I’m in the midst of my working vacation, and have been slogging through–I mean, thoroughly enjoying–lots of As You Like It promptbooks. It’s not not fun, it’s just that there are so many productions, and at the moment I’m only looking at the Royal Shakespeare Company ones! Starting with Vanessa Redgrave as Rosalind in 1961 through Katy Stephens in the production I saw the other night, there are thirteen different RSC productions. It’s being staged every 4 years! And that doesn’t even count the transfers to London or Newcastle.

Aside from being struck by the huge popularity of this play (at least, a popularity with the audience; the reviewers tend to range from blase to a despairing animosity toward the play), I’ve been struck by the staggering number of books that these productions generate. And I don’t mean books like the sort I’m writing, books that are about the productions or about the play. I mean books that come into being through the process of putting together a production. There’s the published text that is the basis of the production, the rehearsal promptbook(s) in which the blocking and cuts are worked out, the production promptbook recording the final versions of those blocks and cuts, the stage manager’s script with cues for entrances, lighting, and sound. There are of course the individual actors’ scripts (which don’t tend to be kept in production archives), notebooks that the director or other theatre artists keep during the rehearsal process, the musical score, the stage manager’s reports, the costume bible.

After my last post on printed drama, in which I insisted that plays aren’t books, a friend wondered whether I wasn’t being overly simplistic–can’t plays sometimes be books as well as performances? I’m still reluctant to think of printed books as plays rather than as, say, drama, or playbooks, or some other category that is subtly different. But I am struck doing this research how many books come into being during the process of creating a performance.

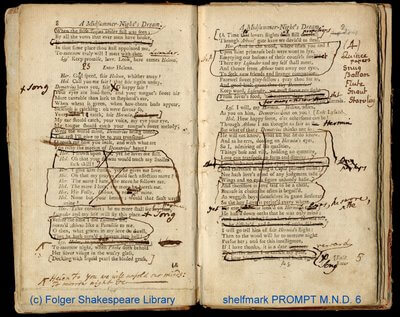

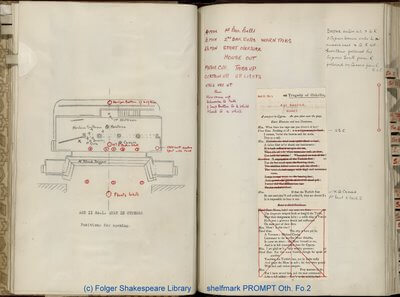

The picture at the top of this post is from the very tidy promptbook of the 1930 Othello starring Paul Robeson at the Savoy Theatre in London. You can see that it’s a workbook made with the cuttings of a printed text, reassembled with diagrams and cues and other performance details. The picture below is from an earlier promptbook, David Garrick’s working out of his 1773 Drury Lane production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. There’s lots of cutting and rearranging going on. A better example of Garrick’s working method can be found online as part of the Folger’s past exhibition about Garrick, in the section “What is a promptbook.” There you can see his working book for his 1773 Hamlet, full of tipped-in sheets, and folded down pages. It’s really remarkable, and a great example of how books are adapted by their readers for their own purposes as well as of how playbooks are remade into performances.