I’ve just come back from the annual conference for the Rare Books and Manuscripts Section of the Association of College and Research Libraries (more commonly known as RBMS, thank goodness, because that’s a mouthful). I was honored to be asked to be one of the speakers for the plenary on “A Broad and Deep Look at Outreach” and for my talk, I decided to look at how friendly and open the special collections digital landscape is. (Spoiler alert: not as radically open as it could be and should be! I’ve deposited my talk in MLA’s CORE if you’d like to read it, and I will post the link to the audio of the session once RBMS makes it available.)

As part of my exploration, I decided to try searching for facsimiles of early editions of various books—part of what makes the digital landscape so frustrating is that there isn’t a centralized list of what digital facsimiles are out there. If you’re looking for an item that’s held by a specific library, you can look in their digital collection (if they have one and if you can find it and if you can figure out how to search it). But if you’re looking for openly accessible images of a printed book, it’s a lot harder. That’s what I wanted to experience.

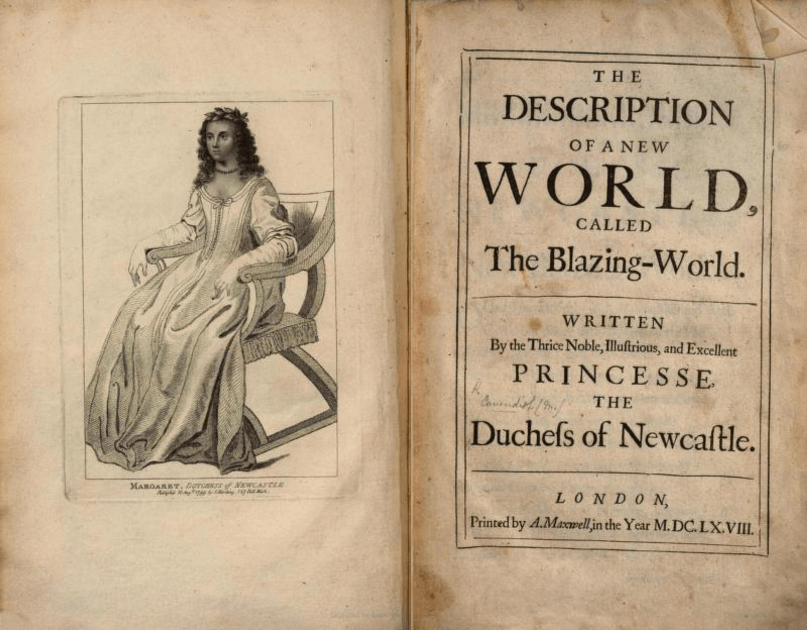

I started with Margaret Cavendish’s Blazing World, a work first printed in 1666 with a second edition following closely upon its heels in 1668. Cavendish is an amazing woman and an important early modern figure; Blazing World is often described as the first work of science fiction, and it can be read as responding to and participating in the scientific conversations of its day. It seemed like a good candidate for digitization: it’s significant in its field, of interest to scholars and potentially to wider audiences.

I wanted to find an open access facsimile of it, so Early English Books Online wasn’t going to do it for me. ((Lots of researchers don’t have access to EEBO, a subscription site that offers subscriptions to institutions, not individuals. I have access through my membership in RSA, and I’m grateful for that every day. If you need to use EEBO and aren’t affiliated with an institution that subscribes, you might want to consider that route; RSA membership is quite cheap and the benefits are great.)) I thought I’d start with the two big aggregators of digital collections, DPLA and Europeana. Neither turned up anything. Because Blazing World was first published with Observations upon experimental philosophy, short title catalogs often list it under that title, so I searched both for “Blazing World” and “Margaret Cavendish.” I did get a bunch of copies of her memoir of her husband, The life of William Cavendish, most of which included her own memoir, A true relation of the birth, life, and breeding of Margaret Cavendish, but not Blazing World. I tried Internet Archive (same results) and Google (ditto). I spent half an hour being frustrated and gave up. Two Cavendish scholars did confirm, when they saw my laments on twitter, that the only facsimile they knew of was on EEBO.

This absence of Blazing World became the rhetorical turn of my RBMS paper, placed alongside the abundance of facsimiles of the First Folio. “16 First Folios, and not a single Blazing World” was my blow against the lack of diversity in what libraries digitize. ((It’s true. We’re up to 16 now, and it is likely to keep growing. This is why I keep a running catalog.)) All those resources spent on Shakespeare, and nothing on Margaret Cavendish. It hit home, based on the nods in the audience and the tweets of the talk. Why do libraries image some books and not others? Is there a strategy behind it? Are they in it to highlight their own collections or to add to the research landscape? Is the First Folio really worth imaging 16 times, when most of those copies do not have any unique features?

And then the shocker: After the talk, I got a message from Mitch Fraas, a friend and colleague at Penn’s library, who shared that he found the 1668 edition of Blazing World on Google Books! I’m delighted it’s there! (I’m also delighted I found out just after my talk and not just before.)

I cannot now recall why I didn’t find it. I don’t think I looked it Google Books. It’s possible that I did look in Google Books but that I searched for “Margaret Cavendish” instead of “Blazing World” (I soon discovered that searches for the latter turned up more false positives than the former). The problem with searching “Margaret Cavendish” in this case is that Google Books’ metadata has this as authored by “A. Maxwell.” Who is A. Maxwell, you ask? He’s the publisher. Why would that happen? I suspect that in the automated process of imaging and OCRing this, the imprint was easier to parse than recognizing the author:

In any case, I didn’t find it and Mitch did, and it’s there! It turns out you can also now find it in the Internet Archive (although there the metadata gives it the title of the 1666 edition, Observations upon experimental philosophy, instead of the correct The Description of a New World, called The Blazing-World).

So what are the lessons here? 16 First Folios, and only 1 Blazing World? That still works, kind of. But the point I’d make here is that searching for facsimiles is hard. That I either didn’t think to look in Google Books or I searched with the wrong terms is all the more evidence of how hard it is. I search for facsimiles a lot! I’m an early modern scholar! And if I struggle to find these things, imagine how hard it would be for our students or for the generally curious reader.

The other point I’d make is that the landscape of what’s digitized is changing all the time. The British Library’s copy of Blazing World was digitized by Google on March 22, 2016. It was uploaded to the Internet Archive on June 24, 2016. I gave my talk on June 23, 2016, and did my intensive searching earlier that week.

That we are constantly adding to digital collections gives me hope: maybe soon the texts I dream of finding will soon appear. Maybe gradually we will create a robust openly accessible collection of early modern books online. But it also drives home to me the importance of thinking about how the decisions of digitization are made and how we present those images. Are they findable? Are they usable? Can we download the images and use them as the public domain works they are? ((I’ve gone on about this before. See Bridgeman v. Corel for why I and the Southern District of New York think so.)) Do we provide any context for what these works are and why they matter? If part of the mission of libraries is not just to collect and to preserve but to educate, how is what we are doing serving that mission in its entirety?

The radical potential of digital tools for special collections is they let everyone use rare books and manuscripts. They let everyone read them and destroy them and remake them and carry them into the future. We haven’t reached that radical openness yet. It’s time for us to imagine a new world.

When I taught Cavendish this year, I used this e-version — my students were a bit happier with this than with EEBO: https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/c/cavendish/margaret/blazing_world/index.html

There’s also this text version: http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/newcastle/blazing/blazing.html .

I’m grateful to learn of the new, proper facsimile though! Love your posts.