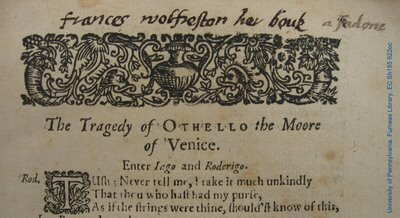

Some time ago, you might recall, I had a bit of a fascination with Frances Wolfreston. (I know, and I totally agree: what’s not to be fascinated by?) From those posts came a lovely missive out of the blue–a colleague at Penn sent an email telling me that they also have one of her books:

Right there at the top of the first page of the text is that familiar inscription, “frances wolfreston her bouk,” but added onto this, in the same hand but a now fainter ink, is something even better: “a sad one.” The book in question is Othello (in this case, the 1655 edition, otherwise known as Q3, or the third quarto). I love the personalization of the inscription–we’ve seen Wolfreston inscribe her name in other books, but it’s not as often that we come across her commentary. And as commentary goes, this note was a productive one for me. The story of Othello is certainly a sad one. But is it a sad book?

Back when I used to teach plays to undergraduates, they would often refer to “the book” as in, “My favorite moment in this book was when the Duchess thought she was holding Ferdinand’s chopped-off hand!” My response was always to insist that the play isn’t a book! and that to conceive of that moment as happening in a book instead of on stage was to fundamentally misunderstand what was happening and how it was made it happen. My perspective then was as a performance scholar: books are objects that you read and they work differently than plays. We might read plays–and with some plays, such as early modern drama, we read them obsessively and too often never watch them nor imagine them performatively–but plays work differently on stage and any good play draws on techniques that make meaning only in performance.

In that sense, Othello is not a book. It’s a play. On the other hand, we do often use the word “book” to refer not to a specific book but to mean a more general story. When I ask my friends, “Have you read any good books recently?” very rarely am I interested in whether or not they have a specific physical object in mind; usually I’m wondering whether or not they have a story to recommend to me (and too often, they don’t!). In this fashion, describing Othello as a sad book is entirely accurate. It is sad. (And infuriating.)

But Wolfreston’s inscription makes me wonder (again) about the ways in which the physical form of books affect how we read plays. How does a playbook differ from a play performance? And how might a playbook represent performance through its mise-en-page?

One obvious place to start thinking about this question is stage directions, a particularly glaring occasion when stage action meets the printed page. I don’t think we always pay a lot of attention to stage directions other than to sometimes mock them for what editors are suggesting or to criticize them for their incompleteness (indicating entrances but no exits, for instance, are a common feature of early modern English playbooks). But while the content of stage directions certainly matter, so does the way in which they are presented on the page.

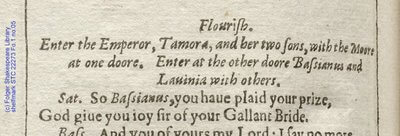

Consider this stage direction from the 1623 Folio Titus Andronicus:

It looks, I think, pretty familiar (zoomable image). The text is centered and italicized (thus differentiating it–as the speech prefixes are also set off–from the spoken text). This is a pretty detailed direction, indicating the main characters in the action (that “with others” is entirely typical) and, unusually, indicating the precise location through which the characters should be entering: one door and the other door. You might want to note that this direction mixes terms: characters are referred to as within the fiction of the story (the direction uses character names, not actor names) but the location refers to theatrical location (the upstage doors to the tiring house). But that, too, isn’t unusual–it’s no different than the directions for characters to appear “aloft” or for sounds to happen “within.”

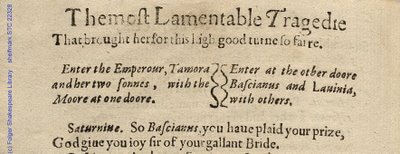

So that’s a typical stage direction. But consider how this moment is represented in the 1594 quarto edition of the play:

It’s the same text (zoomable). But here the layout is noticeably atypical, with the two entrances represented on the page akin to how the blocking would have been on stage: one group on one side, the other group on the other side, the face-off of the brothers indicated with the face-off of the brackets. We don’t usually see stage directions like this. Jonathan Bate’s 1995 edition for the Arden3 series does reproduce the layout of the quarto direction, but most editions do not. And why not? I would assume both that it does not seem important to the editor and that its atypicalness makes editors wary. Familiarity might breed contempt, but usually it breeds comfort. A stage direction that we can read over without dwelling on allows readers to focus on the dialogue–the part of the play that scholars (and general readers) usually prioritize.

My point in comparing these two examples is to highlight the ways in which our habitual sense of what a stage direction looks like obscures other possibilities for how we might think of the printed playbook as conveying–or being capable of conveying–performance practices. If this sort of opposing entrances could be represented in this way, what other possibilities are out there, ignored by modern editors and scholars?

There’s a lot more to be said on the issues I’ve raised here, including the history of the 1594 Titus (the sole existing copy of which is at the Folger; see the catalogue record for more details) and more thoughts on how we read printed plays. I’ll follow up this most with some more along these lines. But in the meantime, if you know of any examples of early printed drama–or, heck, even later printed drama–that seems to you to be doing something different with the interface between print and performance, I would love to hear about it!

And last, some very necessary additional credits and information:

Thanks to Peter Stallybrass for taking and sending on the photo of Wolfreston’s Othello to me. You can see this book at the University of Pennsylvania’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library‘s Furness Collection (shelfmark EC Sh155 622oc). If you haven’t encountered it before, Penn has a lovely rare books library with lovely librarians (and I don’t just say this because of all the hours I spent in the air-conditioned sanctuary of Furness). They have a nice online image collection that you can browse as well as a digital text and image collection that has some great teaching tools.

As for the plays I’ve mentioned, I have to confess that very rarely did my students identify Ferdinand’s severed hand as their favorite moment. If you have no idea what I’m talking about, get thee to Duchess of Malfi immediately! It’s only now that I’m realizing that I chose a theme of lopped-off body parts to connect my examples in this post (okay, not so much Othello, but still…). And if you don’t know what that refers to, get thee to Titus Andronicus immediately! If you’ve downloaded the software for the Folger’s digital collection (as opposed to using it through a browser), you can pull up the entire quarto of the play as a digital book (do a shelfmark search for STC 22328). You can also do the same for the complete folio (shelfmark STC 22273 Fo.1 no.05), though you can also access the digital book through the Hamnet catalogue entry. Then you can read and zoom the entire play to your heart’s content!

>Hi Sarah,In a much later period, the plays of G. B. Shaw and J. M. Barrie raise fascinating ideas about the interplay between performed “play” and printed “book.”G. B. Shaw understood the printed text of the play to be a cultural product in its own right and maintained very tight control over its production. Some results of this control include:- very long written prefaces to many of his plays (sometimes as long as the text of the play itself)- very particular ideas about typeface and margin (e.g., quite large margins consistent across printed “books” of many of his plays, and rather than underlining or italics for emphasis, using extra spaces between letters of a word, s o r t o f l i k e t h i s.)- absence of apostrophes (i.e., dont rather than don’t)- lengthy and detailed stage directions (See Katherine E. Kelly, “Imprinting the Stage: Shaw and the Publishing Trade, 1883-1903,” in _The Cambridge Companion to George Bernard Shaw_ for a much more detailed and smarter discussion of these things than I can give.)The stage directions of Shaw are especially intriguing in relationship to performance, as they are so detailed and specific as to be impossible to really convey in a staged performance (although I imagine very useful for directors and actors working on the performance).It is fascinating to see the different ways directors will use these directions, to at least give some sense of them to the audience. I have seen:- “voice-over” or narration (either recorded or spoken by an actor) of (some part of) stage directions- writing of some part of stage direction text on the scenery- printing of some part of stage direction in the printed programmeI don’t know if J. M. Barrie was so intimately involvement with the details of printing of his plays, but the text of his plays clearly “want” to be read and not only performed. If anything, his stage directions are even more detailed and more playful than Shaw’s.For these two playwrights, I always feel like there can’t be a single “complete” mode of experiencing the text. Typically I will try to read the “book” of the play as soon as possible after seeing the play, to try to bring together the dual experience of seeing a theatrical and reading the text (with its “supplemental” materials).

>Thanks, Darryl–this is really helpful. I was aware of Shaw in a general sense–certainly those long prefaces and those very detailed stage directions and settings suggest to me a desire to turn playscript into something that is readable in ways that are familiar to, say, novel readers. I haven’t looked at the originals, though, so am glad to hear about those details.As for Barrie, I know nothing about his plays (or even, indeed, about any of his work), so that’s a helpful suggestion, too.One of the books that has been sitting unread for too long on my shelf is W.B. Worthen’s Print and the Poetics of Modern Drama. Shaw shows up in Worthen’s book, along with a host of others, including Anna Deveare Smith and Suzan-Lori Parks. I clearly need to move that book to the top of my pile. And, I think, I need to take this as an excuse to go to theatre more often…

>Cary Mazur @ Penn was doing some interesting things with texts and performance a few years ago. He taught a class on early modern plays, modern texts, and contemporary readers (or something like that). He may be worth looking up!

>That’s a more apt suggestion that you know, Tim–Cary’s an old friend and it’s an ongoing topic of conversation between us!

>I do remember having difficulty getting students to attend to stage directions. “Oh, I never read those,” someone would always say blithely. Just finished reading Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun which is part play, part novel. Fascinating but impossible to stage, I’d imagine, unless you just skipped the novel-parts, which would kind of defeat the purpose.

Great post! It raises some interesting questions for me, too, about household forms of drama and their relationship to material textuality (thinking particularly about closet drama and masque). For CD, the text preexists any performance — and the text generates opportunities for women to perform privately in the closets at home, alone or with friends. For M, the text post-dates the performance and seeks to recreate an entertainment that was only spoken in part and largely involved spectacle; its creation as text documents only in part the massive performance and belies the number of contributors (becoming, for example, Ben Jonson’s Masque of Queenes). So many good ideas to wrap the mind around…and hopefully guide students through!

mary smith should meet frances wolfreston (see http://t.co/NrQQ02Q9Gp). | OTHELLO (1695), S2942 (Copy 3), Folger. http://t.co/eQ8eLKWMZ5