So after my last post, I’ve been thinking about what it means to make digital early modern books available in the sort of democratic access that Darnton hopes for in an Digital Republic of Learning. My final point, in that post, was that when my students are first confronted with early English books, they don’t know how to make sense of them.

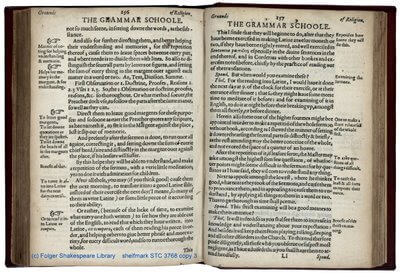

Here’s one example of the sort of book that might perplex them:

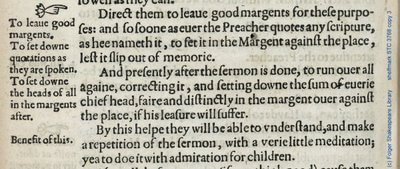

Just looking at the page opening brings up some of the details that estrange us from early books: the catchwords at the bottom of the page, the signature marks, the fists and marginal comments. None of those are details that we are used to seeing in how today’s books are laid out. And then there’s the text:

This is a pretty straightforward and easy-to-read example. But even so, there are the long s’s that look like f’s, the non-standardized spelling, the interchangeable (by modern standards) u’s and v’s and i’s and j’s. (This image is from John Brinsley’s 1612 Ludus literarius: or, the grammar schoole, an appropriate choice, I thought, for thinking about learning and the connections between learning and reading and writing. Don’t forget to note your scripture in the margins! A zoomable image of the page opening is here–although you’ll need to have your pop-up blocker turned off–and the catalogue listing is here.)

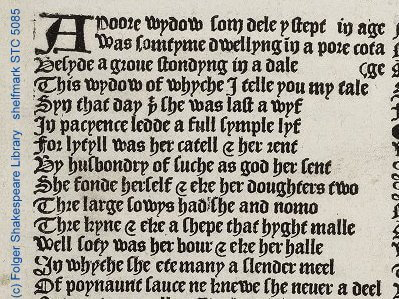

What about this for being accessible?

That’s not as easy to read. It’s not simply that it is in a gothic font, although that doesn’t help–it’s not a font we’re used to today. But there are different letter forms even in that font: there are two different forms of “r,” for instance, as seen in the last two words in the seventh line. There are also different spellings than we are familiar with, not to mention the different vocabulary. There’s also the use of abbreviations, such as the thorn (what we would describe as a “y”) with a superscript “t” in the fifth line. And then there’s the second line which is too long to fit on one line, and so the final letters spill over onto the third line, marked off with the bracket.

What is this text? It’s the start of the Nun’s Priest’s Tale, from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, here shown in an edition printed by Wynken de Worde (my man!) in 1498. Here’s a transcription (I have not regularized u/v or made any other changes):

A poore wydow somdele ystept in age

Was somtyme dwellyng in a pore cotage

Besyde a groue stondyng in a dale

This wydow of whyche I telle you my tale

Syn that day that she was last a wyf

In pacyence ledde a full symple lyf

For lytyll was her catell & her rent

By husbondry of suche as god her sent

She fonde herself & eke her doughters two

Thre large sowys had she and nomo

Thre kyne & eke a shepe that hyght malle

Well soty was her bour & eke her halle

In whyche she ete many a slender meel

Of poynaunt sauce ne knewe she neuer a deel

Oh, yeah, there’s one other difficulty in reading this: no punctuation!

Those of you who know this text might notice, too, that it doesn’t match up exactly with today’s standard texts, and I’m not talking about how the spelling changes from one text to the next. At some point in the transmission from the surviving manuscripts of Canterbury Tales to this printed text, some of the words have changed (is the cottage narrow or poor?). Such are the joys of working with early texts. And I mean that seriously–I love that texts change as we transmit them.

So does putting early English books online make them accessible? My Chaucer example might be a bit loaded–part of what makes that book hard to read is Chaucer’s language, which is distant from ours in ways that are assisted by glosses or teachers (although I do think that it’s possible to understand the Tales without such aids, if you read patiently). But that is what early printed Chaucer looks like. And my first example doesn’t have that problem–there are no big vocabulary obstacles and no strange printed letter forms to confuse us. But it still holds itself apart from us through the way that it appears.

I am certainly not suggesting that early modern books should not be made accessible through digital surrogates. (And there’s a whole other post to be done on what digitization cannot do for us.) But it is helpful, I think, to remember that early modern books are not necessarily ever accessible without an apparatus that has been generated either in the classroom or through other forms of scholarly attention and intervention.

I don’t think that Darnton doesn’t know this. He certainly does. But in the discussion of what digitization means, I find it helpful to remember that access does not mean understanding. And looking back at early printed books can help us remember the ways in which texts and learning and reading are not always easily aligned.

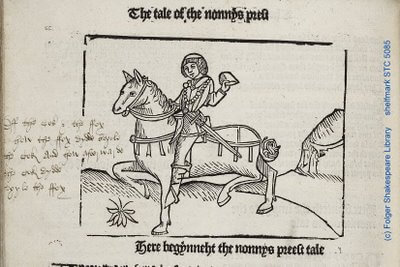

And now to close with something pretty! Here’s the lovely woodcut illustration and the marginal annotation summarizing the tale that starts things off (zoomable image of the page opening here; catalogue entry here).

>I read these past two postings with great interest. Your caveat (in response to Darnton) that “access does not mean understanding” is well taken. Perhaps the alterity or “foreign-ness” of early printed books simply highlights that reading *never* occurs in a vacuum; even if you are face-to-face with a text as a solitary reader you can’t make any sense of it unless you’ve gained (through previous reading, your own experience, classroom settings, etc.) some idea of its context, aims, conventions, etc.What I appreciate about digitalization projects like those at the Folger is precisely the wider access they provide – a digital image allows you not only to read a text but to *look at it* as well, picking up on what it transmits in addition to its “content.”For example, the catalog entry for this wonderful final image notes there’s “marginalia” at this point in the NPT – but it does not say any more about what that actually entails. It’s only when you gain access to the text (see the physical layout of the page) that you get some sense of how an early reader engages with the text.It does strike me as very interesting how this reader “frames” the text to come. At the end of the NPT the narrator claims he’s not just telling a fable about “a cock and a hen” – it’s potentially a philosophical debate, moral allegory, conversation about marital roles, etc. In characterizing the NPT as the tale “of the cok and the fox,” this annotator conditions readers to access this text in a very particular way (as an Aesopian fable) – a narrower reading that largely ignores what the narrator states about the tale itself.

>Thanks for this really thoughtful comment, Jonathan. I do think that digital access (like what the Folger is starting to provide) has the potential to change what sorts of research we can do. Nothing is ever going to replace going to the book itself, but this could potentially make it much easier to sense what books are worth visiting for what purposes. As you point out, the Folger’s catalogue does not mention what sort of annotations are in the book (although the fact that the record reveals the presence of any annotation is itself a huge step up over lots of other catalogues–so big props to the Folger cataloguers for that!). It’s only when we look at the image of the book that we begin to see the ways in which this user shaped how this tale could be understood. (And, as you point out, that starts to get at an interesting exploration of the relationship between user and text.) I do like this as an example of the value of looking at books and digital images, especially after your great additions to my sense of what is going on with it. But not everyone who looks at this is going to be able to do something with it. So here’s the question for those of us who teach these texts and who would like to be teaching books of these texts: to what use can we put these digital images? What sorts of frameworks can we provide to help them be of use to others? And then how do we make sure that these texts and frames are found in order to be used?

>Sad news: the value, I suspect, has little to do with the kind of research you do. This is not at all a criticism of your research or the Humanities more generally, but an attempt to broaden your point of focus. Digitization and redistribution of these works will tend to undermine many academic assumptions of credentialling and merit. It will reduce barriers to access to these documents for non-academic scholars and the lay public… and all sorts of things might happen as a result.I’ve been involved for several years with Distributed Proofreaders (ironically, the site is broken just now), and spent a tangible portion of my time attending and presenting at various Digital Humanities conferences. And yet I keep hearing and reading these concerns about digitization’s inutility in the Practice of Scholarship and Pedagogy.I have to shake my head, because I agree wholeheartedly but wonder why this is discussed. I doubt scanned books will be any use at all in teaching graduate classes or in proper archive-based research projects. They may save some scholars a few disappointments when they finally see the physical object, by showing a “preview” of the thing itself. (But really, what benighted professor would give up their sabbatical junket to a Great Library for archive research?)But the texts you’ve tapped as “challenging” wouldn’t faze the hundred blackletter specialists at Distributed Proofreaders; the marginalia would be sought out as a challenge by a dozen fans—for fun. While they might not talk about it aloud or explicitly, amateur volunteers are doing the required modeling of the document when they’re planning and creating an authoritative transcribed electronic version. It happens as a matter of course.And those thousands of volunteers doing the work at Distributed Proofreaders and allied sites are for the most part nonacademic, or academics from the “wrong” departments, or foreign, or retired. In my experience, none is as ignorant or ham-handed as a canonical undergraduate transcription intern. They are all volunteers, and for the most part personally engaged with the works, and discussing not just the technical aspects of production but their meaning and context.Distributed Proofreaders is a test-case, and is often conflated with the egregious Gutenberg project to which it provides the majority of content. Project Gutenberg is full of junk, I admit. My point is that some folks have nonetheless the skill and interest to focus on just this sort of “difficult” text. And I’ll argue they’ve exceeded the results of any official grant-funded Digital Humanities project.It’s as if the Academy has forgotten all about the antiquaries—the men who actually collected and saved these physical documents in the first place. The ones who published the 18th and 19th century magazines that fill my shelves with interminable discussions of inscriptions and editions and mysteries and local knowledge, and spent their middle-class disposable income having wood engraved reproductions made of their collections, and wrote these pedantic letters on local names, and filled innumerable miscellanies and folklores.Those were poorly-trained folks, by modern standards; mere stamp collectors and dilettantes. But they saved the physical works, because they were either honestly interested in them or found some other social benefit in having them around. In the process they filled the bibliographies of properly trained academic scholars for many decades.Mind you, this isn’t a personal criticism. My point is: the walls of scholarship have coincided with the University’s bounds for a tiny fraction of “scholarship”‘s existence. I can attest—having just paid my $380 annual fee for the privilege of dragging my butt downtown and sitting at a low-grade computer in a campus library so I can swear at the stupid EEBO scans or read JSTOR’s precious license-protected 19th century public domain journals (without being permitted to save or print them)—I can attest there are still real people out here that folks inside the monstery walls who find utility in these scans. :)As I said, I’ve been to too many Digital Humanities conferences through the last few years. I can’t personally put faith in the transformative power of any project now extant, inside or out of the Academy. I have yet to see a well-designed project that opens access to real people, regardless of their authority, and which doesn’t try to recoup some imaginary “cost” by charging for things in the public domain.But… well, let’s just say there are some cultural surprises lined up in the coming years. Not to mention a good deal of utility to be recaptured.

>Tell me, which is easier to read, page images off EEBO, or the transcribed texts created by the text creation partnership? My answer would tend to be the page images: the eye copes with a line of maybe 12 words: the text creation partnership transcripts run maybe 20 words or more across your browser. I get eye-slip all the time. Of course, for the sheer ease of getting a quotation into a document, I tend to read the transcription. But I often think I should revert to the page images.

>Vaguery and DrRoy–thanks to both of you for your thoughtful and thought-producing comments! I’ve been away for the past week, so please accept my apologies for the delay in responding to them. But if you’ll look at my post today, you’ll see that I follow up in part there.

>i think dis is real easy 2 read wanc you no da dffrint lettas, nuns priests tales probly my favrit chaucer, itz ironic approch 2 marital values at da tim iz pricelezz! itz grat hw humor thts 6-700 yers old is stil funy.