When you’re encountering early modern texts for the first time, you might be surprised not only that they use such variable spelling (heart? hart? harte?) but they seem to use the wrong letters in some places. And then there are funny abbreviations! Even adept readers of early texts might stumble when it comes to making sense of some of this, especially when faced with producing transcriptions. To try to make things a bit simpler, here’s a primer on reading early modern letterforms and an account of The Collation’s house transcription style.

u/v, i/j, s/long-s

One of the first oddities that catches my students’ eyes is what seems to be mixed-up uses of “u” and “v,” and “i” and “j”: “vsual” or “iustice,” for instance. It’s not hard to work out what those words are, I don’t think (“usual” and “justice”), but it’s easier when you learn that these follow established rules, rather than randomly substituting one letter for another. In both cases, it’s helpful to think of the two forms as different shapes of the same letter, the usage of which is determined by its location in the word. For u/v, “u” is used in the middle and end of words, while “v” is used at the start of a word; for i/j, “i” is used at the start and in the middle of words, while “j” is used at the end. This is akin to written languages today that use a different letter form when that letter occurs at the end of a word—as in Hebrew, for instance, with a nun (נ ) and a final nun (ן)—although it’s not a typographical feature that has survived in English. The shape of the letters has nothing to do with their pronunciation; think, perhaps, of the different ways we voice the letter “c.” (These rules apply to the lower-case form of these letters; uppercase usage tends to use V and never U up until the middle of the seventeenth century [see Goran’s recent post for examples of that shift in Flemish books].)

What tends to trip readers up more frequently is the use of the long-s, which to our eyes looks so akin to an “f” that it can sometimes be very hard not to read it that way.

But the rules for long-s are, as with u/v and i/j, follow the letter’s placement in the word: short-s at the end of a word, long-s at the beginning and in the middle. (Transcriptions that rely on OCR to recognize characters mix these letters up to sometimes hilarious, and confusing, results.)

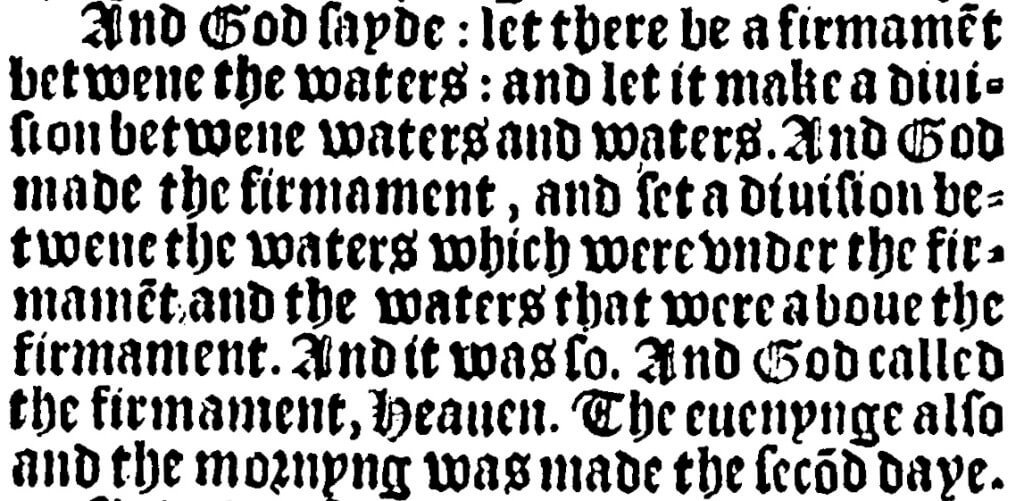

The examples I’ve given here are all in roman font, but they hold true in other fonts and in handwriting, as well. But black-letter fonts introduce additional letterforms, as does handwriting. There are multiple forms of the letter “r” in black letter; secretary hands have multiple forms of “r” as well as of “e.”

abbreviations

The first abbreviation that can throw readers into confusion also stems from a letterform confusions: ye. Given that that first letter looks exactly like a “y” it’s not surprising that it’s survived as a kind of joke indication of oldness.

But what we are reading today as a “y” would have been read as the now obsolete letter thorn: “ye” is an abbreviation of “the.” (Of course, “ye” is a word in its own right—an equivalent of “you”—but the superscript “e” indicates an abbreviation for “the.”) Similarly, “yt” would not be “it” but “that.”

The use of a superscript to indicate an abbreviation is a frequent one: “wch,” “Maty,” “yor.” Other abbreviations can be marked with a macron or tittle to indicate a missing letter, typically an “m” or an “n”:

There are many other abbreviations in use in manuscripts and in early printed works, but these are the ones that crop up the most frequently.

transcriptions

Being able to read early modern texts easily is one thing; making decisions about how to transcribe those texts is another. Different projects will require different standards. Do you want a fully modernized edition, one that adapts the text’s spelling and punctuation to conform with modern usage? Do you want a diplomatic transcription that strives to preserve and indicate all the original textual and often material features of the document? The former will produce a very readable text, albeit one that loses most of its historical situatedness; the latter will produce a text rooted in its time, but often at the expense of readability.

On The Collation, we strive for a semi-diplomatic style of transcription that will work for printed texts, manuscripts, and graphic materials. Our goal is to present texts that are readable but that are also faithful to our belief that these texts are historically embedded in material texts: we look at objects through a historical lens, and we want our transcriptions to convey that.

In practice, this means we follow these guidelines:

- We stick with the original spelling, punctuation, and capitalization.

- We maintain the u/v and i/j distinctions of early texts; we don’t do the same for the long-s largely because there is no adequate equivalent of that letter in modern fonts. ((Yes, there is a Unicode symbol that resembles the long-s, and some computer fonts also offer options akin to the long-s, but these are not standard and often do not render properly on all computers. Not to mention the fact that over-zealous transcribers sometimes end up using mathematical symbols instead!))

- We do not usually adhere to the text’s original font choices (that is, when a text switches from roman to italic for a proper name, we stay in roman throughout).

- Since there is no modern thorn letter, we change “ye” to “the” with the “th” in italics to indicate it has been altered: “the.”

- We expand abbreviations, using italics to indicate the letters omitted in the original. Letters that were superscript are lowered without being italicized.

- Brevigraphs like “&” or “&c” are preserved as is.

So, to put into practice a lovely example of biblical text:

“And God sayde: let there be a firmament betwene the waters: and let it make a diuision betwene waters and waters. And God made the firmament, and set a diuision betwene the waters which were vnder the firmament and the waters that were aboue the firmament. And it was so. And God called the firmament, Heauen. The euenynge also and the mornyng was made the second daye.”

Every project will have its own transcription needs, and what works for The Collation might not work for you. But now, at least, we’ve shared what we do and our reasoning behind it!

Update February 12: My thanks to Goran, whose eagle eye caught my mistranscription of “Heauen” as “Heaven” (now corrected). It just goes to show the most important thing about transcribing texts: as much as you focus on remaining faithful to original orthography and spelling, it’s awfully hard not to automatically “correct” such things!