I’ve spent a good portion of my summer thinking about how to revise my syllabus for the early modern book history seminar I teach. This fall will be the sixth time I’ve taught this course, and while it’s been working well, it’s also time to shake it up a bit. Too much familiarity with the material doesn’t breed contempt, but it can lead to a complacency. I’ve been browsing in the stacks, reading new finds, and thinking about what I want students to learn and how best to achieve that.

There are some key factors that shape how I approach teaching this course. First, it’s a multi-disciplinary course, drawing students from different majors, primarily English and History, but also French, Art History, Theology, and Music. Because it’s important that all these students feel welcome in and learn from this course, it cannot be too oriented toward any single subject. On the other hand, it is a course at the Folger Shakespeare Library and one that draws on the strengths of the Library’s collections; that means that the focus of the course is explicitly early modern, concentrating on the last fifteenth century through the end of the seventeenth. The last major consideration in shaping this course is that its purpose is to provide students an opportunity to do hands-on research with rare materials.

Rather than moving through the period chronologically, or through some haphazard thematic pile-up, I decided from the course’s first incarnation to foreground the methodological differences in thinking about books and their histories. The syllabus is organized in three units: the first considers books as physical objects, the second studies the relationships between books and culture, and the third explores books as vehicle for texts. (Actually, because it appeals to my corny sense of humor, the syllabus isn’t divided into units but volumes, along with a preface and an introduction; there are actually also some interludes, but I really need to find a book-centric metaphor for those.) In many ways, these approaches sync up with disciplinary interests: analytical bibliography, history, and textual studies. Leslie Howsam’s great book on Old Books and New Histories: An Orientation to Studies in Book and Print Culture is tremendously useful in thinking through the disciplinary orientations of the field which is, after all, a big mash-up of approaches and histories. To a large degree these separate frameworks are fictional: you can’t think about books and culture without knowing something about the process of making a book, nor the other way around. But dividing the syllabus this way keeps the issue of how we think about books front and center, an especially useful tactic when we are also trying to think about how we are not thinking about books.

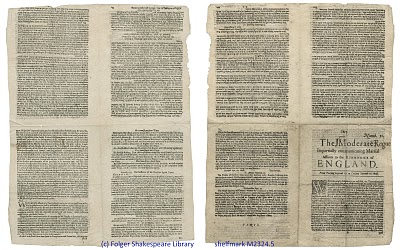

That tactic is only useful if students are aware of it, so we begin the course with a session that explicitly asks, “What is the history of books?” It features Robert Darnton’s classic essay, of course, along with some D.F. McKenzie and Roger Chartier, with the three selections bearing the burden of tracing the different ways in which we might approach the field. The next session on incunabula gives students a way to start thinking about the approaches in larger terms before we get down to the nitty gritty of how books were made. We only spend a couple of weeks on this, focusing mostly on the big points: different formats and impositions, the practice of casting off and setting type, recognizing chain lines and watermarks, and differentiating between woodcuts and engravings. (Those of you in the field will recognize the quarto imposition in the image at the top of this post.) I’m not always sure how much time to devote to this. Some semesters it feels like we’re spending too long (or at least, too long reading Gaskell, which is a bit of a slog and is often overkill, but is still the best thing for what I want them to learn). Other semesters it feels like we’re racing through this section too fast. But if we spend longer on the physical book, that cuts into the time we have to think about books in other ways; if we spend less time, they don’t know enough about the process of making books in order to ask important questions later on.

The second volume of the class moves from the physical making of books to the book trade and intersectionsbetween books, printing, culture, and economics. I structure it roughly around the roles of makers and users: we look at the role of printers and the Stationers Company, think about the creation and deployment of authors, and the use of books by readers and libraries. This has been the trickiest part of the syllabus to set–so many possibilities, so little time! This year I’m really looking forward to using Andrew Pettegree’s new book, The Book in the Renaissance, which talks about books in exactly the right sort of blended approach and complexity for my purposes. I’m really loving this book, and it’s been getting some great reviews: it’s both smart and accessible and even if you’re not a student in a book history course, it’s well worth reading. Also, look at that beautiful cover! Other key readings come from Zachary Lesser’s Renaissance Drama and the Politics of Publication, Bill Sherman’s Used Books, and Ann Blair (I’m really looking forward to the arrival this fall of her new book, Too Much to Know, which, like Pettegree’s book, is coming out from Yale and, also like his, is priced at a reasonable $45 for a hardcover). There’s also some more Chartier and Darnton, mixed in with a small dose of Foucault and de Certeau, of course. The real payoff of this section, however, comes in the interplay of the readings with the students’ research projects: the readings model different ways of thinking about the questions being raised, but the work is in making those questions and approaches useful when working with the book in hand.

The course wraps up with a couple of weeks thinking about how the material forms of books affect the transmission and reception of textual meaning. We go back to questions of printing, but this is really the textual scholarship showdown: what does an editor do? I like Robert Hume’s piece on “The Aims and Uses of ‘Textual Studies'” (PBSA June 2005) to start students thinking about what makes a ‘good’ edition, and I’m very fond of Random Clod’s “Information upon Information” (TEXT 1991), which is smart and funny and outrageous. We combine those readings with a lot of looking at different examples of editing, from the more typical to the more crazy (the Middleton Collected Works is chock full of different and provocative editorial practices–and there’s now a paperback edition for only $40!).

After having spent the summer thinking about how to shake up the syllabus, I’ve come right back to where I started: the structure of the course is still the best way to go about doing what I want to do. I’ve tweaked some of the readings, and I’m looking for a different set of rare materials to bring into the classroom to help us put the readings into action. But I’m actually pretty happy with how we’re going about things.

There is one place that I would like to make changes, and that’s in the interludes or case studies. In the second half of the course, we have a couple of sessions devoted to single topics that let us bring together all three legs of our book study triangle. In the past, we’ve had one class devoted to Bibles and one class devoted to Shakespeare. Both work really well for thinking about how the materiality of books shape the reception and use of texts and interact with the cultural forces at play and being generated. Plus, both give me a chance to bring some lovely books into the classroom. (And, given my training as a Shakespearean and as a performance scholar, it’s fun to have a class to talk about those books and about the interplay between performance and print.) The downside, as I see it, is that both draw on ideas of The Book in ways that don’t displace what is already a tendency in the class and in the field: to think in terms of books rather than other printed objects. I try to talk about this in class frequently: books are just one of the things that made up the printed output in the early modern period. Broadsheets, indulgences, and almanacks, for instance, are just some of the things that were as important as books–as Peter Stallybrass and others have pointed out, it’s the printing of these ephemera that sustained early printers, not the big books that we now value. I could do a class on newssheets, and am considering that, although given my comparative unfamiliarity with that world, it does make me a bit nervous. I’m also considering focusing on some more utilitarian books instead, like school books, perhaps.

There are two other qualifications for this syllabus, which I recognize, but they remain. The first is that this really is a print-centered course. It doesn’t reflect my own sense of the ways in which manuscript and print coexisted in the period and influenced each other. Part of my reluctance to bring manuscripts in has to do with teaching students paleography; as it is, I spend an hour or so doing a quick-and-dirty introduction to basic secretary hand and mixed italic. (Okay, it’s not dirty; we read a letter from Henry Cavendish to his mother, Bess of Hardwick.) I also don’t want to open up the focus of the class too far, or to start worrying about handling manuscripts. I do try to bring in ideas of manuscript culture in other ways, but it isn’t a regular feature of the course.

There are two other qualifications for this syllabus, which I recognize, but they remain. The first is that this really is a print-centered course. It doesn’t reflect my own sense of the ways in which manuscript and print coexisted in the period and influenced each other. Part of my reluctance to bring manuscripts in has to do with teaching students paleography; as it is, I spend an hour or so doing a quick-and-dirty introduction to basic secretary hand and mixed italic. (Okay, it’s not dirty; we read a letter from Henry Cavendish to his mother, Bess of Hardwick.) I also don’t want to open up the focus of the class too far, or to start worrying about handling manuscripts. I do try to bring in ideas of manuscript culture in other ways, but it isn’t a regular feature of the course.

The other qualification is how England-centric the class is. One of the reasons I’m pleased about having Pettegree’s book to work with is that it really encompasses a much wider range of print practices. But the fact is, most of my students are working on English literature or history, and so many of the resources that we have available to us (the STC and the Stationers’ Register, just to name the two biggest ones) are focused on England, thanks to scholars’ long-standing fascination with Shakespeare. I’m not super happy with an England-, or even more accurately, a London-myopia but that’s going to take me a while longer to change.

I’m going to continue tinkering with my syllabus, but since class starts at the end of next week, it will soon have to be done, and then you’ll find it online at the Folger Undergraduate Program‘s homepage. I haven’t talked about what sort of assignments students do, or the kinds of research they’ve done in the past, but there are some posts describing some of those projects, and you’ll find the assignments detailed on the syllabus once it’s up.

In the meantime, a quick word about the image at the top of this post: It’s the front and back of an issue of a 1648 newspaper, The Moderate. If you download the images (follow this link) and print them on the front and back of a regular-sized sheet of paper, you’ll have your very own small-scale newspaper and folding exercise. Have fun!

>I love this musing on teaching and thinking about books. One way in which I'm shaking up the graduate historical methods class I'll teach this fall is to incorporate some materials from the history of the book as well as histories of reading. I'm finding this is a great way to get students thinking about their sources from a new perspective and much of the strategies remain applicable across not just multiple disciplines but for different regions and eras.So thanks for your discussion as it's giving me a few more angles to consider as I finish my own syllabus!

>Great post. Which McKenzie essay(s) are your required reads? It was reading McKenzie's 'Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts' 3 years ago which instantly transformed me into being obsessed with book history.Also do you know the provenance of the Folger copy of that issue of the Moderate – in particular who has graffitied it?

>hey Nick–I thought you might like that image–it's such great reader-response! I don't know much about its provenance. The catalogue record is here but notes only that we have only that single issue. I'll check more when I'm back at work next week. But I love that the annotator needed to deface it so carefully and then also, apparently, keep it!As for the McKenzie, I have them read "The book as an expressive form" that first session and encourage them to read the rest of Bib and Sociology of Texts on their own. It's so great!