This is the time of year when I often feel assaulted by information overload: there are new books and articles being published in both of my fields of research, I’m behind on my New Yorker, novels are piling up by my bedside, and then don’t forget all those blogs and websites to check in with! Sitting down and constructing my syllabus exacerbates all this. There are too many new works to read that I might want to include, and even worse, I can’t always remember where I read that fascinating study that absolutely needs to be included. Didn’t I read something in that gigantic book that will help us understand the mise-en-page of printed Bibles? But where? And has it been eclipsed by something more recent that I haven’t gotten to yet?

Information overload. It often comes up as the bane of the electronice age, something that the email cockroaches and the endless web sites have unleashed on us. But Ann Blair argues that it is characteristic of the early modern world too.* The printing press was worried to have unleashed an overabundance of books, so many that they threatened to bury any useful knowledge in the sea of text. In response, early modern readers developed a host of reading and note-taking strategies to manage their information overload.

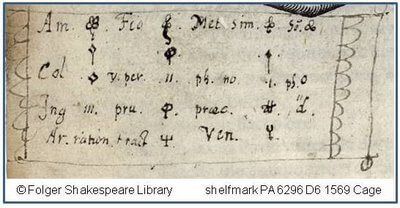

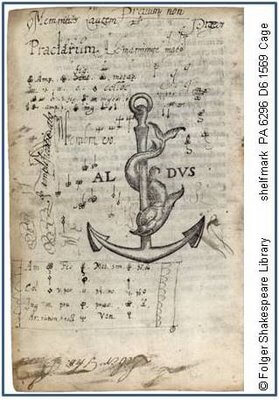

I’ve mentioned before the period’s prediliction for commonplacing. But how do you commonplace when there are too many books and too little time? Marginal annotation is one way: noting in the margin particular passages that you might want to return to later. But how to write in the margins quickly? Abbreviations are good: n.b. for nota bene, for instance. Developing a set of marks, each with a different meaning keyed to different categories of information or response is another. In the book pictured below, an early modern user has written a key to their marginal notations just below the printer’s device on the last leaf:

This particular book is a copy of Cicero’s De oratore printed by the Aldine Press in 1569. There are actually two keys on the last page (the picture at the top of the blog shows the one below the device; there is a second key above the device as well). The two keys differ slightly, and some of the symbols do not appear in the De oratore, which might suggest that the reader was developing a notation system during the course of reading the book. Bill Sherman notes that “a trident was used for passages of augmentation or reasoning and the symbol for Venus signalled an interest in love.”** Other symbols denote particular rhetorical devices.

Do we have a handy strategy for managing the information overload of the digital age? Google has tried hard to provide them for us. They’ve developed an appliance for searching effectively through an entire company’s files, and unveiled it in the appropriately titled blog, “Tackling information overload, 10 million documents at a time.” On a personal level, and one that connects directly with Renaissance reading strategies, is their Google Notebook. From their faq:

With Google Notebook, you can browse, clip, and organize information from across the web in a single online location that’s accessible from any computer. Planning a trip? Researching a product? Just add clippings to your notebook. You won’t ever have to leave your browser window.

It’s commonplacing! Although I have to point out that I find their last sentence a bit troubling: “you won’t ever have to leave your browser window.” Doesn’t it seem to suggest that you don’t even need to go on that trip that you’ve been research and clipping? Just more evidence that Google runs our lives.

*Ann Blair, “Reading Strategies for Coping with Information Overload ca. 1550-1700,” Journal of the History of Ideas 64 (2003): 11-28. Online via JSTOR for those of you with access.

**William H. Sherman, “‘Rather soiled by use’: Renaissance Readers and Modern Collectors” in The Reader Revealed, ed. Sabrina Alcorn Baron (Washington, DC: Folger Shakespeare Library, 2001), pp 84-01. This essay was originally written for the catalog of a Folger exhibition; an expanded version of this piece is in his most recent book, Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England (Philadelphia: U Pennsylvania P, 2008).