Today is Ada Lovelace Day. Ada Lovelace is often referred to as the first computer programmer, based on her 1842 treatise on Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine; Ada Lovelace Day began in 2009 as a way of increasing the profile of women in Science, Engineering, Technology, and Math (commonly referred to as STEM fields).

I’m not in a STEM field (though I’m the almuna of a college that prides itself on turning out huge numbers of women who are). But you know who we could see as being early STEM pioneers? Printers. Early modern printers were using a new technology that had a radical impact on their world. ((Please don’t send me comments about how the printing press didn’t cause any revolutions. No one thing changes the world in isolation. But moveable type was fucking huge.)) And you know who we find in printing in early modern London? Women.

Here’s a fun thing to try: search the ESTC‘s publisher field for “widow.” There’s 352 results! Now trying searching for “Elizabeth”: 405 results! Jane? 112!

Here’s a fun thing to try: search the ESTC‘s publisher field for “widow.” There’s 352 results! Now trying searching for “Elizabeth”: 405 results! Jane? 112!

I do an exercise with my students on using the Stationers’ Register and during the course of tracing one book’s passage through the Register, we come across three different women who printed or published the book. It’s sort of an accident that that’s the book we work with it, but it’s a really effective exercise. My students are always shocked that there are women working as printers in this period. But why is it so shocking?

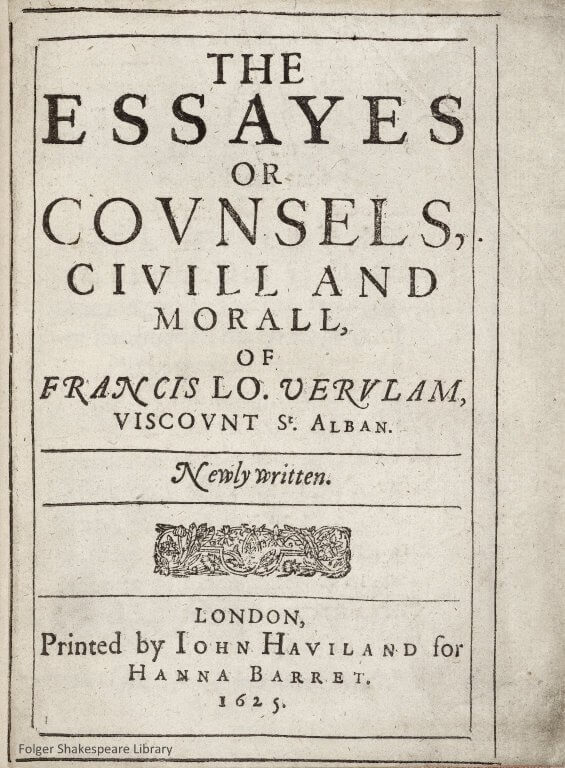

I suspect that it is, in part, because we have become so used to thinking about the early modern period as being repressive for women. Chaste, silent, and obedient. But that’s an assumption that blinds us to the lives of actual women in early modern England. Women might have been supposed to pass from father’s household to husband’s without ever being subjects in their own right. But if you look at the records, you find women owning property and conducting business. Not just one or two, but handfuls of women. I’m not going to claim that the opposite of “chaste, silent, obedient” is true—women were not by any means empowered or enfranchised—but our blind spots shouldn’t mean that we don’t reconsider our assumptions when we start to see what we’ve been missing. How many of the unnamed printers in imprints are women?

I suspect that it is, in part, because we have become so used to thinking about the early modern period as being repressive for women. Chaste, silent, and obedient. But that’s an assumption that blinds us to the lives of actual women in early modern England. Women might have been supposed to pass from father’s household to husband’s without ever being subjects in their own right. But if you look at the records, you find women owning property and conducting business. Not just one or two, but handfuls of women. I’m not going to claim that the opposite of “chaste, silent, obedient” is true—women were not by any means empowered or enfranchised—but our blind spots shouldn’t mean that we don’t reconsider our assumptions when we start to see what we’ve been missing. How many of the unnamed printers in imprints are women?

I don’t know very much about the history of women printers in this period, or about female labor, but there’s a book coming out next year that should help me get a better sense of the range of activities: Helen Smith’s “Grossly Material Things”: Women and Book Production in Early Modern England. If you can’t wait that long, you can check out her article in TEXT on the subject. ((“‘Print[ing] your royal father off’: early modern female stationers and the gendering of the British book trades”, TEXT: An Interdisciplinary Annual of Textual Studies, 15 (2003), 163-86.)) And there are a couple of sites out there to start filling in some gaps: a blog post about the early American printer Dinah Nuthead and an exhibition from the University of Illinois library. The more traces of this history I find, the more I want to learn!

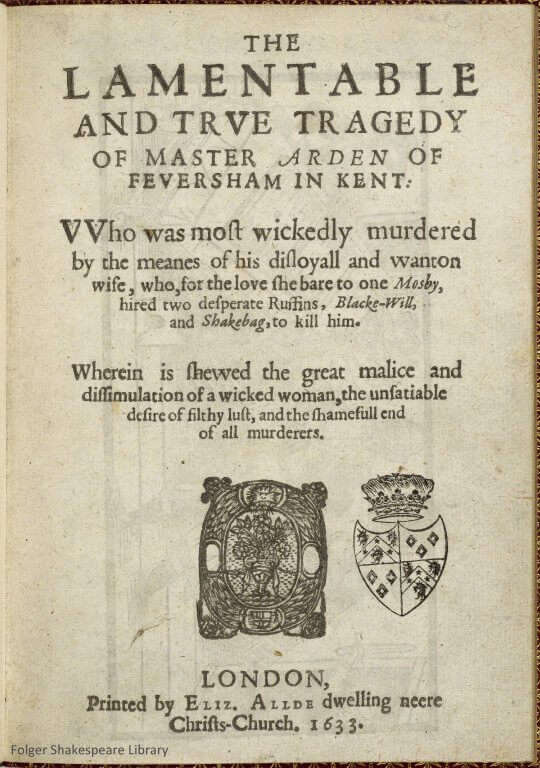

And it matters that we learn these things. It matters that we understand the past as a variegated and nuanced time in part because it enables us to see our own time that way. It matters that we remember Ada Lovelace and Rosalind Crick Franklin and Elizabeth Allde because it matters that they contributed to our knowledge of the world and that we can contribute too.

UPDATE: What a horrible thing to mistype Rosalind Franklin’s name in a post about women pioneers in STEM fields and to give her Francis Crick’s last name instead! I’ve fixed it now. Go read about her and then go read Kate Beaton’s comic in Hark, a vagrant.

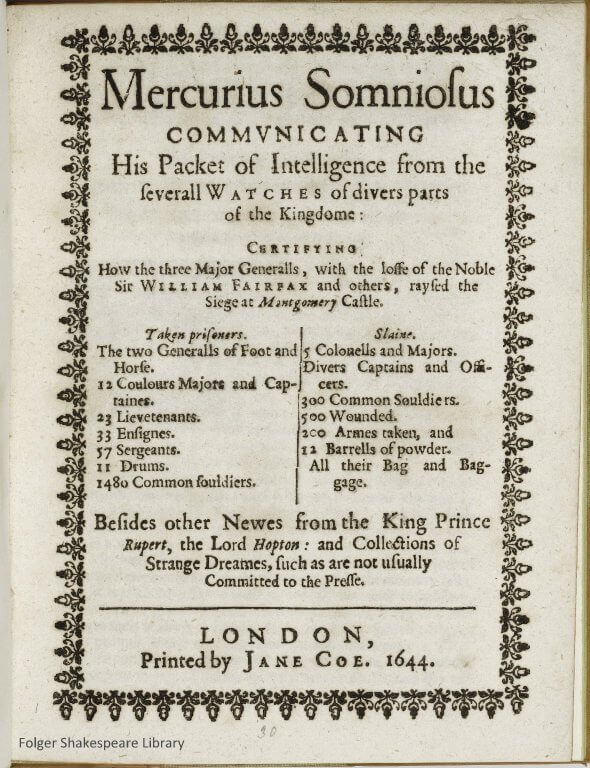

I really enjoyed this post – thank you for putting it together. It is very true that the nature of our sources (patchy, and mostly produced by men) can massively obscure the role women played in all sorts of trades and professions, particularly printing. You have reminded me to put up some material about a female printer I’ve been looking at, Jane Coe: more here. http://mercuriuspoliticus.wordpress.com/2011/10/08/for-ada-lovelace-day-jane-coe/

I’m so thrilled this inspired you to share some of your Jane Coe research. Share more! One of my favorite things in talking about this with students is the way it makes us reexamine not only our own assumptions but to be aware of the gaps (deliberate or not) in the sources we use. That Plomer bio from your post (go read it, people!) is so telling. Thank you for that.

An excellent exhibit catalogue on women printers: “Letra y duelo: imprentas de viudas en Málaga siglos XVII-XIX”, selección y textos de José Calvo González (Málaga: Ayuntamiento de Málaga, Área de Igualdad de Oportunidades de la Mujer, 2009).

thanks! I’ve just been in conversation with someone on twitter, Esther Villegas de la Torre, whose doctoral dissertation on 17th century Luso-Hispanic women printers will be published as a book next year. I know nothing, alas, about that area so am looking forward to exploring more! UPDATE: I’ve slightly misspoken: she’s currently researching printers; her dissertation focused on women authors. I’ll have to wait a bit longer to learn about women printing in Spain!

Thanks for this: I hadn’t come across women printers in early modern England. You might be interested in Susan Jackson’s work on women printers of music, e.g. Catherine Gerlach who was active in the 16th century.

Thanks for the reference–I’ll definitely check her work out!

Thanks for this post. As you note, there were also women printers in early America (following in Dinah Nuthead’s footsteps, even if they didn’t know who she was). From my own work on the Revolutionary period, I know that more than half a dozen women — mostly widows — operated printing offices long enough to maintain or earn colony or state printing contracts, and one (Mary Katherine Goddard, the sister of printer William Goddard) served fifteen years as Baltimore’s postmaster. I’m glad to hear there’s some literature on women printers in England, and hopefully it’ll help link up what’s going on in the colonies.

Thank you for a great post. I really was unaware of women printers in the early modern period. Also, thanks for introducing me to Rosalind Franklin.

Yay, Ada! wish I’d known she had a “day”, would have refreshed this. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/gerit-quealy/allen-west-lady_b_905011.html

Thanks for the add’l info, great find this site.

What a great post – and thanks for mentioning the book! If you want a sneak preview I’d be happy to share the relevant chapters. I’m sure you already know them, but there’s also Susan Broomhall’s book on women in the early modern French book trades, and several helpful articles by Maureen Bell. And for later in the period, of course, there’s Paula McDowell’s great Women of Grub Street. I do a similar exercise with my students – searching for early modern women in the Stat Co Registers and other sources, and they’ve done some great detective work!

I would love a sneak preview! I’m hoping to devote more time to this in next semester’s course, so that would be very useful. I’ll email—

Thank you, everyone, for sharing information about additional resources! I’m thrilled that it’s been a useful post in introducing the subject and for gathering more directions for research. I’m not sure why I forgot to mention Maureen Bell’s work in my post, but I should have (I’ve only recently gotten my hands on the piece on women in the English book trade and am very much looking forward to reading it!). So, for those of you who like to have your Googling done for you:

Maureen Bell, “Women Writing, Women Written” in A History of the Book in Britain vol.IV, ed. J. Barnard and D.F. McKenzie with the assistance of M. Bell (CUP, 2002). (Chapter 20, pp.431-451)

Maureen Bell, “Women in the English Book Trades 1557-1700”, Leipziger Jahrbuch zur Buchgeschichte, 6 (1996), 13-45.

Susan Broomhall, Women and the Book Trade in Sixteenth-Century France, Ashgate, 2002.

What an excellent resource to stumble upon (after simply googling ‘women printers’). I’m so excited for Helen Smith’s book!!! I’m doing research for a novel about “printing widow” Sarah Eaves, who was married to John Baskerville. I wonder if Helen Smith’s book contains much on the late period? I’m interested in the second half of the 18th century. Thanks for all the great resources. S.