A friend shared a recent article with me from Der Spiegel that touches directly on the subject of books and owners and their emotional and historical connections. The piece, “Retracing the Nazi Book Theft,” examines the legacy of the Holocaust for German libraries: thousands of books that were stolen from Jewish owners and that remain in the collections of German libraries.

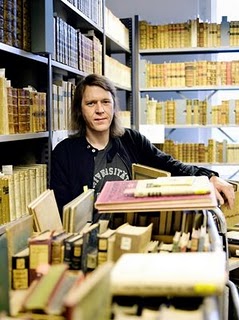

This photo (from the article) is of Detlaf Bockenkamm, a curator at Berlin’s Central and State Library who been tracing the former owners of books stolen by the Nazis. Here he is standing with some of those books, part of the Accession J section, consisting of more than 1000 books acquired by the Nazis “from the private libraries of evacuated Jews” and then integrated into the Library’s collection.

Just as paintings were systematically taken and claimed by the Nazis, so too were books and other cultural and valuable items. The stolen books have gotten significantly less attention in the media, however, perhaps because they are less spectacularly valuable than some of the paintings, perhaps because we are less used to thinking of books as important objects. But the repatriation of such paintings and books is less about their material worth and more about their emotional and memorial resonances:

Nevertheless, Germany’s Federal Commissioner for Culture Bernd Neumann believes that museum employees and librarians have an obligation “to devote particular attention to the search for those cultural goods that were stolen or extorted from the victims of Nazi barbarism.” Neumann points out that, more than just “material value,” what is at issue here is “the invaluable emotional importance that these objects have when it comes to remembering the fates of individuals and families.”

You can read the article for more information on how the search is going. It’s painstaking, as you might imagine. Even aside from the reluctance of many libraries to focus on the task, there is the difficulty in going through the sheer volume of accession records, of looking through individual books for traces of their former owners, and then searching for those owners or their relatives today.

Given my recent posts on the social transactions of books, the timing of the Spiegel article reminds me that books bear witness to history in ways that are much larger than just a daughter’s inheritance from her father, or a mother’s gift to her son. And it opens up questions, too, of libraries and their obligations to books and owners. I’ve been doing a lot of thinking recently about libraries–what libraries do, about the tension for rare book collections between preserving the past and making it accessible. I’ll post more about that in the future.