Last weekend I attended a wonderful conference at the University of Wisconsin’s Center for the History of Digital and Print Culture, “BH and DH: Book History and Digital Humanities.” It was a great gathering of people who live at the same intersection I’ve been stomping around.

And it gave me a chance to think again about digital facsimiles of early printed books. As I said in my talk, book historians think about digital facsimiles mostly in terms of what they show (“hey, cool book! why is it using that funky typeface?”). But what if book historians were to ask BH questions of digital facsimiles—what if we were to treat them as objects to be studies instead of (transparent) objects of objects to be studied?

Because I was part of a very fun roundtable, I could mostly ask questions and not insist on answers (best format ever). So here, without answers, is the digital facsimile I chose (only partially at random) to ask questions of:

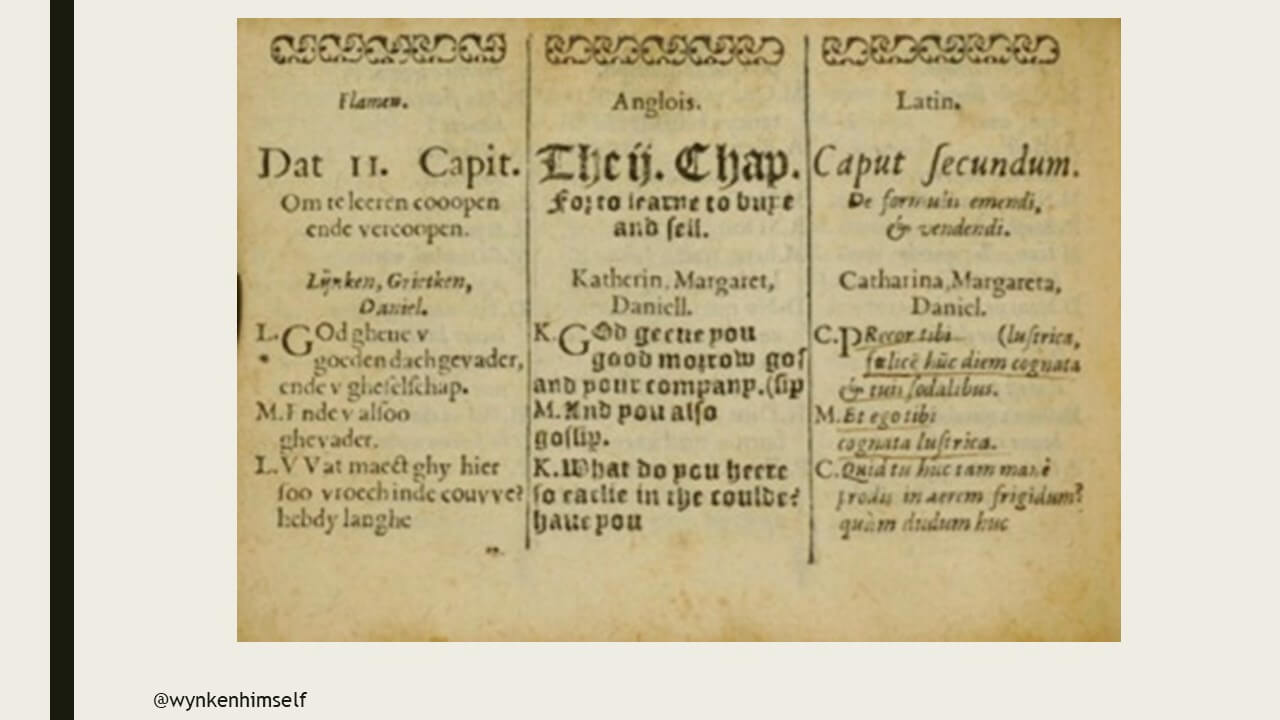

It’s hard to resist diving right into that awesome book, I know. But resist we must, so that we can see the object for what it is. And what is it? (I’m sorry for the images of slides; I’m trying to be fast so I don’t have blogger’s panic.)

Well, it’s a picture of a printed page. Do we know anything else? We can probably go so far as to say it’s a jpeg. But another way of asking “what is it?” is to ask, “what is shown and not shown?” And that’s easier to answer. It doesn’t show anything that doesn’t interfere with the text. It’s a flat single page that leaves out any signals about where it might be in a book (is it recto or verso? towards the front or back of the volume?).

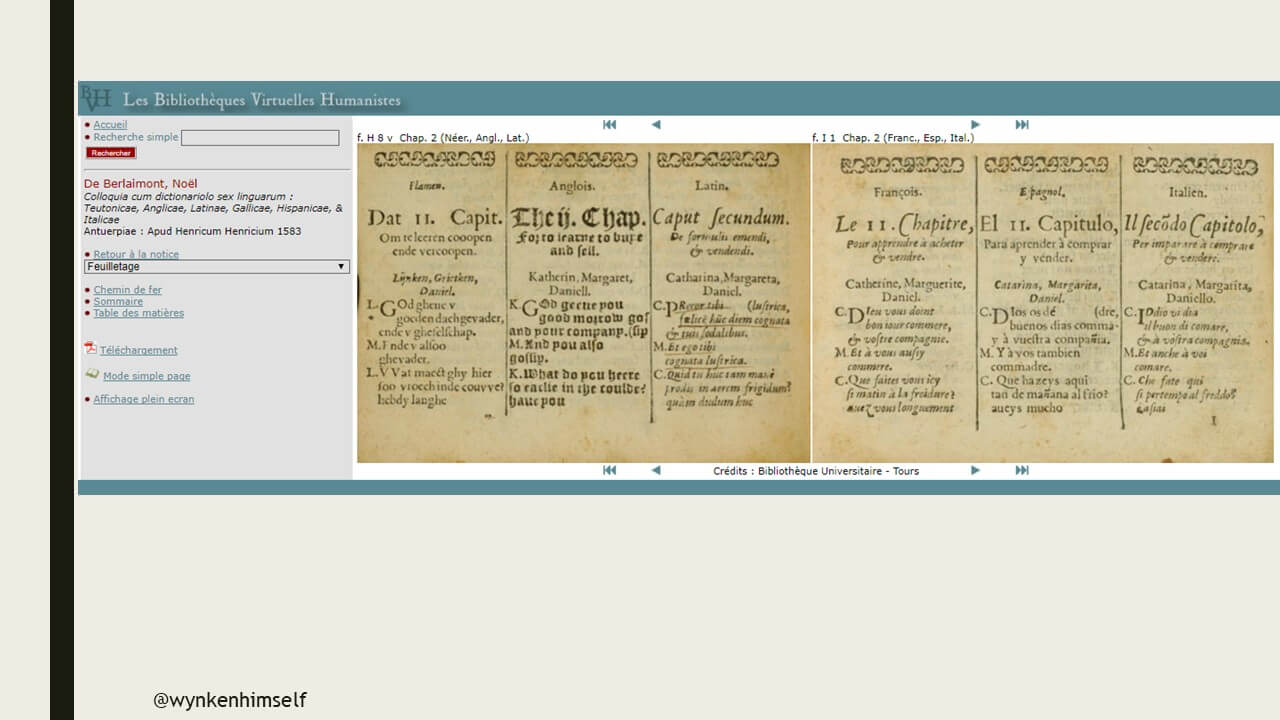

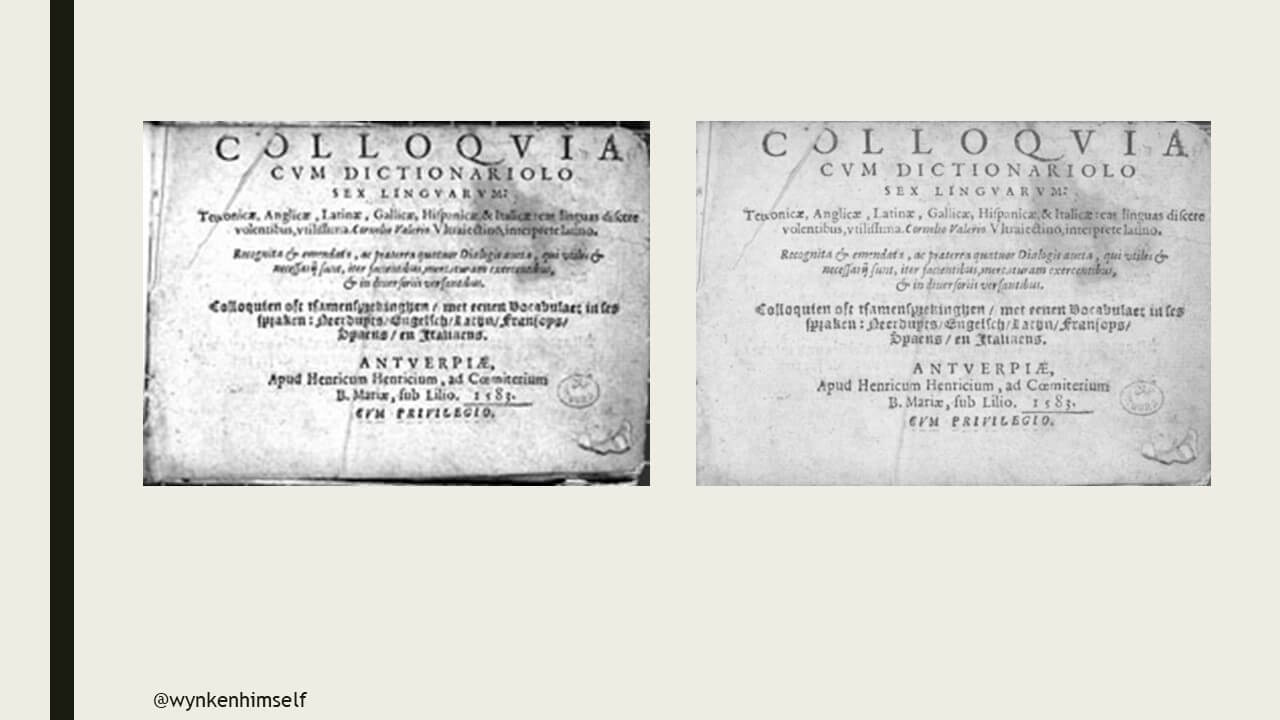

In the context of its platform, you can tell a lot more about what it is:

This is an image of the verso of the 8th leaf in the H gathering of a 1583 Antwerp edition of Noel de Berlaimont’s Colloquies. Seeing it in this context lets us make another assertion about this digital object: it’s an image that is meant to be seen in this viewer; this is the platform that provides information about what the picture depicts and how to navigate to related images. (Here’s the link to this view so you can play with it yourselves.)

Another question I think a book historian would ask is who made this image (we’re super focused on printers and publishers, right?). And although the image itself provides no clues about this, the platform does tell us that the image is provided by Les Bibliothèques Virtuelles Humanistes, a project at Centre d’Études Supérieures de la Renaissance at the Université François-Rabelais Tours, of the copy held at the Bibliothèque Universitaire.

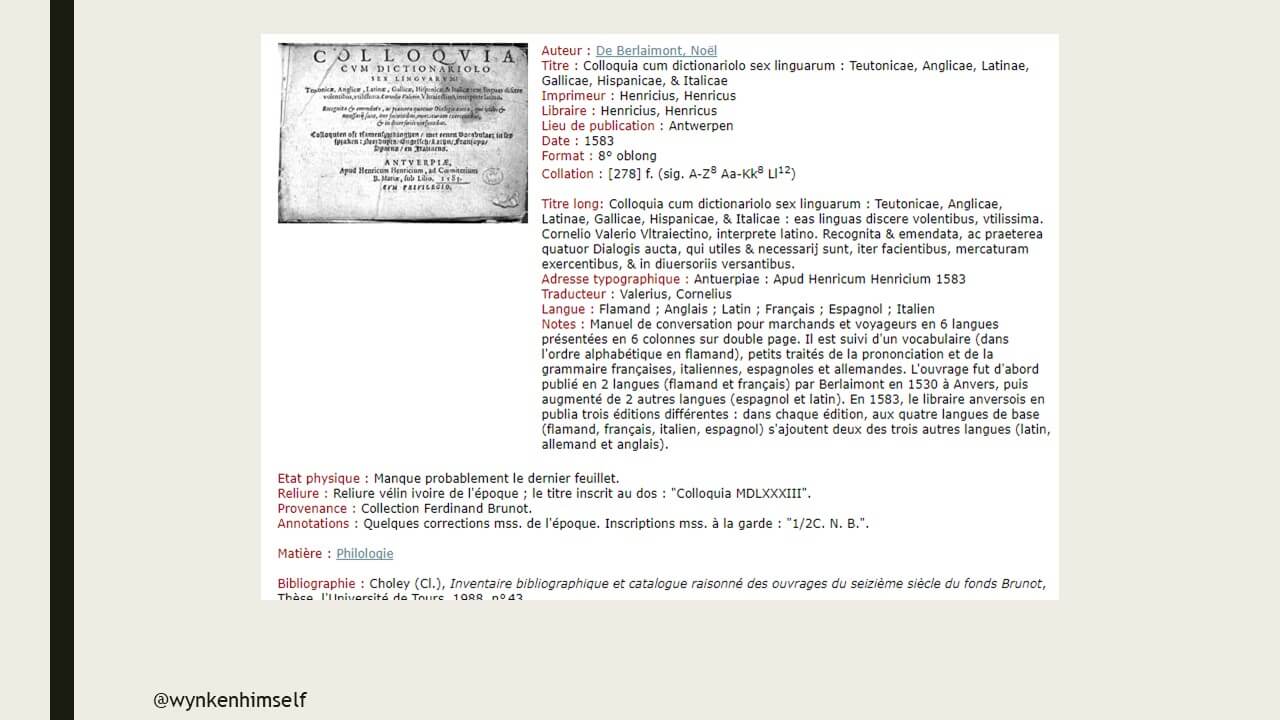

But who imaged this? To use book history equivalents, BVH is the publisher, but who are the printers? For that we can follow the platform link to the catalog record . . .

. . . where we get a lot more information about the object imaged, and if we scroll down . . .

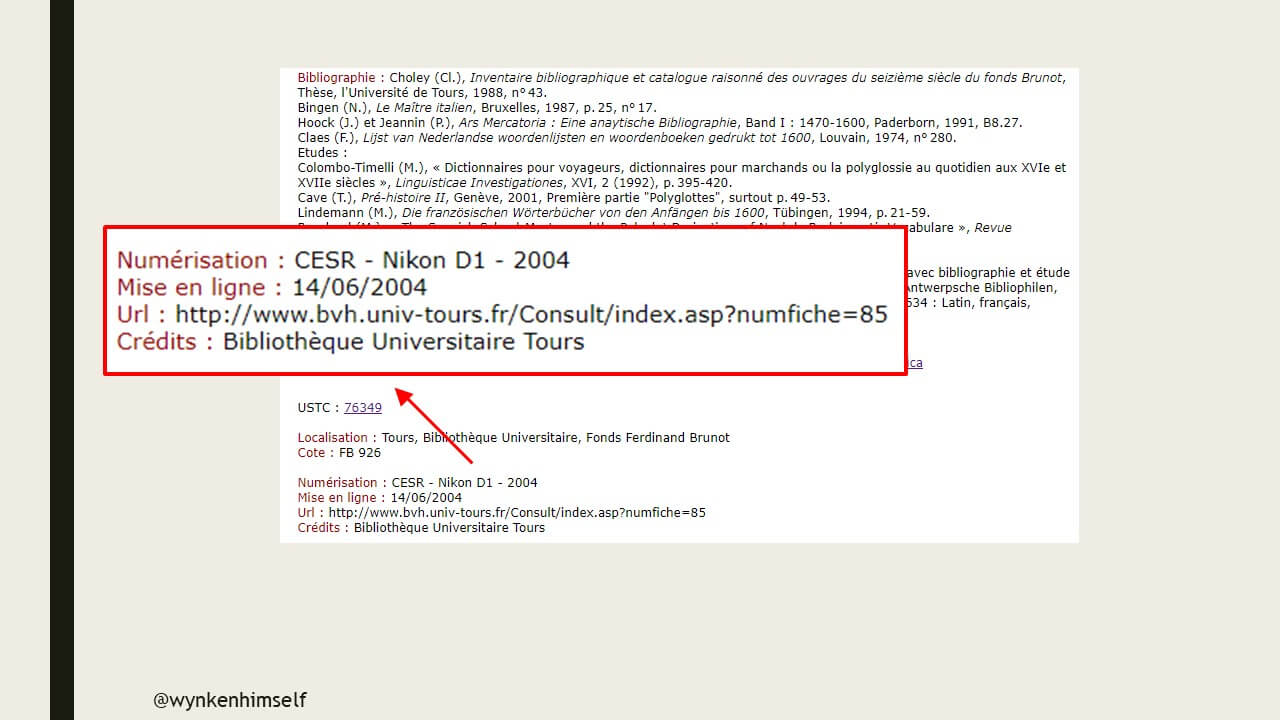

. . . we can find some basic points about what equipment was used, when it was digitized, and when it was put online. It’s not much (there are no names and no information about software or post-processing), but it’s way more than is usually provided on digital platforms.

BUT!

Did you notice that image of the title page at the top of the catalog record? Did it strike you at all?

Yep. The image in the catalog is grey-scale and the image in the platform is color. So, what’s that thing in the record?

I suspect it’s a grey-scale version of the color image. I did a super quick tweak and with a bit more effort, it wouldn’t be hard to get that color image to look like the grey-scale one.

But that doesn’t really answer the question of what’s going on here. Why? Why is the image in the catalog grey instead of color? I always tell my bibliography students that if you see something funky happening in your book, it’s a sign something happened in the manufacturing process that should be investigated. The same holds true here: what’s going on?

Well, I don’t know. Without writing to the folks responsible for building the catalog, I can’t tell (and who knows if they’re even still on staff there or if they left notes about their working and decision-making processes). I could guess that maybe it seemed like using grey-scale images would lessen the drain on the resources supporting the catalog (smaller image files, faster loading time).

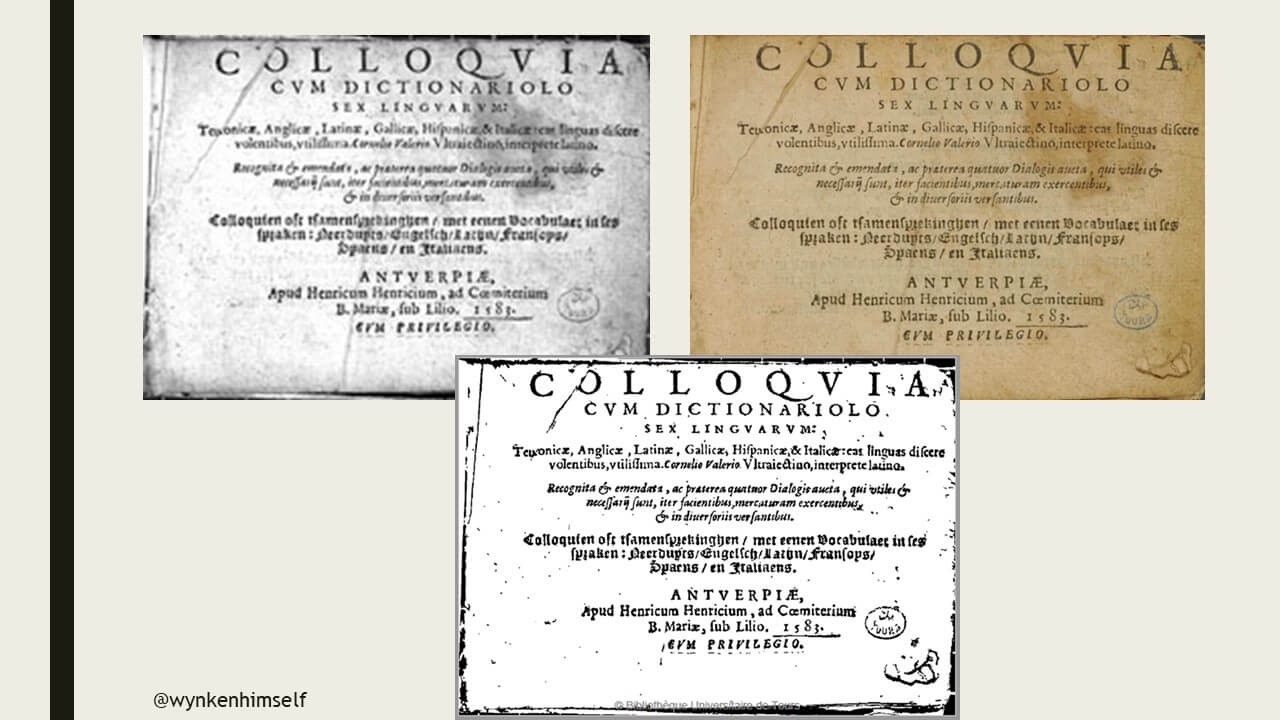

But we’re not done with the weirdness yet!

On the right is what you get when you download the full set of images (this is from the option “format pdf binaire haute définition pour l’impression”). It’s not color, or grey-scale. To my EEBO-trained eyes, it looks an awful lot like digitized microfilm.

Initially, that’s what I thought it was, but then I saw that even the objects imaged in 2016 were also available to download in this weird black-and-white option. It’s possible that their entire library was microfilmed and they’re only now getting around to doing color imaging. But that doesn’t quite explain why they’ve left these horrible-to-read images as high-resolution options. (Check out the 2016 digitization of this manuscript letter and the pdf download option; that’s no fun to read.)

So now I think we’re back to asking what is this thing and how many editions or impressions are there of it? What’s the relationship between these different iterations? How are they used, why were they produced, what does their production and usage say about the values or intentions or economics of the folks that produced them and of the systems in which they circulate?

These are book history questions, even if these aren’t books.

ps: Hi, folks! It’s been a while. I’ve been busy writing writing writing, and the good news is that my book is finished and in the hands of the publisher and should be available to be in your hands this coming spring. Oh, right: it’s called Studying Early Printed Books 1450-1800: A Practical Guide. It does exactly what the title says—it will teach you how such books were made, how to understand the signs of their making, what interpretations we can draw from all of that, and how to work with books in person or online. I suppose it could’ve been called Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Early Printed Books But Were Afraid To Ask, but it’s not. In any case, I’ve been busy and all my writing energies have been directed elsewhere. And now I’m focused on building a website, Early Printed Books, as a companion to the book, and so even though I like to think I’ll be writing more here, I might not be. Fingers crossed, but don’t forget you can always find me on twitter (@wynkenhimself but you probably know that).

One thought on “book history questions and digital facsimiles”

Comments are closed.