I’ve been writing these posts since 2015, and, especially in recent years, I keep asking the same question: what is time anyway? This year is no different. Or, it is different because there are new griefs and fears and time is moving in ways both slow and fast and it slips through my fingers before I know what to do.

Part of this feeling comes from the year’s circumstances. I went to New Zealand in late January, spending three weeks of summer in the middle of winter, and seeing a bit of a place I knew nothing about and that looks so little like most landscapes I know. My oldest spent the summer in California on an internship, the first time in which he’s not lived with me for at least a few months in a year and the startling realization that he might never live with me again. My youngest went off to college, something that I grieved for in advance only to discover that living by myself is actually glorious. And then right at the start of 5784, there was October 7 and its long bloody terrible aftermath, still ongoing without any clear end in sight and with the full-body apocalyptic horror of shouting helplessly at my own communities. And what’s in store for us in the United States in 2024? It looks a lot like repeating mistakes we should have learned from and more horror and dread.

There’s hope in all this if we look, too. That hope is in the ways people have stepped up to care for each other, in how set-in-stone beliefs are maybe slowly shifting. It’s in the joy of seeing my kids grow and become full, caring, active members of the world. The present is so unsettled that the future is even more visibly in flux, and we have a chance to use this moment to build something new. Will we? Maybe? Maybe not? But the promise is in the act of building, not in the having built. We practice, we strive, we look for our prophets, we get up every day and work. It’s hope. It’s tikkun olam.

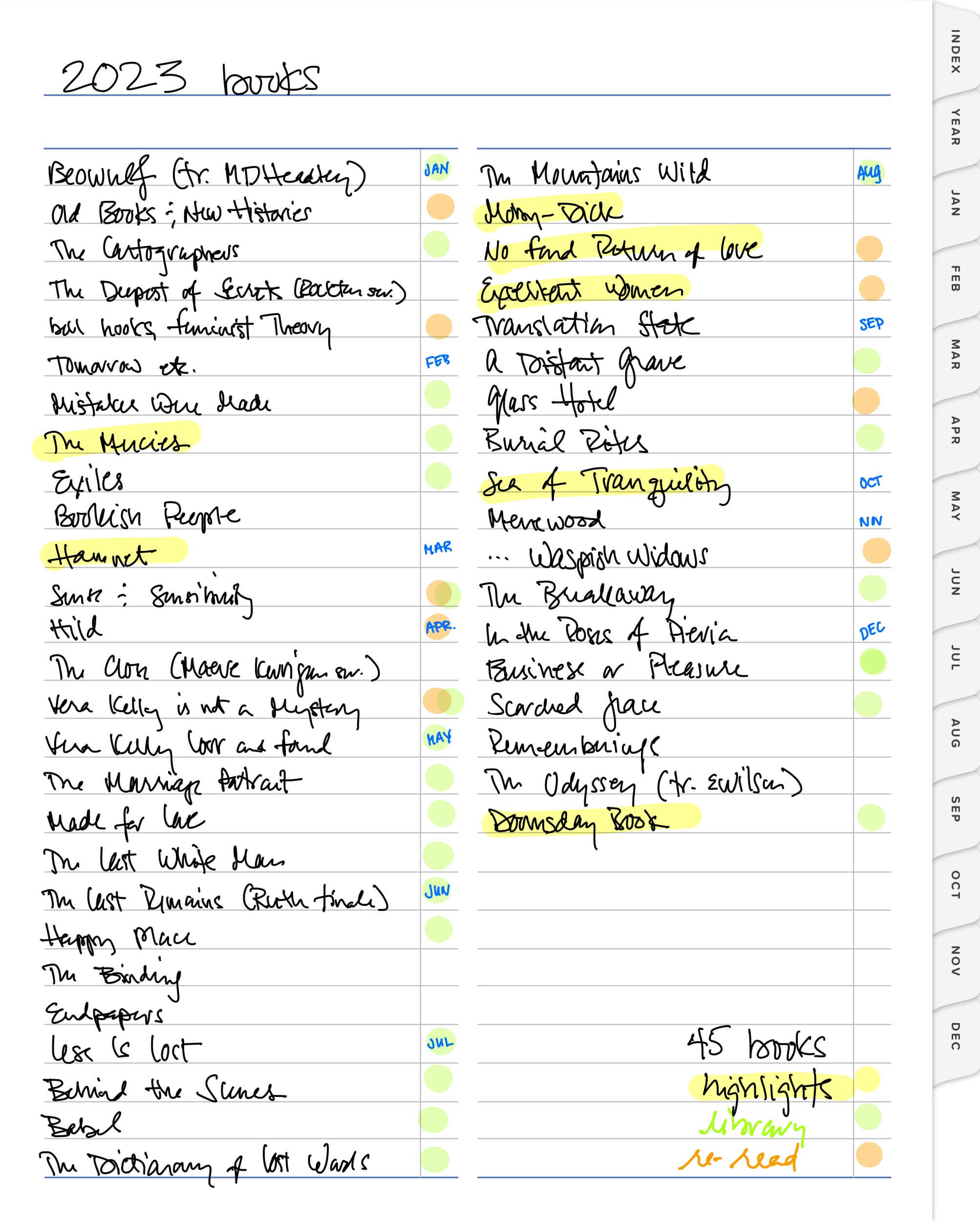

head over to Bookwyrm to see the full list of my 2023 books; I promise it’s not my handwritten scrawl! (to see my reviews, you’ll have to click on the book, and then scroll down to find mine)

The most astonishing book I read this year was Moby-Dick. I picked it up, decades after first having read tidbits of it for comps in grad school, largely because my youngest had read parts of it in high school and because we were headed to New Zealand. I did not expect the sheer shaggy weird excess of it. Yeah, there’s a plot about revenge and destruction. But it’s also about trying to capture the uncapturable by writing a book nearly as massive and detailed as whales themselves. It took me close to eight months to read it, not because it’s actually that long, but because I read it so slowly, usually at night before falling asleep, letting it wash over me. Such destruction humans wrought, all those people devouring whales to light their homes and make their engines go and all the industry that led us to where we are now, having gobbled up so much of our world’s natural bounty that we’re killing the planet. It was a peek back to a moment when we could have done things differently, and Melville felt on the side of whales in this, in the horror of whale bloodshed. He was also on the side of whiteness, without a doubt, but also so excessively so that my 80s lit training makes me want to say that his insistence on the horror of whiteness and yet the superiority of white people comes out in the strangled ways in which he can’t quite articulate why racially white is good. (Please don’t make me be a lit scholar about this; I’m not a 19th-centuryist, I don’t want to be, I just want to read.) Melville was a horrible person in so many ways. And this book is a piece of genius that I can’t quite hold in my mind.

I read other astonishing books both during and after that one. Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet was pure beautiful grief. You know what’s coming and there’s nothing you can do to stop it, just like there’s nothing the characters can do to stop it. It wrecked me. (I tried her Marriage Portrait after this, but I hated it with a passion. It viscerally made me angry when I realized how she was going to get out of the plot she’d created, and I’m still angry now when I think about how she invented someone she could then destroy so that her rich heroine could live ever after. Fuck that.)

And then there were the time travel books. Emily St. John Mandel’s Sea of Tranquility was explicitly about the circles of time and how past and present and future all shift. What’s real? What makes things real? Station Eleven continues to be one of my favorite books, and the ways in which it and Glass Hotel and Sea work together is subtle and important and delightful. There’s grief and loss and yet also there’s hope and a future to build for in all of them.

Connie Willis’s Doomsday Book has more grief and less future in it, and so much pandemic trauma. I’d read the others in the Oxford Time Travel series and so knew what to expect, but also I read this one completely unprepared for the levels of loss in it. I couldn’t stop thinking about how traumatized they all must be, having gone through so much death and fear, and then I couldn’t stop thinking about us today. When are we going to pause to reckon with our pandemic trauma? How are we ever going to heal from the traumas happening in Palestine and Israel? Doomsday Book focuses on faith as the answer and on creating families of choice and need. Is that enough? I don’t believe in a God that swoops down and rescues us, and it’s clear Willis doesn’t either. But my faith as a Reconstructionist Jew teaches me that we can be godly—when we care for each other, we are the holiness that we seek.

Here’s to a future in which we actually choose life, in which we remember our obligation to save a life—not only to not kill but to make possible for everyone to have the chance to flourish, to find the holiness that is in all of us. Our governments might be failing us (they are failing us), but we don’t have to fail each other.

Happy new year.