No, I don’t mean it’s time to write your own news sheet newsbook. It’s time to fold your ownnewsbook! Why would you want to do this? Well, for one thing, it’s a handy way to understand and demonstrate to others the general principle of early modern format: multiple pages are printed onto a single sheet in the correct order so that when folded, they appear sequentially. It’s like magic! Or, um, folding.

Above is a numbered example of the same newsbook that I used as an image in my last post. The red numbers are page numbers: folded in the right way, you’d get an 8-page booklet in the order indicated. But if you look closely, you’ll see that the actual news sheet doesn’t have page numbers. Instead, there are signatures: at the bottom of the first page is a tiny, blotted “L”; at the bottom of the 5th page is a tiny “L3” (the “L2” has been cut off at some point when the page was trimmed). These are signature marks that count off by leaves. What’s a leaf, you ask? It’s a physical unit of paper: when you turn the page in a book, you are actually turning a leaf of paper. Early modern printers would have thought in terms of sheets and leaves, not pages, when they were figuring out how to print a work. Depending on the imposition (how the text is laid out on the sheet), you could end up with different numbers of leaves: 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24. A quarto imposition results in a sheet of paper being turned into 4 leaves; there are 2 pages to each leaf (a recto side and a verso side), so there are 8 pages in all. The blue letters and numbers show the signatures. One thing that throws off beginners is understanding how recto and verso relate to each other. They do not mean right and left but front and back. When this pamphlet is open so that the 5th page is on the right-hand side of the opening, and the 4th page is on the left-hand side, the 5th page is the recto side of the third leaf in this gathering (L5r, for short), and the 4th page is the verso side of the second leaf in this gathering (L4v). Gatherings are numbered (well, lettered) in order so that the printed sheets of paper can be assembled in the right order in the final book. This is the “L” gathering, and it would be preceded by the “K” gathering and followed by the “M.” Once you start thinking in terms of leaves and gatherings, which are the units that are most helpful for printers, rather than pages, which are primarily useful for readers, it’s pretty easy to keep it all straight.

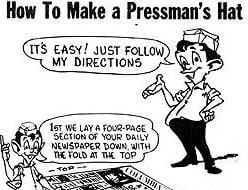

You can follow this link and print off the two images as a single sheet of paper (or print separately, of course, and then run them through a copier to make it two-sided) and practice folding it as a quarto yourself. When you’re done, you can try folding it into a tiny little pressman’s cap, following the instructions that appear in this lovely piece, “The Newspaper Man is Defunct,” from The Cape Cod today.

By the way, my syllabus is now done(ish) and can be found online in pdf form.

Correction: The spelling of recto has been changed to reflect its actual spelling. Oops.

Correction 2: I have corrected my usage of “news sheet” to reflect the more accurate term “newsbook” throughout the post. See the comments below for an explanation of the difference between the two!

>why "rechto"? never seen it spelled like that, so curious to know!

>Oops–no reason for that spelling other than just not paying attention! The correct spelling is, as you note, 'recto' and once I'm back at my computer I'll have to correct it. That's what happens when I post after teaching for 3 hours…

>These are very helpful posts: thanks! I appreciated being able to look at the carefully conceived syllabus, and I love the printable pdf of a news sheet with folds numbered. These posts signal how blogs can really enhance teaching. I hope to hear more about how the course's 3-part structure works. It looks very promising. Again, thanks!

>I loved this post – and indeed my tutor for my MA made us do a similar exercise, cutting out and folding our own pamphlets in class, which was brilliant fun as well as teaching about recto and verso much more easily than just trying to explain it verbally. But the pedant in me has to point out (in the nicest possible way!) that the Moderate is a newsbook, not a news sheet. That's what contemporaries would have called it, anyway, because it's a quarto pamphlet rather than a half-sheet folio format.

>Nick, I really appreciate the gentle correction! I knew when I posted this after hours of teaching that I was risking making mistakes in it . . . And this just proves my point in my last post about not feeling knowledgeable enough about newsbooks to teach a session devoted to the subject!On the subject of cutting-and-folding, though, I totally love what your tutor did! In the past I've made my own for students to fold (and I've a great one from a 1564 octavo which is misfoliated in interesting ways), but I think I might try what you did this time: have the students make their own. So thank you, on both accounts!And Anna, thanks for your nice comments. The rest of you can glimpse more of Anna's reactions over at her post at Early Modern Online Bibliography.