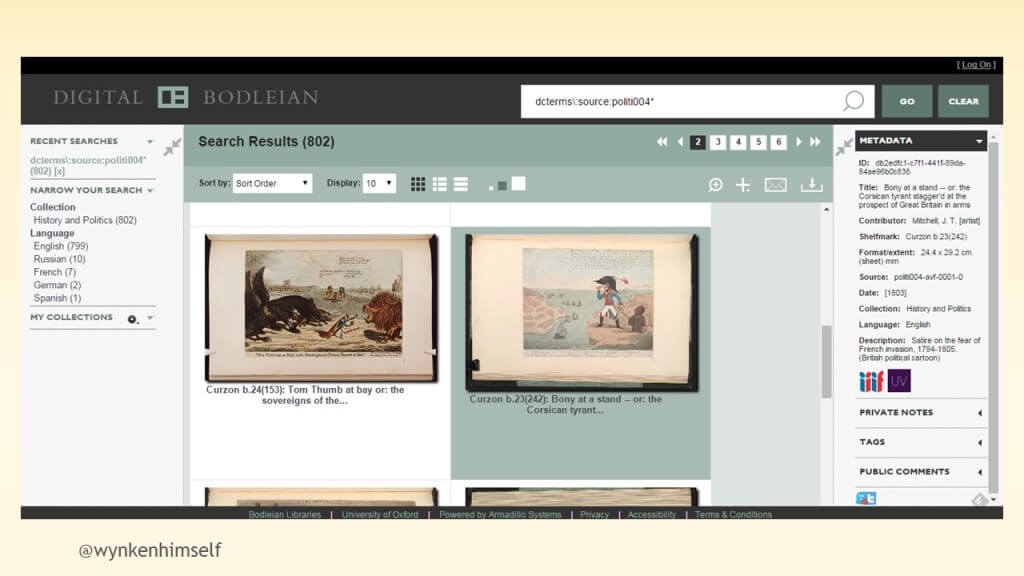

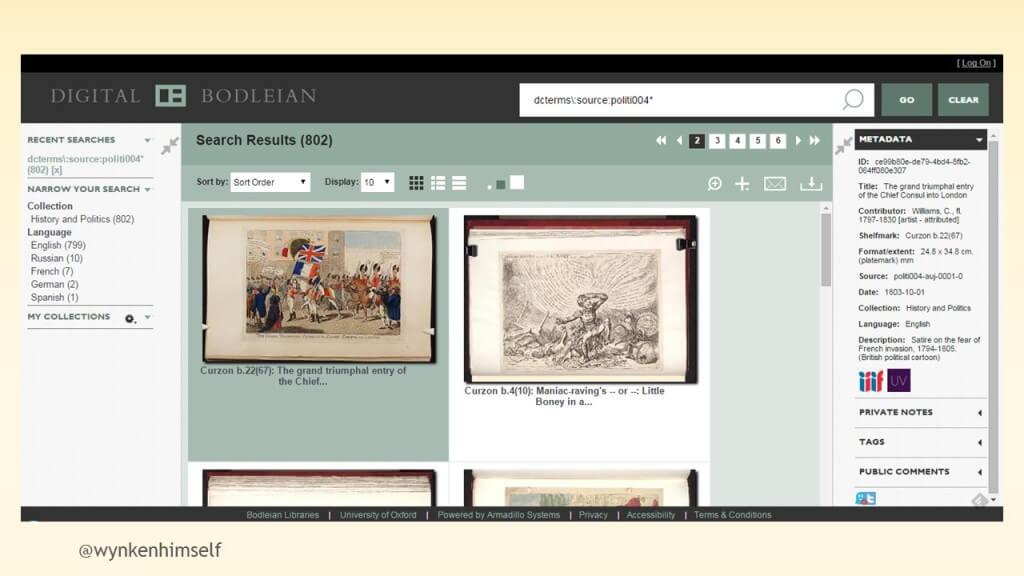

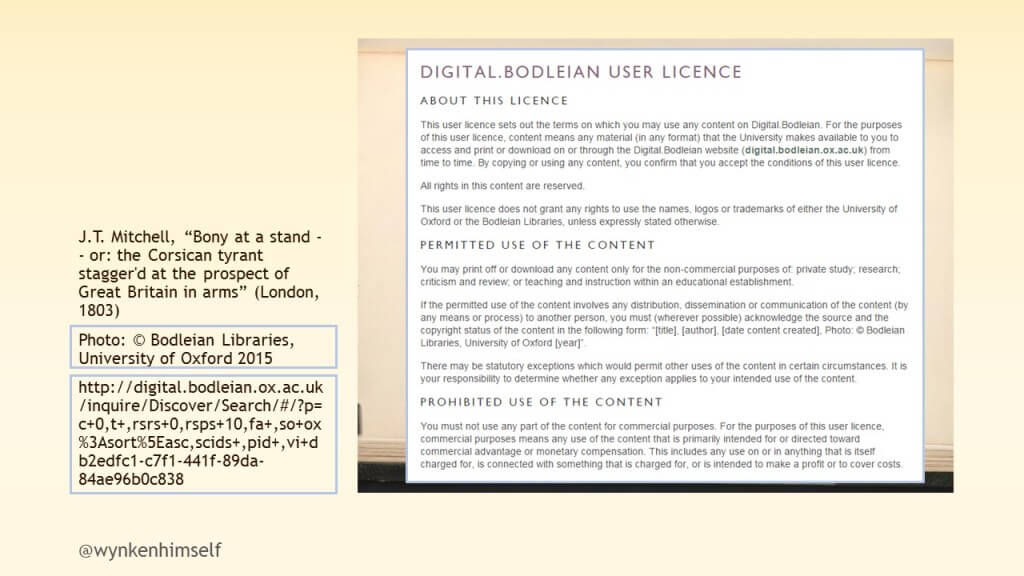

Licensing and copyright aren’t the only tools at your disposal to make things difficult. Sometimes just forcing people to use your website can be enough to discourage them. I found this image through the Bodleian’s new digital repository, Digital Bodleian. (It’s Napoleon being terrified of Great Britain, perhaps because he doesn’t understand their odd libel laws and websites.)

I came across it while I was browsing through their Curzon collection of political prints. Ah, I thought to myself, I wonder what’s going on here?

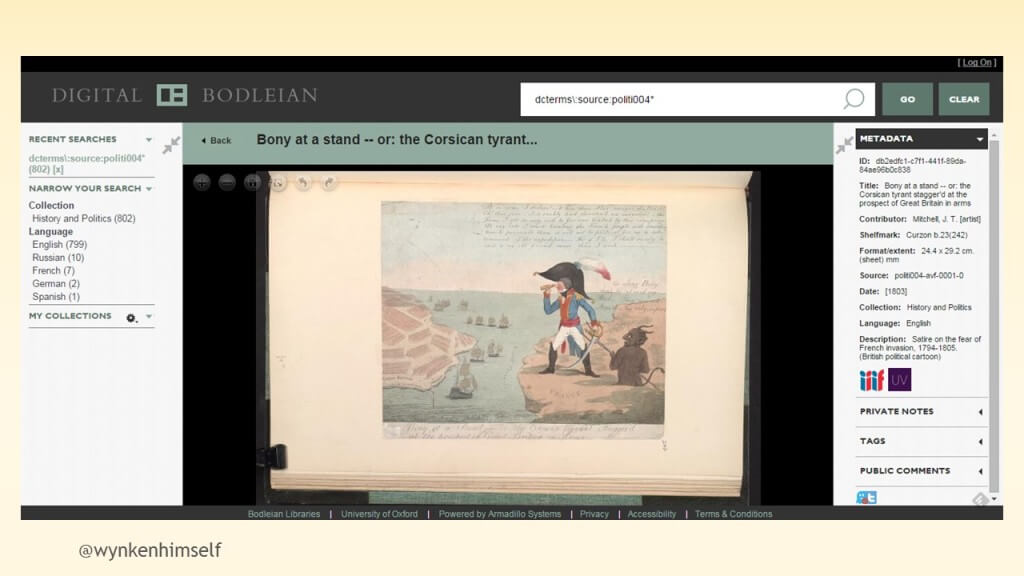

And so I opened up the image so I could zoom in and see greater details. Hmm, I thought, I’d like to download this image. I’ll just click on … on … And there doesn’t seem to be any option on this page for downloading the image. (Yes, I could right-click and save it, but I wanted a larger size and I wanted to download the associated metadata with it because I’m fussy like that. Alternatively, we could imagine that I have no idea about the right-click option, which is not uncommon among library users.) In any case, I’m pretty sure I saw a download option on the earlier view, so I’ll just click on that handy “back” link next to the image title and …

… I’m back at the previous page! Well, not quite. I’m at the top of the previous page, but after I patiently scroll through, I can find my image and download it so that I can share it with you.

So that was a bit tedious. Equally tedious is getting a url to share: that required cutting-and-pasting it from the address bar, resulting in the ugly—but stable—url you see here. Alas, because I’m a good citizen, I went to check the Digital Bodleian’s terms and I see that they claim copyright over this and all images on their site and that I’m only allowed to use it for the non-commercial purposes of private study, research, criticism and review, or teaching and instruction (but only within an educational establishment). So I’m good for this presentation, but on less happy grounds when it comes time for me to post this on my blog.

So that was a lot of work, even for something that was digitized and shareable! But what’s the payoff, you might be wondering, for letting pictures of your stuff be shareable online? Is it worthwhile making sure your special collections materials are circulating on social media?

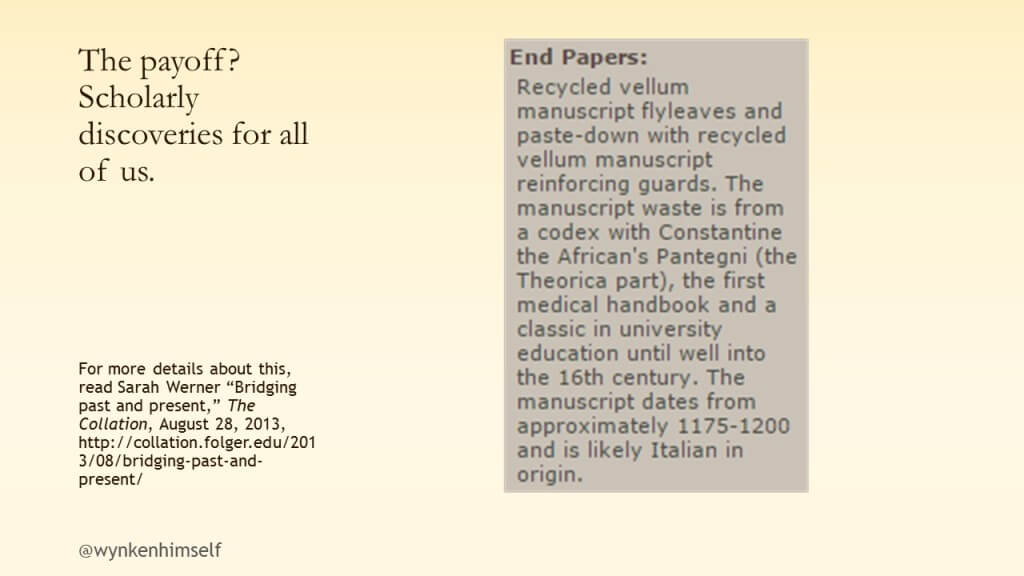

Here’s a quick story that might answer that question. The Folger, some of you might know, has a binding image collection, full of detailed pictures of all sorts of binding features from a wide collection of books. It’s pretty interesting.

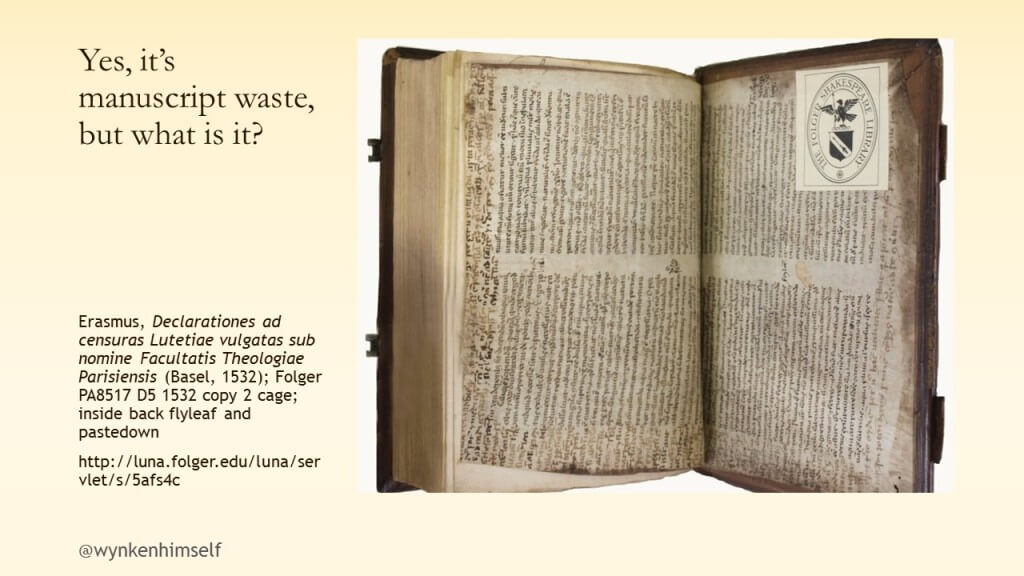

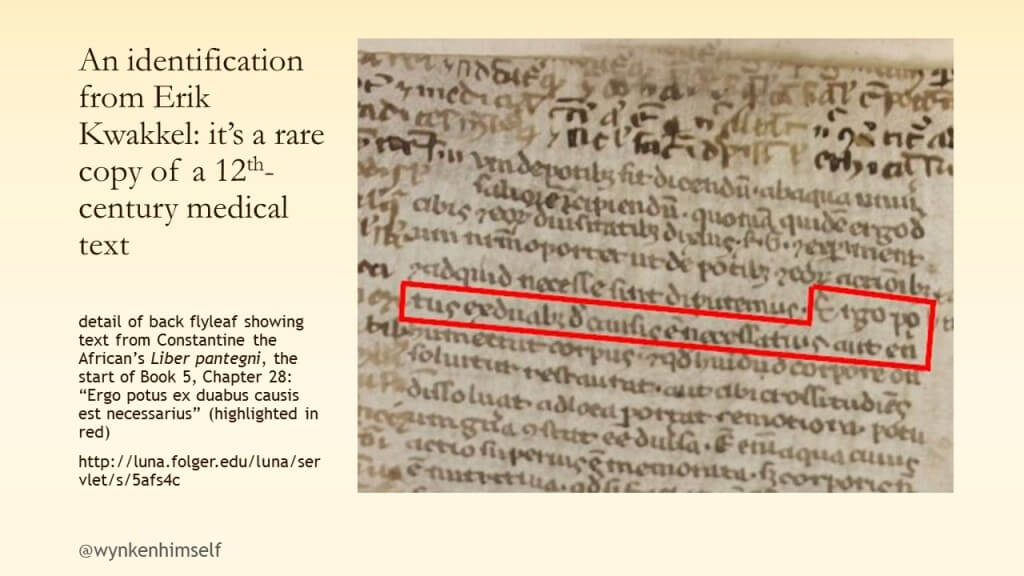

Some time back, the Folger hosted a conference about bindings and a number of participants were tweeting about the conference and this resource. Because of those tweets, Erik Kwakkel, a Dutch medievalist and book historian, was looking through the database and this book caught his eye. What, he wondered, was that manuscript being reused as flyleaves here?

After some close examination, he realized it was a 12th-century copy of a medical text, a copy that he believes is an unusually early one. Erik got in touch with the Folger and then, after some twitter and email correspondence, walked me through his identification.

The result of this open collection shared through social media? An updated record for the book and a blog post sharing his identification with all who use it. Not a bad payoff.

But our task is to bury special collections, not to praise social media. Step 2 for killing rare books and manuscripts with social media? Turn everything into dismissive LOLs and mere decoration.

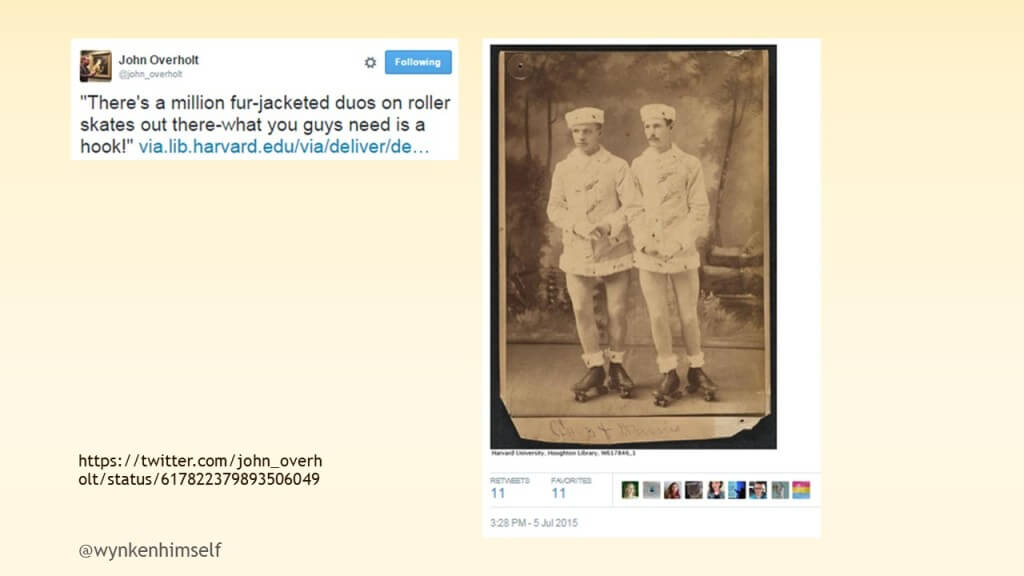

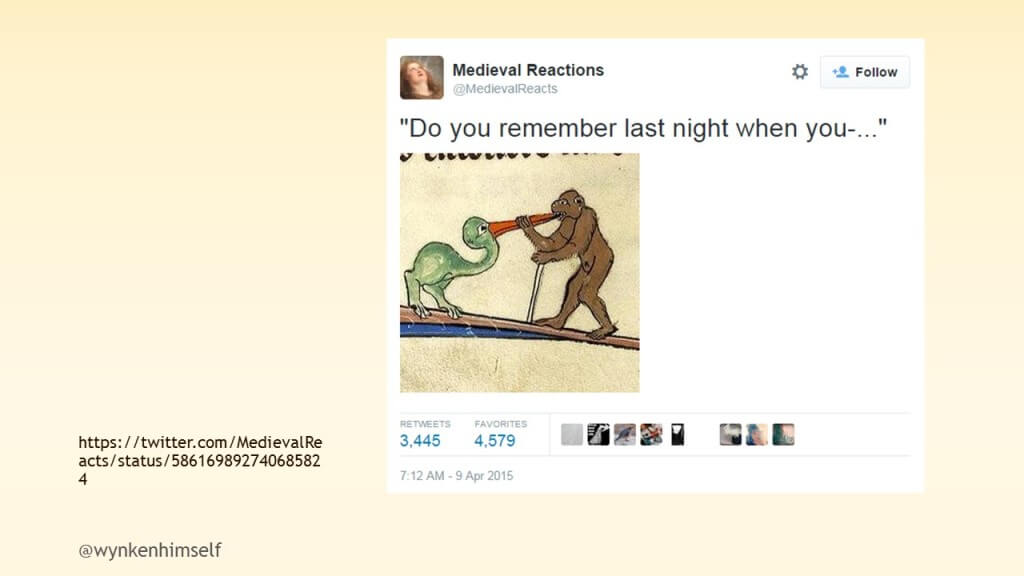

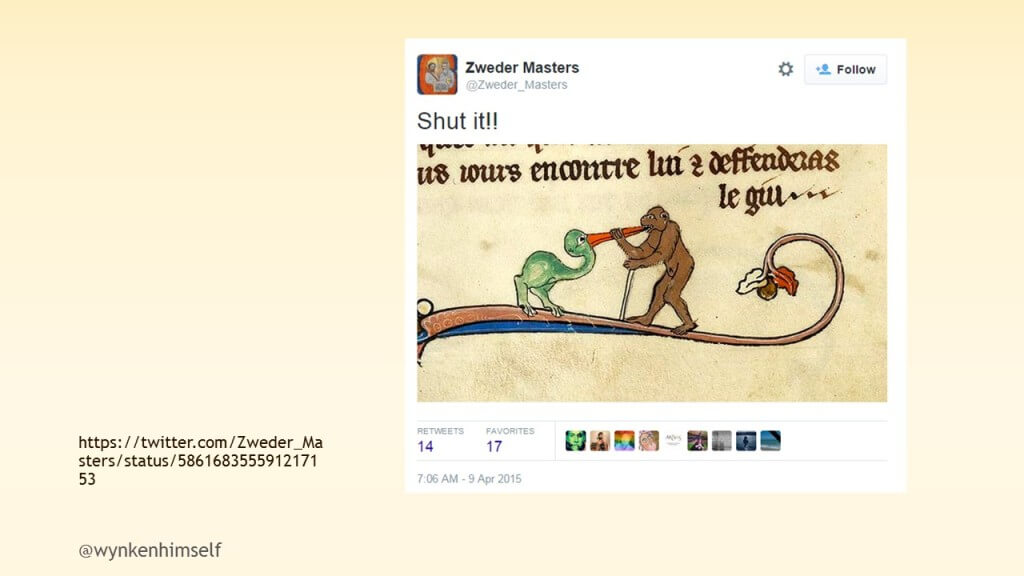

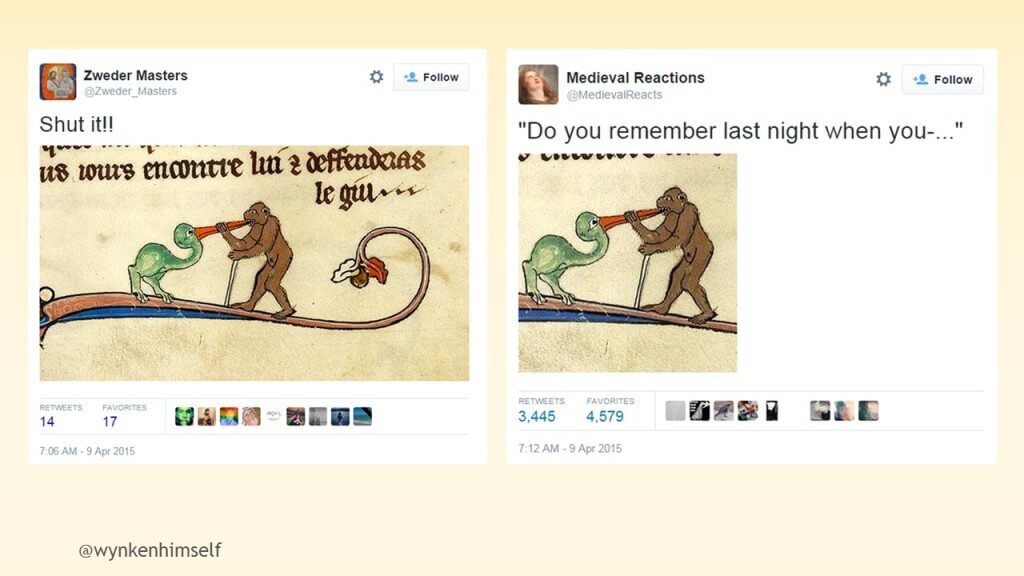

This spring there was something of a kerfuffle among medievalists on Twitter about a fairly new account called @MedievalReacts. The short of it was that this is an account created and run by a kid that gained incredible popularity through a network of accounts that help push out each other’s content. It has an insane number of followers and, like other professionally viral accounts, was designed to make its creators money.

What got the goats of a lot of medievalists, however, was their clear sense that MedievalReacts was simply ripping off their tweets—the images they had found were being taken, with no credit!, by this money-grubbing hack.

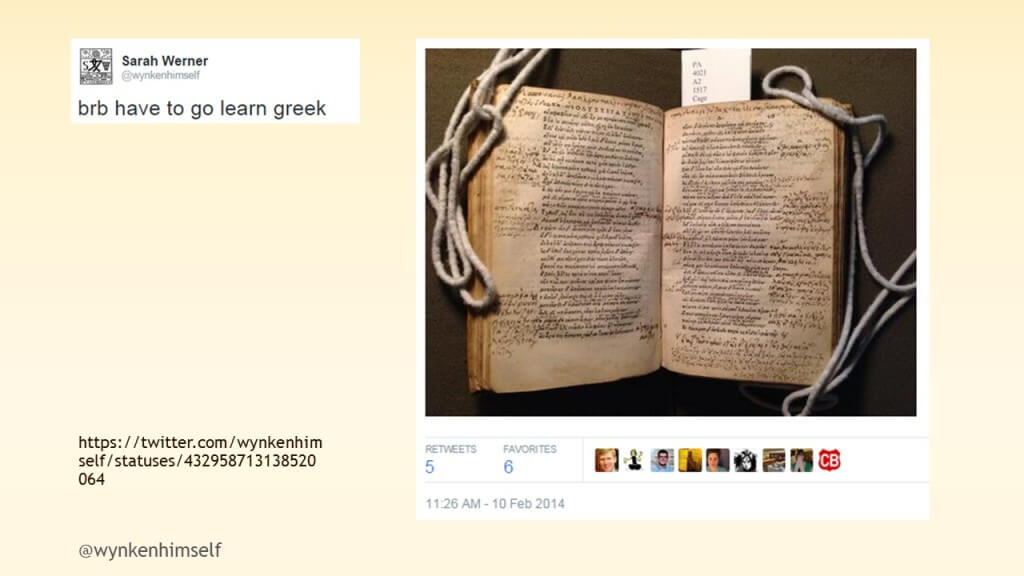

And clearly that is a large part of what MedievalReacts was doing. He wasn’t going around visiting libraries or digital collections and scouring images for funny pictures. He was scrapping images off other accounts and attaching new jokes to them. (The tweet on the left preceded MedievalReacts’ by only a handful of minutes.) Now I have no fondness for accounts like these. I wrote a long screed about HistoryPics and other accounts that take images and don’t credit the institutions and individuals who made them available. But how different is what MedievalReacts does from what so many academics do on twitter?

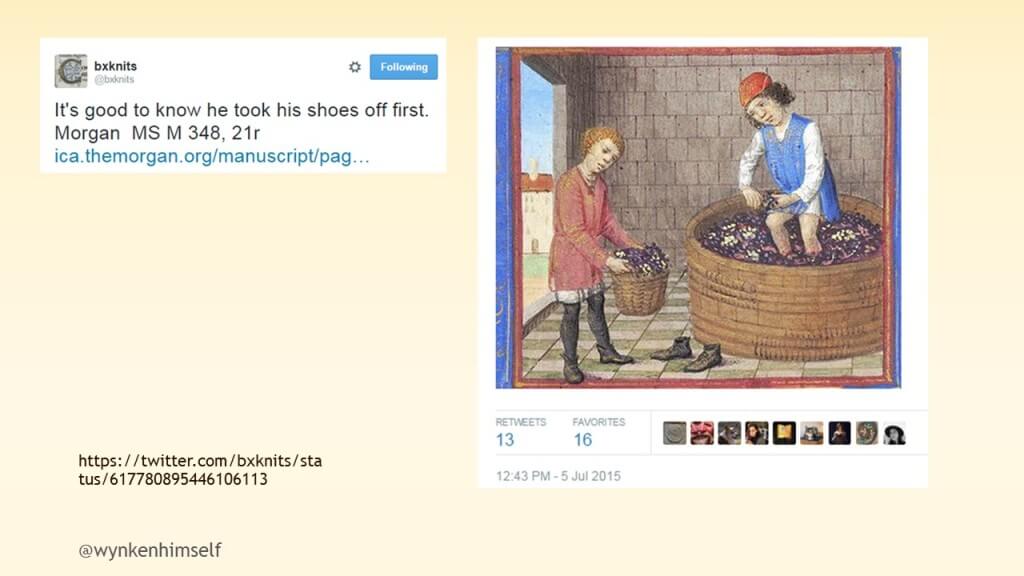

Another medieval manuscript with a funny caption …

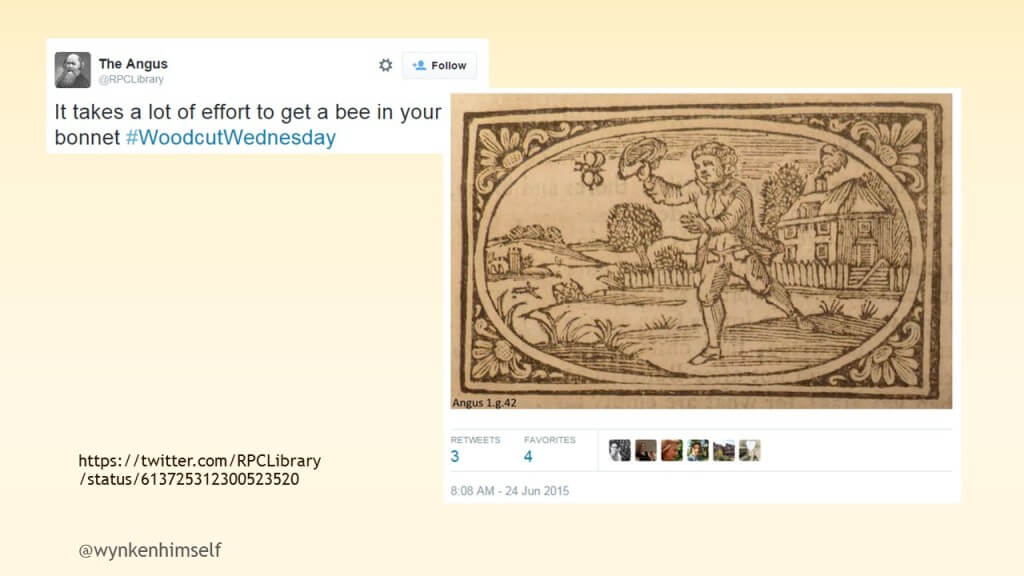

A woodcut with a funny caption …

A photograph with a funny caption …

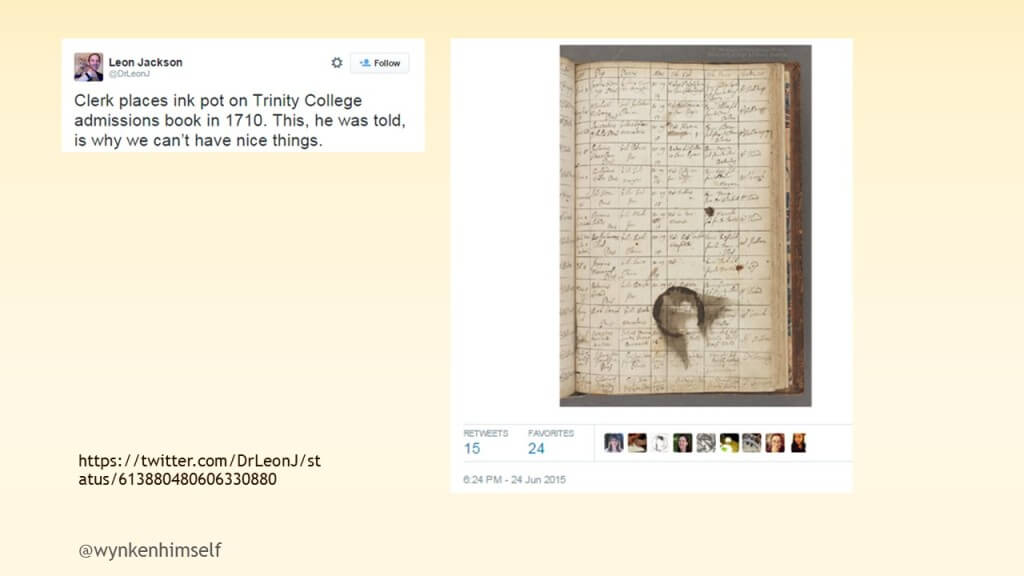

So silly jokes are funny and I like funny, as evidenced by my own contribution to this genre. But none of these tweets really add much to anyone’s knowledge of these works or create much interest in them beyond these individual pics. At least these four examples include citations for what’s being shown, either through links, text added to the image, or the inclusion of flags with call numbers.

But what about those that don’t include any sort of citation? I actually think this one is hilarious and smart about the kinds of connections people want to make between today’s internet culture (“that’s why we can’t have nice things”) and earlier information technologies (ink pots and ledgers). And the tweet resonated—I was one of the ones who retweeted it. But should it have included some sort of citation for the manuscript? Would a researcher quote a book and not cite it? Why are pictures any different?

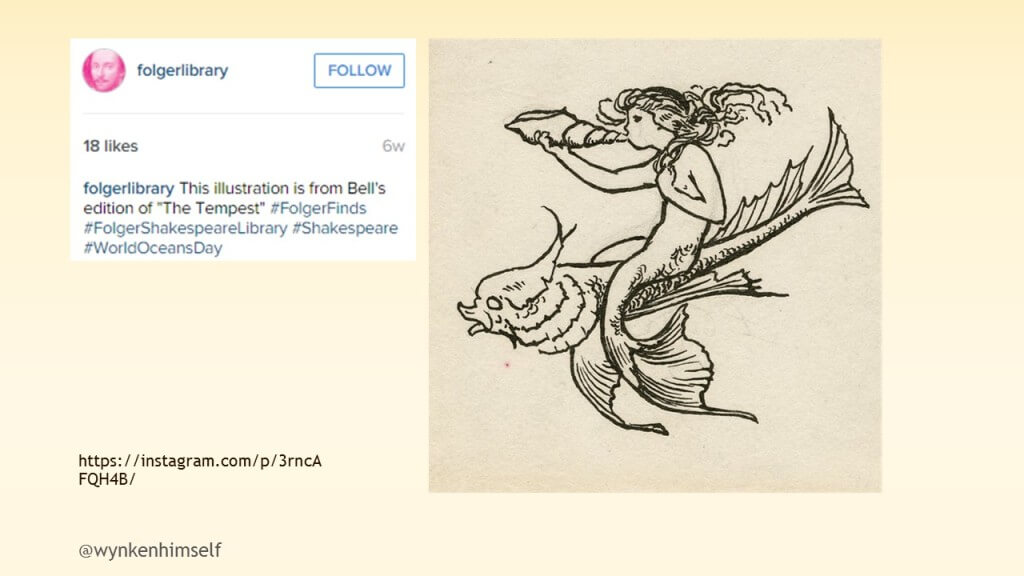

Here’s an Instagram that seems to provide a citation: “Bell’s edition” seems like it could lead you to an identification, if you don’t know that “Bell’s editions” of Shakespeare are so numerous as to be nearly uncountable and, in any case, this isn’t that Bell but Robert Bell. The pitfalls of the relationships between PR departments and special collections is a subject for another day, but this shows one potential problem of outsourcing social media to someone who isn’t a librarian or knowledgeable about the collection.

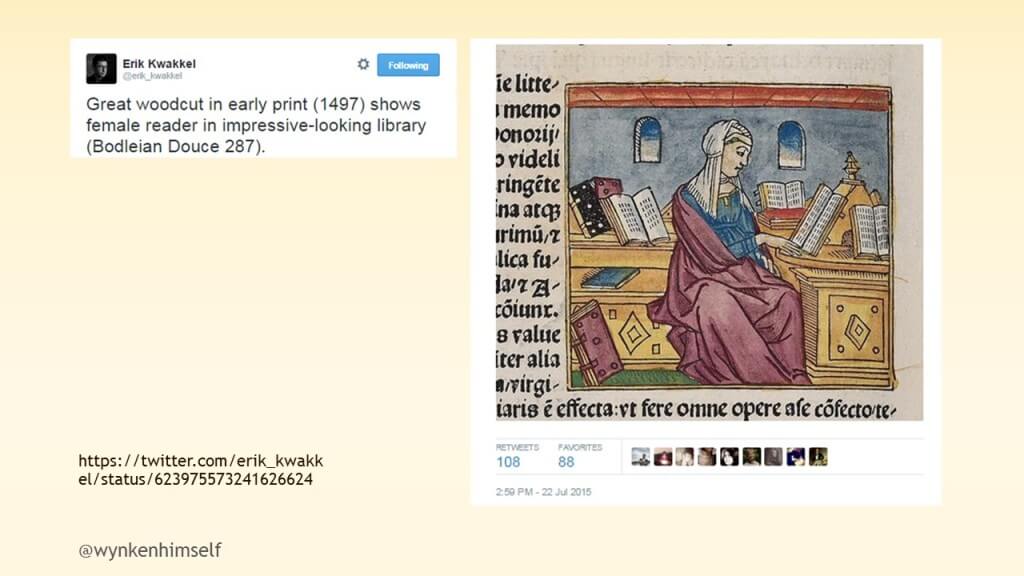

It’s not actually that hard to create tweets of visually interesting objects that help readers understand what it is and why it’s interesting and that lead them to a source where they can learn more about it. Here’s Erik, again, with a great picture and tweet that’s more than just a joke.

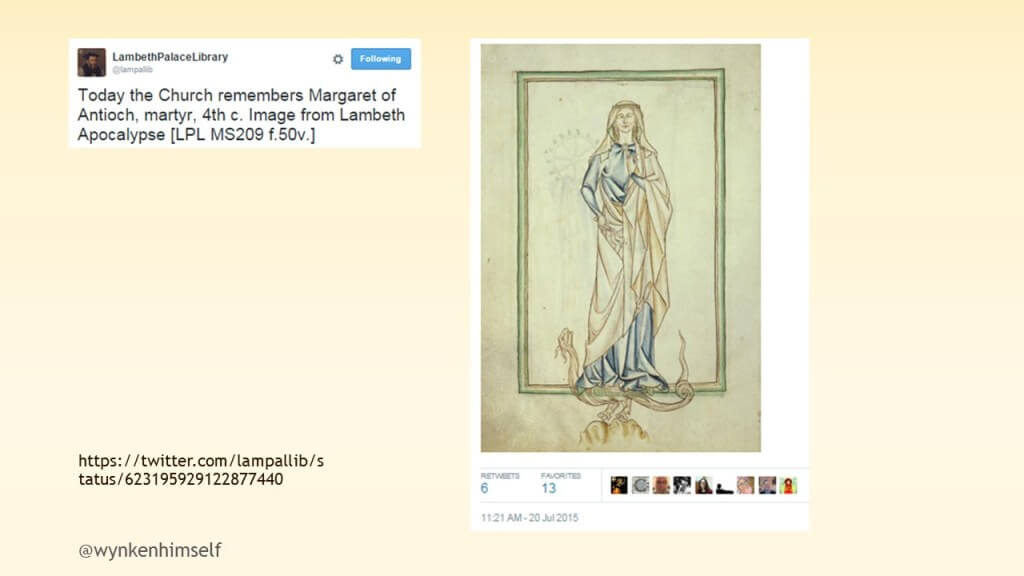

Lambeth Palace Library’s tweets (despite my criticism of their platform and policies) do a great job of being institutionally on-target, informative, and providing citations.

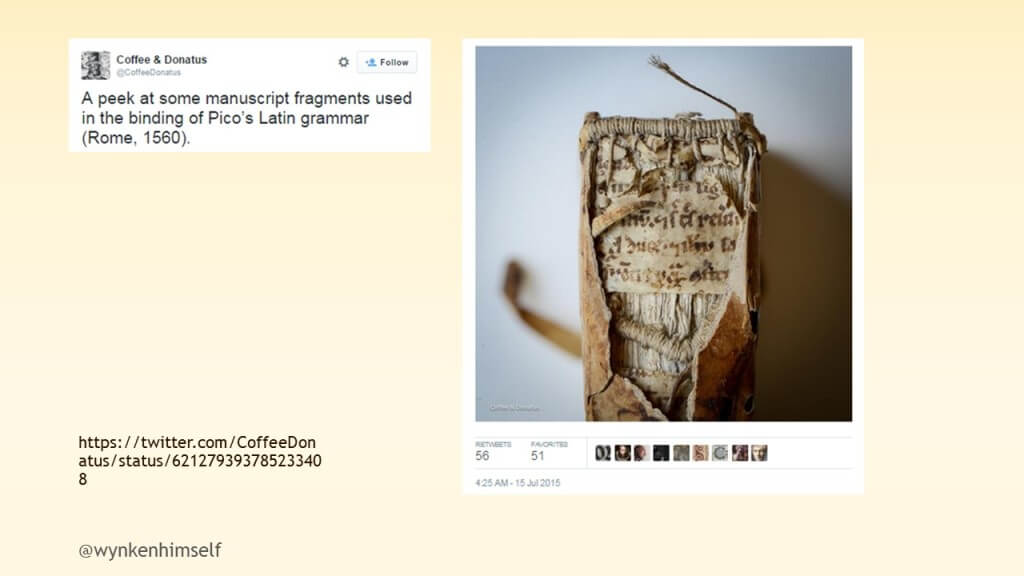

And this tweet from Coffee & Donatus is just gorgeous, along with being informative. (If you follow them, you know that images watermarked Coffee & Donatus are from private collections, so the lack of an institutional citation here is actually appropriate.)

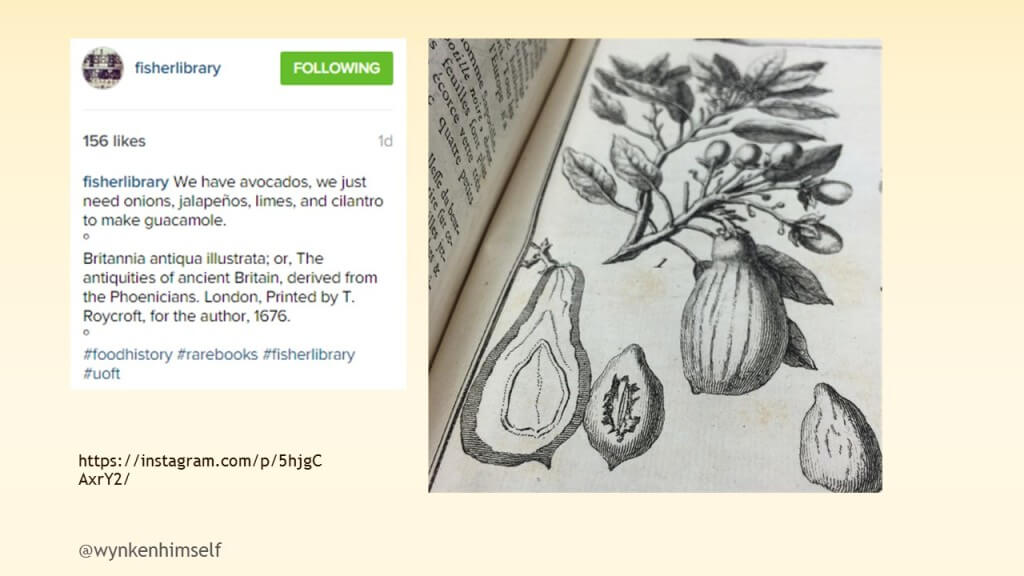

Toronto’s Fisher Library here posts a lovely picture with a caption that is both funny and informative. (They’re one of my favorite library Instagram accounts—if you’re curious about what a special collections library can do with Instagram, I recommend following them.)

The tension between wanting to be funny and appealing and spending a lot of time on things that aren’t informative is rampant in the current obsession with book gifs. This gif of a children’s book illustration shows what I mean—what does the animation in the gif add to this other than being eye candy? Is it a useful expenditure of time and effort? I hope the person who made this had a great time, but I also hope that an institution would think about whether the investment of resources in this type of activity meets their institutional goals. At least the link in the tumblr brings you to the full digitization of this book so you can find out more about it. But Southern Miss claims that this digitization is under their copyright and you need their permission to do anything with it. (According to Corel, they’re wrong.)

Gifs can definitely be useful. This, from Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s special collections, does a great job of showing how this artist’s book works—it would be much harder to explain in words or to show in a series of static pictures the experience of reading this book about Golda Meier.

This, from the University of Iowa, is even better—by creating a gif, they’ve recreated the experience of using this book in a way that you simply couldn’t do with the physical object anymore. It’s a great example of how gifs can allow us insight into books that are entertaining and informative.

So, when it’s so easy to use twitter and social media for laughs, why would you want to use it for anything else anyway? Is it possible that it’s more than LOLs?

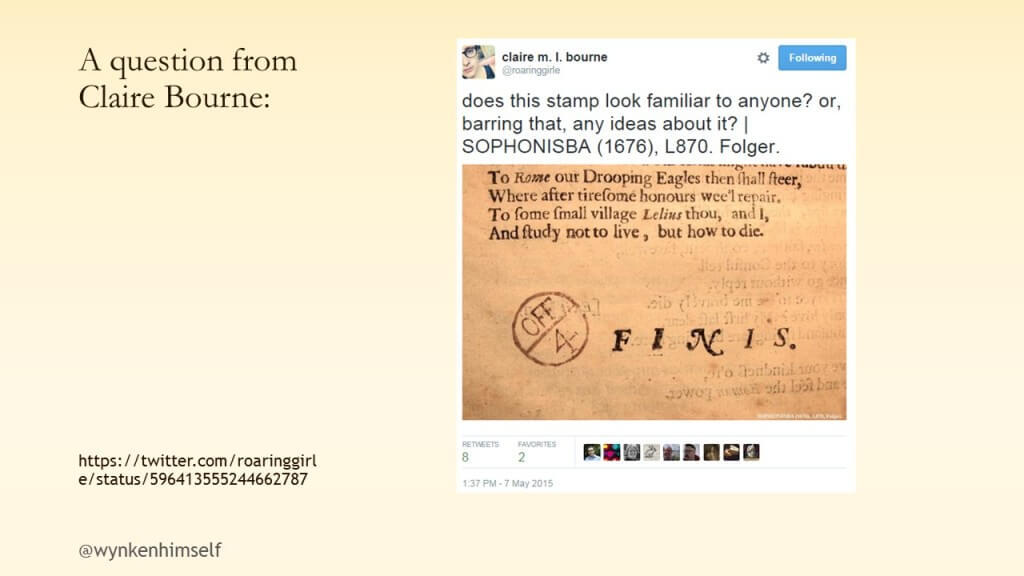

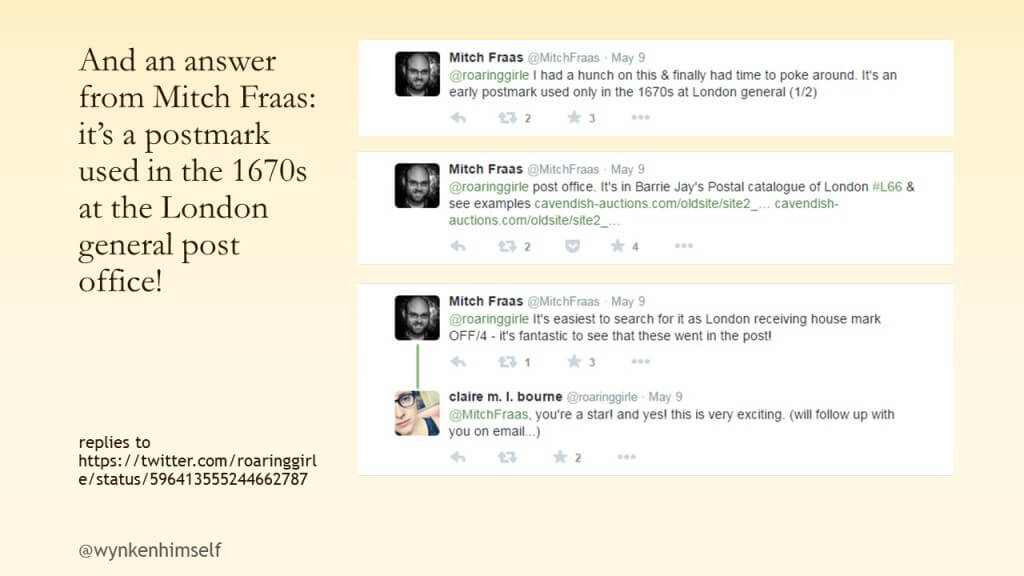

Here’s a quick example of its value from a researcher familiar to the Rare Book School community. Claire Bourne came across an unfamiliar stamp in a 17th-century playbook. So she snapped a picture of it (thanks to the Folger’s self-service photography policy) and turned to Twitter for help in identifying it.

Mitch Fraas, a curator at Penn, saw her tweet and identified it—a postmark from the 1670s—and shared further resources for researching it. Not shown here is that this conversation was joined by another early modernist, for whom it sparked new questions about how playbooks were circulated. By conducting this reference query in public, not only did a researcher have her question answered, it opened up new possible avenues for exploration for others. That’s a pretty powerful reference desk.

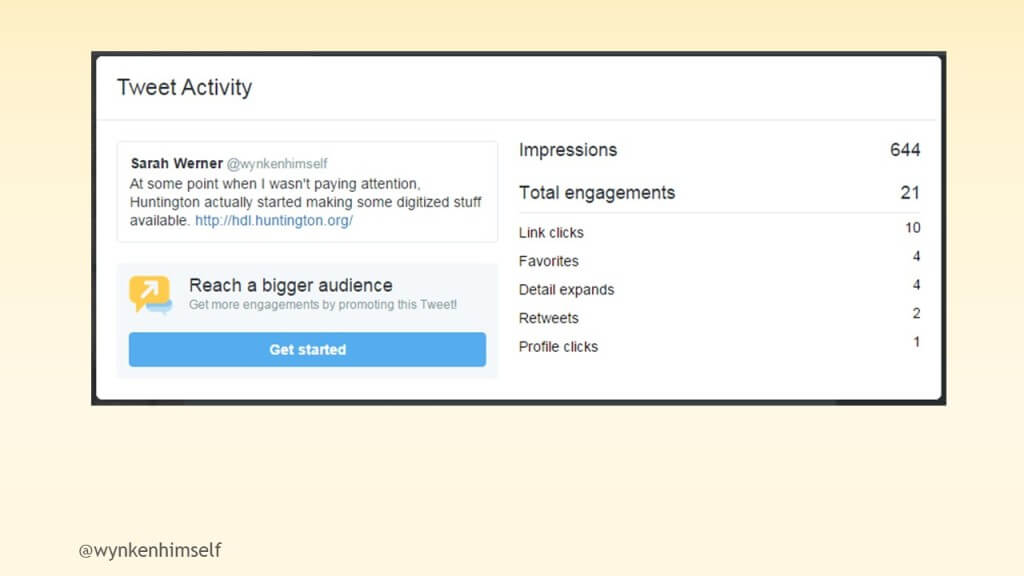

So far we’ve learned to kill special collections by locking down their images and by treating it as a source of jokes and pretty pictures. Now we come to the third important aspect of killing special collections with social media: focus your energies on counting things that can be enumerated.

Social media makes it ridiculously easy to count the popularity of your post—the number of clicks, faves, RTs, …

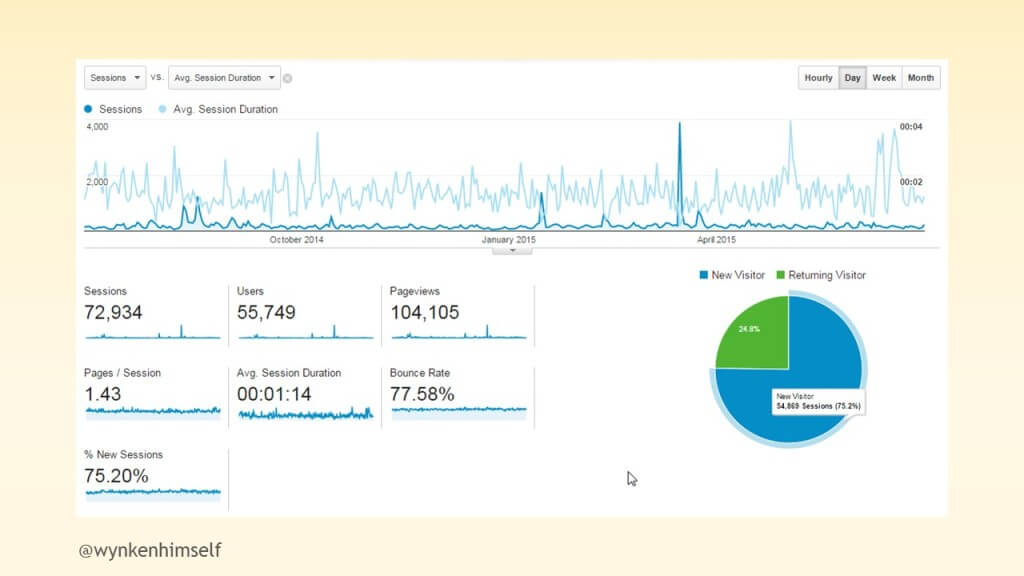

… page views, sessions, the number of new or returning visitors …

… how many likes and comments are on every post we share. The social aspect of social media revolves around the idea that numbers count and that we want as many eyes in front of our content as possible. It’s not just that finding these stats is easy, but that the ease of counting popularity is addictive.

But is there such a thing as too much counting? Is it healthy for us to be chasing those hits? Does counting the countable actually move us closer to what’s good for special collections?

It’s easy to be on social media because other special collections are doing it. It’s easy to count your success by the measurements that your PR folks use. But it’s also easy to find yourself overwhelmed by those metrics, by the need to obsessively count and report. And their goals aren’t necessarily our goals. Not all PR is good PR, especially when it comes at the price of dedicating staff time and budget lines to increasing popularity at the expense of other activities.

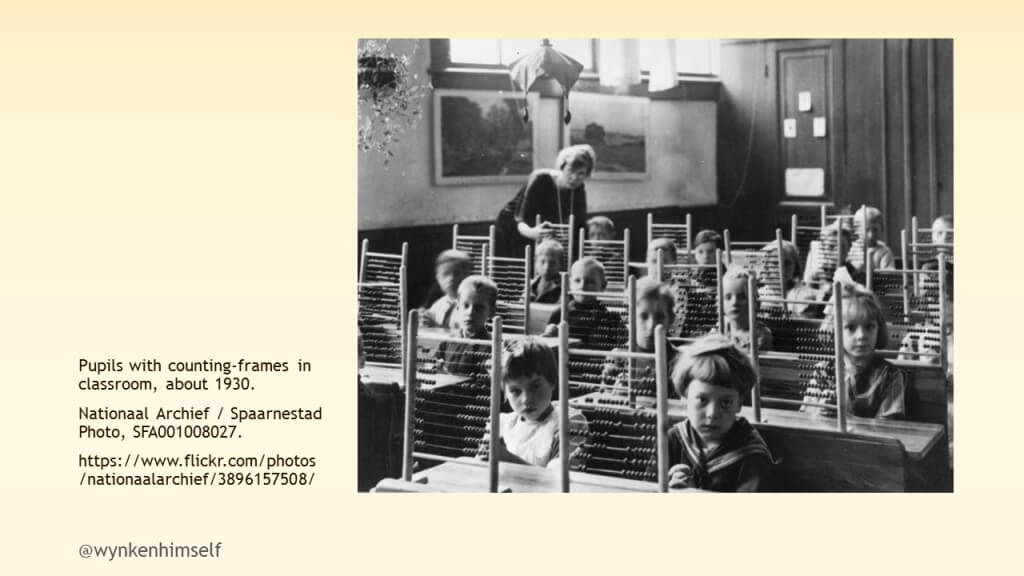

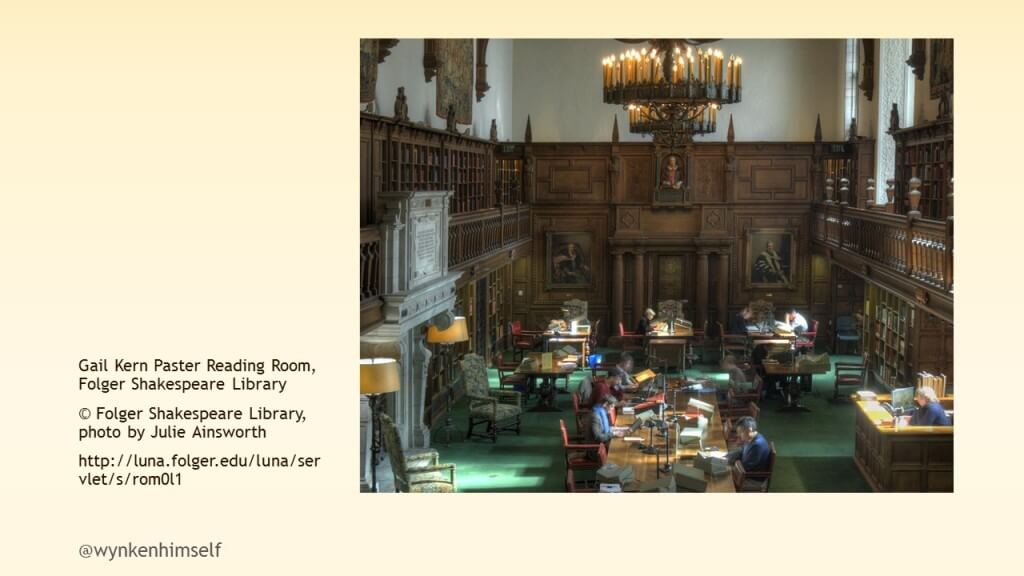

Rather than starting with how popular accounts are, start with asking what your goals are for social media? Is it to bring people into your reading rooms?

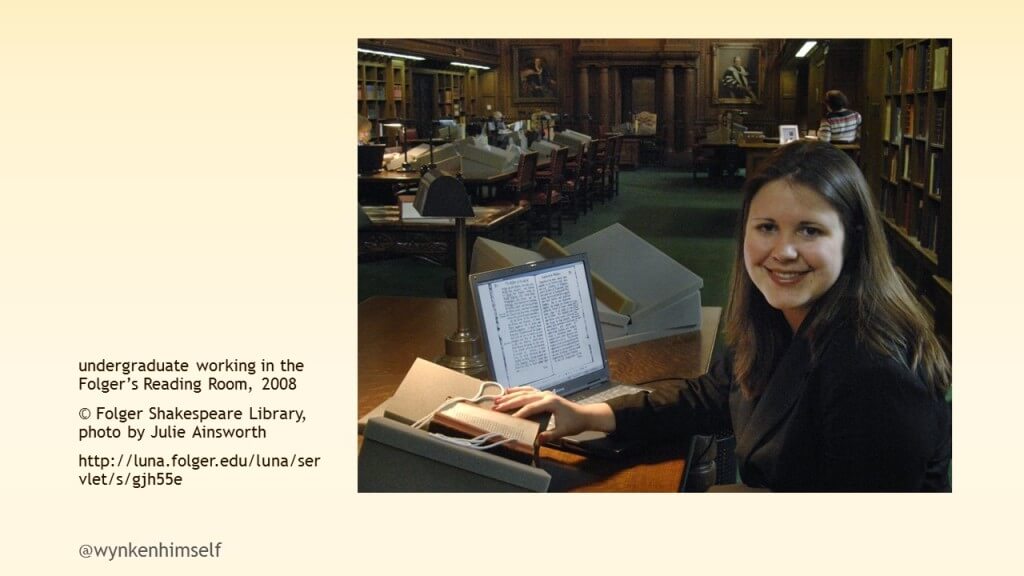

Is it to bring targeted groups of readers into your collections? (Shown here is a participant in the Folger’s former undergraduate program.)

Do you want to give your readers a peek into what goes on behind vault doors in the hopes of sparking their interest in what they don’t normally see?

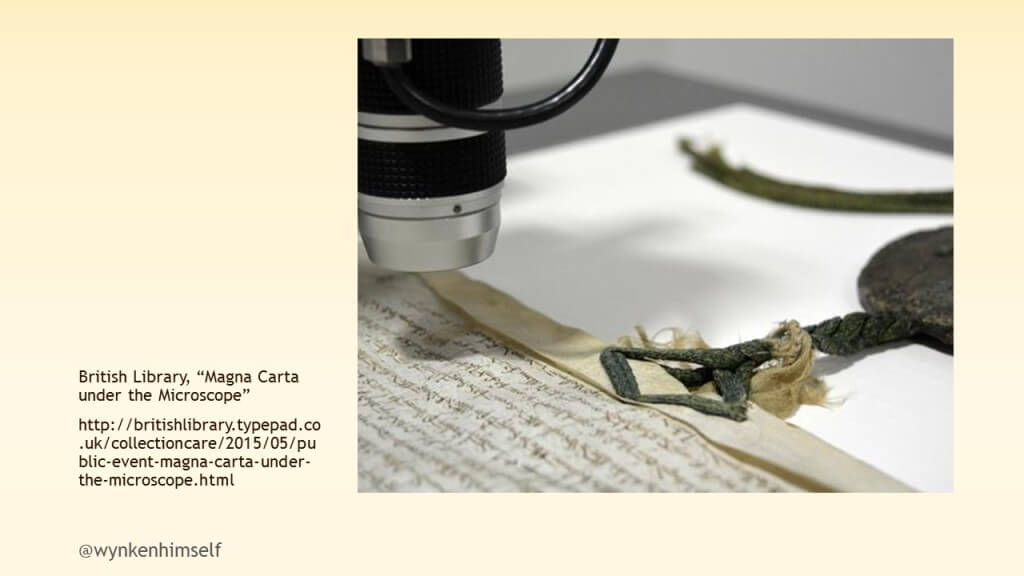

Do you want to illuminate the work done by conservators and perhaps inspire a better appreciation for the handling of rare materials?

Do you want to introduce staff so that readers will feel more comfortable consulting them? (Anyone who has worked a reference desk knows that readers can be weirdly reluctant to ask for assistance.) But perhaps Daryl’s familiarity makes patrons of the special collections at St Andrews readier to seek him out.

Do you want to alert people to new resources or to engage their help in creating them?

All of these are important goals. None of them are incompatible with high page counts and faves. But they’re not necessarily aligned with them, either. A post that gets only 300 views might not be hugely popular, but it could be hugely helpful for the 300 viewers who learn more about an obscure part of your collection.

Special collections are full of objects that are unique and unfamiliar and, frankly, often odd in the modern world. It’s part of what makes special collections special. They’re not places defined by popularity, nor should they be. But they are places with huge riches to offer, whether to scholars or to the general public. And if we want special collections to continue to be places that are valued and accessible well into the future, we need to make sure that they are places that bring people in today, whether in person or through social media.

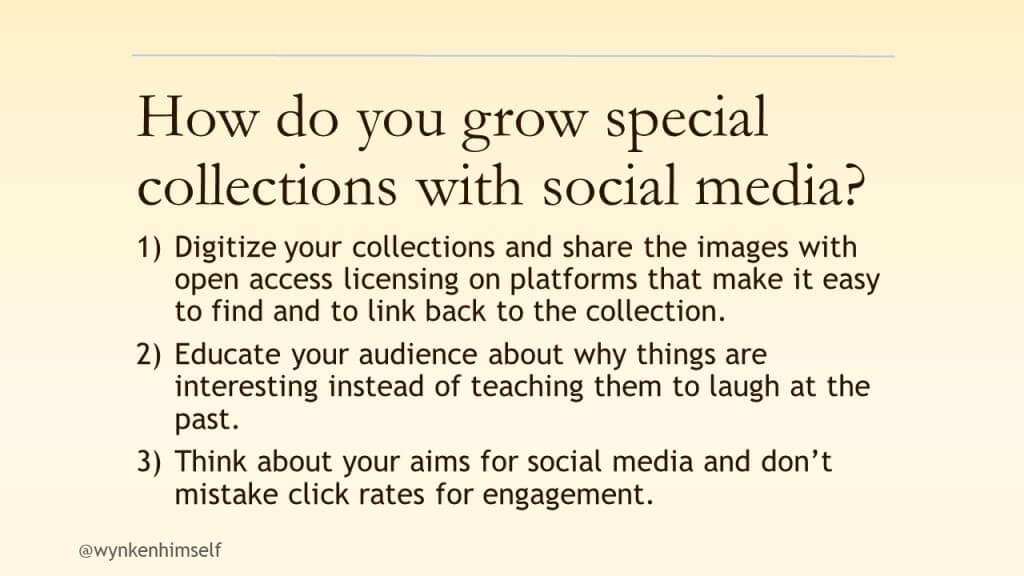

So I’ll end with three easy steps you can take, as librarians and researchers, to help special collections grow by using social media: 1) Digitize with open access licensing and easy-to-use platforms; 2) Teach your audience to think about the past instead of laughing at the past; 3) Choose your aims carefully and don’t confuse popularity with engagement.

.@wynkenhimself’s How to Destroy Special Collections with Social Media is a must-read: http://t.co/3iJcVFXDqW Also I liked the pictures.

Thought-provoking work on social media and special collections from @wynkenhimself: http://t.co/lOMx0rLNEb

I had just listened to this lecture on the RBS site earlier today and enjoyed it. Thank you for posting the images as they have now enhanced to experience.

Hi Sarah this is so interesting, and relates to a project I’m working on at the Hocken Collections in Dunedin, New Zealand. The question of use (or otherwise) of primary sources/archival material on Wikipedia is one of the big ones for us, also. Thanks.

A very good post about the uses of MS images in social media by Sarah Werner: http://t.co/rNJPNM2WKN

Yes! Hurrah! Hear Hear! And a million times thank-you to @wynkenhimself http://t.co/vA2XGS20RG

While I’m supportive of institutions making their images public, you need to recognise that doing so is not free. While larger public institutions are funded to do so, many smaller organisations are not, and indeed derive a significant part of their funding from reproduction fees. Some of these have a sliding scale so that personal use is free or cheap, but fees for publication in various media are greater. Organisations also have an interesting in controlling the information that accompanies their images, and limiting reproduction rights and specifiying the captions that accompany images is one of doing that. You only need to look at Pinterest to see the levels of misinformation that can accrue when images travel independently of authoritative information.

Hi, Sarah. You’re right that funding is a source of concern for many institutions–small and large, I’d say–and in an age of decreased government funding in many places, it’s an important concern. But there are ways to balance making images openly available and keeping your ledgers in the black. Institutions could charge for the labor involved in fulfilling requests, whether taking new images or delivering high-resolution, publication-ready images. And it’s helpful to remember the costs of charging for images: every request that comes in requires both staff time in answering it and lost opportunity time for other work that could be done. This is something we talked about in the Q&A fairly extensively: labor costs and opportunity costs often get left out of the picture when we talk about revenue from images, but neither are inconsequential.

As for wanting to control the information associated with images as they circulate, I’d certainly agree that this is paramount for cultural heritage organizations. And we could point to Pinterest and Tumblr and lots of other social media as places where that information can be in danger of going missing. But I’d also point to those places as evidence of why it’s important for libraries and museums to make their collections available: people are already circulating those images whether you want them to or not. If you make it easy for them to attach metadata to an image, that metadata will travel with it. (Pinterest actually makes it super easy. Take my embroidered bindings board as an example: everything that I’ve pinned from a library links back to its source automatically. For the images I’ve pinned from online collections using Pinterest’s handy “pin it” browser button, like this lovely one, it’s super easy to see all the context the V&A provides for it. Sharing information widely is going to be a better long-term strategy than limiting access to it.

How to destroy special collections with social media. Un bibliothécaire ironique, comme il en manque trop! http://t.co/b8idG7DARK

How to destroy special collections with social media http://t.co/4S74Rt8JjW comm: http://t.co/kNenHyy0S6

Great stuff from @wynkenhimself: how to destroy special collections with social media in 3 easy steps http://t.co/5KTK7D92Oi

This is so good. http://t.co/rjL2E2v2Kb

after http://t.co/c1oysXbTSA yesterday, another mandatory reading: https://t.co/zQZHs4okQu /via hn

Although slightly disagree w/collex gifs value | how 2 destroy special collections w/ social media http://t.co/NFPgR3JP7H via @wynkenhimself

Interesting article, but it is completely devoid of any consideration of the complexities of copyright laws, and of the often exorbitant costs associated with establishing ownership and reproduction rights. There is a passing reference to the institutional costs of digitization projects, but even this glosses over the substantial costs in both personnel and equipment, and ignores completely the notion of risk to fragile items. Discoverability and access are fine goals, and are in fact an essential library value, but when special collections are involved, those goals are part of vastly complicated situations. Chastising librarians is not an effective way to address these issues, as the real bogeymen here are the legislators and funding bodies.

Of course things are complicated! But they’re not always complicated. Many special collections take care of works for which there are no questions over copyright: a 1585 psalter? Well out of copyright. That’s not even something that has to be vetted. An early 20th-century manuscript? Yes, more complicated, but I would again point to the Ransom Center as an institution that is working through those questions in ways that don’t prohibit access.

As for risk, no one would ever advocate for imaging items that would be damaged in the process. But there are risks to not imaging items and costs to not imaging items, and that is what I focus on here.

It’s important to remember that just because an individual or organization asserts copyright over an item or an image of an item doesn’t mean that they actually possess copyright. It’s hard to imagine a situation in which a medieval text is not in the public domain, and simply taking an image of a public domain text or image does not conjure up a new claim on copyright unless that image is somehow transformative. So the Henry Ransom Center’s approach to this issue is not just the scholar-friendly thing to do, it also reflects a realistic understanding of the Center’s relationship to its collections.

You mention how so many institutions claim copyright ownership on items in their collection. These claims are false and designed to scare people away because there is no legal basis for copyright ownership of anything over 100 years old.

Both of you, Adrian and mafi, make a good point: just because someone claims copyright over something doesn’t mean that they hold copyright over it. The term that open access advocates tend to use for this is “copyfraud.” And it’s a problem–it’s a hurdle for anyone who wants to publish this images, since many publishers balk at anything that might possibly cause problems for them. It’s also true that different jurisdictions have different rules about what constitutes a copyrightable image. Although I think Corel is pretty clear in establishing guidelines for the United States, other countries hold that reproductions can be copyrighted. (There’s a big difference, of course, between can and should.)

Grischka Petri’s recent article on “The Public Domain vs. the Museum” offers an excellent overview and discussion of copyright law as it applies to photographic reproductions in the US as well as the UK and EU.

hot on the heels of @wynkenhimself’s call to citation arms (http://t.co/1U4qq2Lex2), I suggest how to cite EEBOTCP http://t.co/83oooHY8Y6

Hi Sarah,

Love this presentation and all of your shared thoughts! Your first lesson is particularly relevant to a storied library in our midst which is presenting our community with a special challenge/problem. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the Phillips Library–I tried to lay the issue out as best as I could here: https://streetsofsalem.com/2017/08/31/losing-our-history/

I just don’t know enough about the situation to feel comfortable commenting on it. I will say that it’s not feasible (or necessarily desirable) for a library to digitize all of its holdings—it’s expensive and time consuming, and most libraries and archives haven’t even been able to catalog all their collections.

Of course. And thanks again for sharing this insightful presentation.