My last post lamented pristine books that remained uncirculated and lonely on their shelves. This post is a teaser for future posts examining how very much we can learn about the ways that books circulate in readers’ lives.

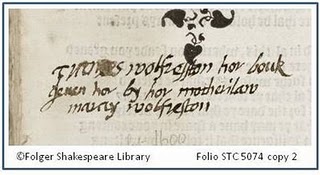

Above is a detail from a 1550 edition of Chaucer’s collected works. On a leaf in the middle of the volume is carefully inscribed “Frances Wolfresston hor bouk geven her by her motherilaw Mary Wolfreston”.

That in and of itself is a rich testament to the circulation of books. But there is more to be discovered. If you examine the Folger’s catalogue entry for this volume, you will notice that one of the associated names is “Wolfreston, Frances, 1607-1677, inscriber”. If you follow that link, you will discover that the Folger has an additional 10 books signed by Frances Wolfreston in its collections. Frances Wolfreston, you will soon realize, was an early modern book collector and her library of books, nearly all carefully inscribed with “Frances Wolfreston her bouk”, can be found dispersed among some of the greatest library collections today. Another post will be devoted to exploring her and her collection.

One more tidbit teaser: you will also notice when looking at the catalogue entry that there are lots of other inscriptions recorded as being in this book. There are a number of other Wolfreston family members, suggesting that this volume was passed on down through the family; there are also a collection of other signatures from a different family suggesting that it was similarly passed down through their family. More about that, too, in the future.

In the meantime, two quick quirks that I like:

In her inscription, Frances spells her last name differently than how she spells her mother-in-law’s. Her son Francis settled on yet a different spelling, choosing primarily to record his name as Wolferstan. We all know that early modern spelling was full of variants. But so, too, were early modern names. It seems very strange by our standards today: ask any other Sarah whether her name is spelled with an “h” or without the “h” and you’ll discover that we are all very insistent on the importance of that difference.

Quirk two: when you follow the link for Frances Wolfreston to find other books that she owned in the Folger collection, what you actually find is that the Library appears to differentiate between those in which she is an “inscriber” and those in which she “signed”. No difference in the books themselves. It’s just a nice reminder of the many ways in which books are handled by many different people, and those human differences and foibles leave their traces everywhere.