It’s that time of year again: another semester and more learning and teaching to be done! In honor, once again, of all of us involved in those activities, here’s a look another book that will help us “learn to be wise.”

Last fall, the book with which I started off the semester was a copy of Lily’s Grammar, the standard Latin textbook of the period. I’m not sure if that book will exactly help you to be wise, although it was certainly used to help you master your early modern Latin. This time, the book I’m focusing on is Johann Comenius’s Orbis sensualium pictus, or, A World of Things Obvious to the Senses Drawn in Pictures. Comenius’s book, first published in 1658 in Latin and German, is often described as the first children’s picture book. His intent was to teach children not only how to read, but how to be wise. That wasn’t an unusual aim for the time. What was new was his method: using pictures of worldly activities and objects to engage his young readers.

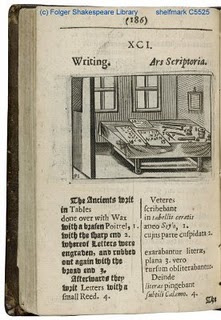

Last time I mentioned Comenius, I used his illustration of a scholar at his study to start off my post. Above is the illustration for writing: a table laid out with the implements for and examples of different kinds of writing. On the right side are the various instruments, keyed by numbers in the text to the details in the illustration:

The Ancients writ in Tables done over with Wax with a brasen Poitrel, 1. with the sharp end 2. whereof Letters were engraven, and rubbed out again with the broad end 3.Afterwards they writ Letters with a small Reed. 4.

As you can see from the picture below, the book uses shifts between blackletter, roman, and italic fonts to differentiate between those things illustrated and between the different languages. (My italics are a small attempt to transcribe the shift between blackletter and roman.)

The text continues on the next page to describe how “we” write today:

We use a Goos-quill, 5. the Stem 6. of which we make with a Pen-kife; 7. then we dip the neb in an Ink-horn, 8. which is stopped with a Stopple, 9. and we put our Pens into a Pennar. 10.We dry a writing with Blotting-paper, or Calis-sand, out of a Sand-box, 11.And we indeed, write from the left hand, towards the right; 12. the Hebrews from the right-hand towards the left; 13. the Chinois, and other Indians, from the top downwards. 14.

One of the fun things about this book for me is the descriptions of activities related to book history–there are pages not only for the scholar and for writing, but for paper, printing, the book-seller’s shop, the book-binder, and even for a book. I don’t have images for all of those, but on Google Books you can find the 1887 edition of Orbis pictus, which reuses the 1658 illustrations.

Comenius’s impact on children’s education and book history is huge. His method for engaging children through pictures and narratives about the world around us not only made his book tremendously popular, it has shaped nearly all such books since. His method is wholly familiar to us today–it’s how we routinely teach our kids to read. In fact, what Orbis pictus reminds me most strongly of is Richard Scarry’s stories about Busytown. And let me tell you, as someone whose children love my old copies of Richard Scarry, wow is that a book that appeals to little kids! (You can see a few images from Busy, Busy Town and What Do People Do All Day? on Amazon.)

Comenius’s Orbis pictus starts off with a dialogue between The Master and a Boy which lays out concisely the purpose not only of his book, but of all subsequent children’s books:

M. Come Boy learn to be wise.P. What doth this mean, To be wise.M. To understand rightly, to do rightly, and to speak out rightly, all that are necessary.

Comenius’s book is organized not only around A World of Things Obvious to the Senses–or what people do all day–but in an order that makes sense of that world rightly. The book moves from God then the World through all the worldly activities and objects until we reach Gods Providence and the last Judgment.

Naming the world around us to children always means embedding that world in our moral structure, from where we begin and end our narrative to how we describe the activities that take place in the world. It’s one of the qualities that can make children’s books so rewarding to study. Richard Scarry’s steady popularity makes it possible to trace the ways in which children’s books like these reflect our societal worldview–see this great Flickr set for some images comparing the 1963 and 1991 editions of The Best Word Book Ever. Given that my kids read my childhood Richard Scarry, we still name the handsome pilot and pretty stewardess. But I’ve never noticed the screaming lady–something to look forward to the next time my little one drags it out!