Last week’s crocodile mystery may have been a bit too mysterious, but I hope that today’s post will inspire you to look for similar mysteries on your own. Here’s a close-up detail of what I was asking about:

As with nearly all photographs shared on this blog, if you click the image, a larger version will open in a new window. What might have looked like a smudge if you hadn’t enlarged the image, is now clearly a smudge worth paying attention to! More specifically, it’s a smudge made up of individual lines and whorls, a smudge made by an inky printer’s fingers.

One of the reasons that I didn’t share only this detail in last week’s post is that I wanted the whole context for the fingerprint to be visible. The assistants in a print shop have long been known as printer’s devils, a name assumed to stem from their dark, ink-covered appearance. In his 1683 Mechanick Exercises: Or, the Doctrine of Handy-Works. Applied to the Art of Printing, Joseph Moxon provides the following definition for “devil”:

The Press-man sometimes has a Week-Boy to Take Sheets, as they are printed off the Tympan: These Boys do in a Printing-House, commonly black and Dawb themselves; whence the Workmen do Jocosely call them Devils; and sometimes Spirits, and sometimes Flies. ((Moxon, vol 2, page 373))

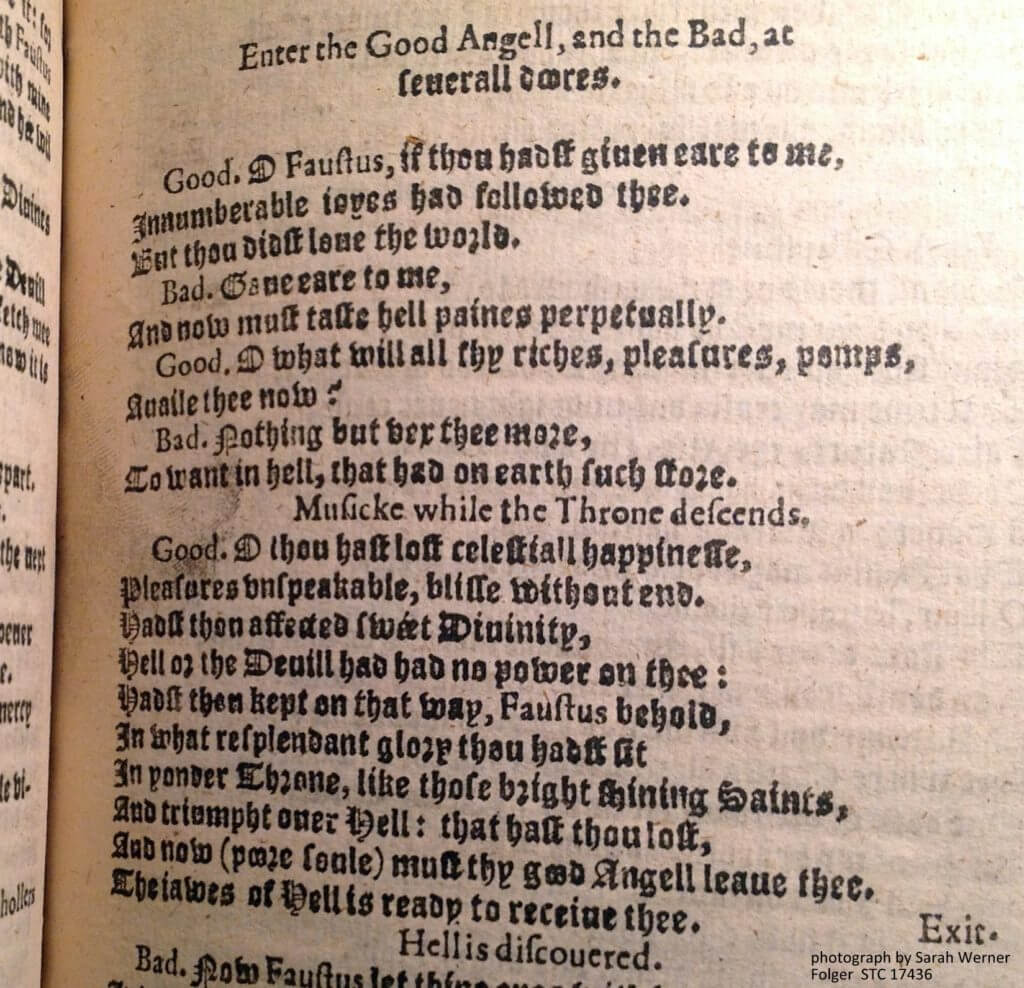

And the lovely coincidence here is that the text itself is concerned with the appearance and influence of devils. It’s from a 1631 printing of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, near the end of the play in a moment of dialogue between the Good Angel and the Bad Angel. ((The text of Faustus exists in two different versions: the A-text, which is shorter, and the B-text, which contains additions from other writers. This printing of the play is of the B-text, and this scene is one of those additions.))

In other words, that the mark appears on this particular play in this particular section lets us joke that not only do devils exist—they leave fingerprints!

Usually when we talk about a book’s fingerprint, we refer to a series of words or characters that identify the edition or setting of a book. (This post provides more details about the various methods of such bibliographical fingerprints.) But fingerprints can also be a literal part of a book’s history, a wonderful trace of the bodies that make books.

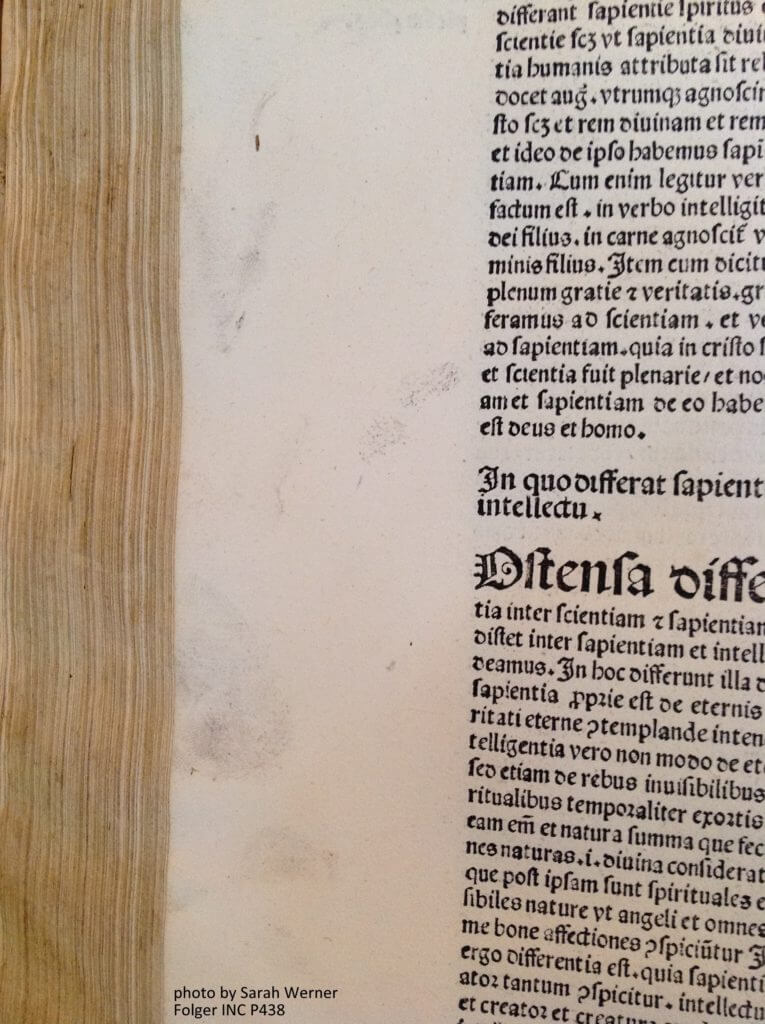

One last note: The reason that I’m assuming that this is a fingerprint left by someone in the print shop, as opposed to a later user of the book, is the location of the print. Given that it disappears into the gutter, I’m assuming that it was left when this leaf was still in sheet form: take the paper off the tympan, hang it up to dry, and it seems entirely possible that the mark will end up in the middle of the sheet. Someone reading this book, however, would be more likely to leave their smudgy mark on the margins. These prints, for example, could have been made in the print shop or in a reader’s hands. (Click on the image to open it in a new window, and click it again to enlarge further and to see the lines and whorls.)

Marks left by a reader are not unexciting, but the thrill of a printer’s fingerprints is greater, I think. If you’ve come across such prints in books you’ve worked with, let us know in the comments. And if you have photos of Folger items with such prints, don’t forget that you can add them to our Flickr group, “Folger Collection, by Folger Readers.”